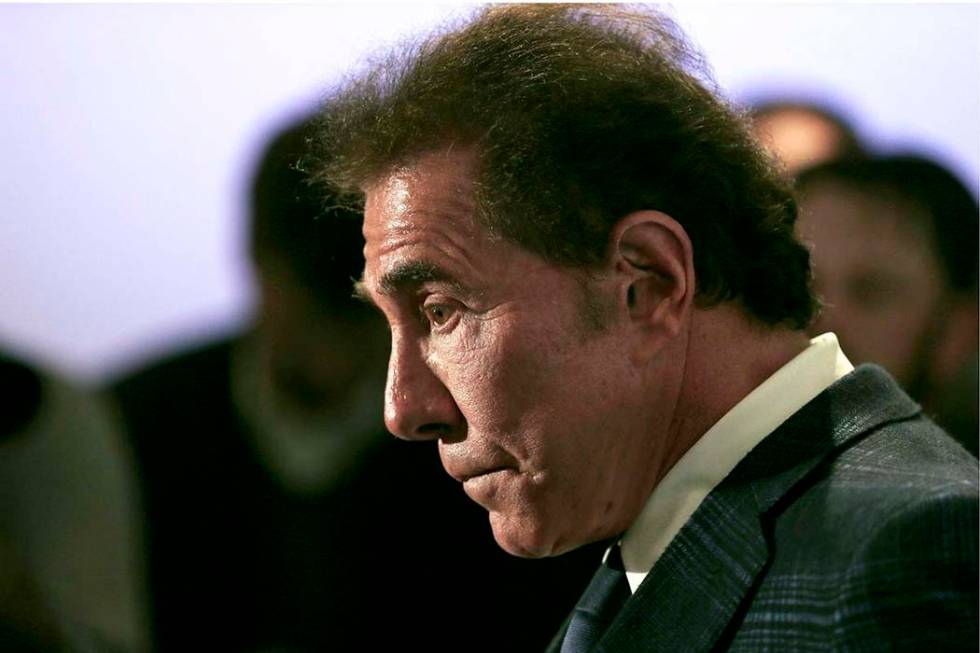

Nevada regulators in uncharted waters in Steve Wynn suitability case

It could take months for regulators to determine Steve Wynn’s suitability to continue to hold a gaming license in the wake of a complaint filed Monday.

State gaming regulators are in uncharted territory, testing areas of regulation they’ve never used before as they consider whether Wynn, the man credited with helping to reinvent Las Vegas in the 1980s and ’90s, should be stripped of his license.

Experts who have studied the city’s history say there’s really no precedent to the downward spiral Wynn’s case has taken. They’ve noted some comparisons with other leaders in the city’s past, but nothing like this.

“It really is unprecedented that somebody at that level with that history in the industry, having that outcome,” said David Schwartz, former director of UNLV’s Center for Gaming Research, who has written extensively on the casino industry and its history.

Wynn, 77, the former chairman and CEO of Wynn Resorts Ltd., was accused by the state Gaming Control Board of harassing multiple female employees for years. The five-count complaint signed by Board Chairwoman Sandra Morgan and members Terry Johnson and Philip Katsaros was delivered after the completion of a seven-month investigation that included interviews with victims, reviews of lawsuits filed against Wynn and the examination of 300 news articles about Wynn and his alleged harassment.

Telephone calls to Wynn’s attorney were not returned Tuesday. Wynn has repeatedly denied ever harassing anyone.

Statutes explain process

Nevada Revised Statutes and the Control Board’s Regulation 7 govern the procedure for disciplinary hearings for gaming licensees.

While the process is relatively clear, what’s unclear is Wynn’s status as a licensee subject to disciplinary action. Regulators say he is; Wynn says he isn’t.

Statutes say a complaint must be a “written statement of charges which must set forth in ordinary and concise language the acts or omissions with which the respondent is charged.” It also must say which statutes or regulations were violated and the complaint does that.

Once a complaint is filed, the commission is required to serve a copy personally or through registered or certified mail to the respondent.

Within 20 days — by around Nov. 3 — the respondent must state in short and plain terms the defenses to each claim asserted, must admit or deny the facts alleged in the complaint and must state which allegations the respondent doesn’t know about.

The regulation says those allegations are deemed denied. Regulations say failure to demand a hearing constitutes a waiver of the right to a hearing and to judicial review of any decision or order of the commission, but the commission may order a hearing even if the respondent waives the right.

If a respondent doesn’t show up for a hearing, it’s considered an admission of all facts alleged in the complaint, and the board may take action on that admission.

But Wynn may have another option, and experts with knowledge of the process, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, disagree over whether it would happen.

One expert says Wynn has the right to judicial review, meaning he could petition a court for an injunction to put the brakes on any action.

That, in essence, is what Wynn did when the Massachusetts Gaming Commission was attempting to complete an investigation for an adjudicatory hearing to determine if Wynn Resorts was suitable for licensing prior to the opening of Encore Boston Harbor nearly a year ago.

Wynn’s actions temporarily blocked his former company’s ability to complete the hearing until weeks before the scheduled opening of the resort in suburban Boston.

Another expert says that strategy worked because Massachusetts law is different from Nevada’s, where an appeal to the court system can occur only after the board has rendered a decision. In Massachusetts, Wynn was able to escaped that commission’s discipline when it was determined that he was no longer a qualified licensee.

In Nevada, the Control Board determined Wynn was among 10 former Wynn Resorts employees who had their licenses placed on administrative hold, meaning they were still subject to regulatory scrutiny.

Wynn disputes that, based on his attorney’s comments to board investigators noted in the complaint. He offered to provide information to investigators in writing, but he refused to appear before them for an interview.

Not a ‘bona-fide licensee’

In the fifth count against Wynn, the complaint says “On Wednesday, Sept. 5, 2018, counsel for Mr. Wynn sent a letter to the Gaming Control Board claiming that Mr. Wynn was no longer a ‘bona-fide licensee’ and ‘remains willing to consider any and all written inquiries which will assist the (Gaming Control Board) in (its) investigation …’

“The letter further stated that because Mr. Wynn retained counsel with the intent to pursue defamation litigation related to the claims of Mr. Wynn’s unwelcome sexual conduct, Mr. Wynn ‘cannot be reasonably expected to waive any of his privileges except at the appropriate time and in the appropriate judicial forum,’ ” the complaint said.

The complaint noted that the Sept. 5, 2018, letter did not request Wynn’s excusal from an investigative hearing scheduled two days later. He failed to appear.

Investigators said they believed Wynn violated his company’s policies on sexual harassment and attempted to hide a $7.5 million settlement with one of his victims from the company’s board of directors.

Wynn Resorts was punished by both the Nevada Gaming Commission and the Massachusetts Gaming Commission with fines that totaled $55.5 million this year.

Steve Wynn stepped down as chairman and CEO in February 2018 and divested himself of all investment in the company a month later. If regulators revoked Wynn’s findings of suitability, he would effectively lose his license and likely would not be allowed to be licensed again in Nevada.

“Now, it’s in the hands of the commission, and I wouldn’t presume to know how they’re going to operate,” Schwartz said. “Certainly it would be a pretty momentous decision and a big statement either way.”

Michael Green, an associate professor in UNLV’s Department of History, said regulators have disciplined licensees in different ways over the years, but he can’t recall an executive of such high profile having his license revoked. He noted that Las Vegas philanthropist Ralph Engelstad was disciplined by the Nevada Gaming Commission in 1989 for bringing discredit to the state by staging birthday parties for Adolf Hitler. Commissioners fined Engelstad $1.5 million but didn’t revoke his license.

No ‘black book’ hearing

Green noted that Wynn isn’t being targeted as an addition to the state’s List of Excluded Persons, the so-called “black book,” because that’s generally reserved for mobsters and casino cheats.

“If you make that comparison, you have people who will tell you stories of the generosity of Engelstad and of Wynn,” Green said. “I looked at the current list of the ‘black book,’ and I thought about the last one and it’s not the same thing. You’re a mobster or you’re a cheater. That’s basically it. Those seem to be the only people they’ve determined to keep out. They have pulled some licenses over the years and some that they’ve told to get out or they would pull their license.”

Contact Richard N. Velotta at rvelotta@reviewjournal.com or 702-477-3893. Follow @RickVelotta on Twitter.