In Clark County, selling drugs that kill can lead to murder charges

Prosecutors desperate to stop the overdose deaths that have skyrocketed in Las Vegas in recent years have joined a national trend of charging drug dealers with murder.

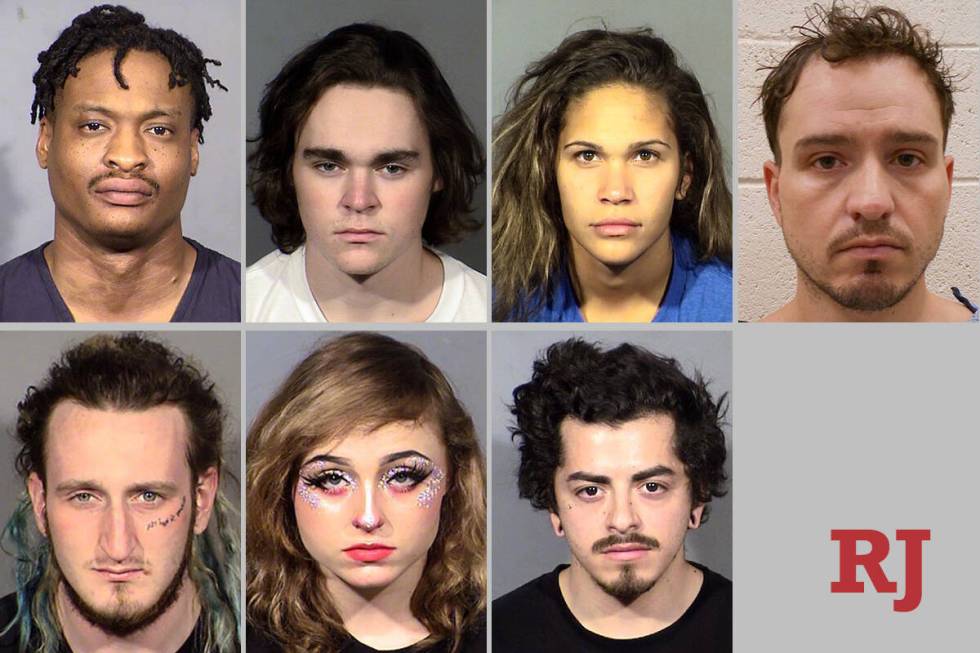

In the past two years, eight people have faced murder charges in Clark County after officials said they gave or sold drugs to someone who later died. Twenty other cases are currently under investigation, according to District Attorney Steve Wolfson.

The victims include a 21-year-old aspiring doctor, a teenage star athlete and an eighth-grade girl.

Lee Gugino’s 17-year-old daughter, Mia, died in February 2021 after police said a 22-year-old man gave her pills containing fentanyl, a synthetic opioid that has driven a dramatic increase in fatal overdoses.

“There needs to be drastic measures in all cases if we want to stop fentanyl,” Gugino said during a recent interview.

None of the eight recent cases has resulted in a murder conviction. Two people have pleaded guilty to a lesser charge of manslaughter, while the other cases are still being litigated.

Legal experts are skeptical that the alleged crimes amount to murder, or that prosecuting drug dealers will have a meaningful impact on the sheer number of fentanyl deaths.

“My job is to pursue these charges,” Wolfson told the Las Vegas Review-Journal in January. “The community wants these cases pursued.”

At least 218 people in Clark County died from a fentanyl overdose in 2021, according to data from the Clark County coroner’s office, although the toll could be higher as toxicology reports are finalized. Still, 2021 shows an increase from at least 181 people who died after overdosing on the drug in 2020, and more than three times the number of deaths from 2019, when 64 were recorded.

‘A big deterrent’

In light of the rising deaths, local law enforcement in July 2020 created an Overdose Response Team, made up of officials from the Metropolitan Police Department, Henderson Police Department, U.S. Department of Homeland Security and the Drug Enforcement Administration, according to internal Metro documents.

When determining if an overdose death will be investigated, the team considers whether it is linked to another death, and whether an “immediate action’ can be taken to identify the drug dealer, according to Metro records.

Metro Sgt. Kenneth Rios said he hopes the murder charges will alert parents, children and dealers to the dangers and consequences of selling opioids.

“The penalty being greater and the public knowing is a big deterrent,” Rios said.

In the 18 months after the team was created, those arrested include 21-year-old Aria Styron and 20-year-old Orianna Cervantes, who are each accused of supplying fentanyl-laced pills to a friend who later overdosed. Last month, prosecutors charged 32-year-old Marcas Crowley with murder after officials said he took and obtained explicit photos of a 13-year-old girl in exchange for the drugs that led to her fatal overdose.

“It’s time we stand up and take a stand for the parents … who have lost their children to this drug. And it’s time we take a stand for the people we represent,” said Tina Talim, one of the prosecutors focusing on overdose deaths, during the Jan. 27 sentencing hearing for Jayden Hughes.

Hughes, who pleaded guilty to involuntary manslaughter, has said he was asleep when his girlfriend smoked the residue from the three fentanyl pills he had consumed. She overdosed and died.

Jonathan Simon, a University of California, Berkeley professor of criminal justice, said that in many cases, it’s “virtually impossible” for investigators to tie the pills that caused a person’s death to a specific dealer.

“Can you prove the person you’re charging with the crime is really the cause of it?” he asked.

Wolfson said prosecutors don’t need to prove an intent to kill in order to bring second-degree murder charges.

Nevada law is vague on what qualifies as second-degree murder. While first-degree murder has multiple definitions under the law, including a “willful, deliberate and premeditated killing,” second-degree murder is only defined as “all other kinds of murder.”

In practice, second-degree charges are pursued when a killing happens during an unlawful act that “tends to destroy a human life,” said Eve Hanan, who teaches criminal law at UNLV.

In March 1983, the Nevada Supreme Court ruled that a drug dealer could be charged with murder in a fatal overdose if the dealer either helped someone take the drugs or was present when the drugs were consumed.

However, a bill approved in May 1983 specified that if someone sold drugs that caused the death of a minor, the seller was guilty of second-degree murder. The law was expanded in 1985 to include anyone who died, not just minors, and the statute currently indicates that the seller could be guilty of first- or second-degree murder.

As prosecutions increase, Hanan said, she’s worried that treating low-level dealers as murderers won’t stop the fentanyl crisis.

“We’re not really seeing prosecutions of drug lords, or people high up on the drug distribution chain, or manufacturers,” she said.

Other jurisdictions

Nevada is one of multiple states that have pursued the murder charges in recent years, with news reports of prosecutions in states including Florida, Georgia, Virginia and Colorado.

In California, Riverside County District Attorney Mike Hestrin said he was persuaded to view overdoses as homicides by the father of a 20-year-old woman who died in 2019 from a fentanyl-laced pill she took to help her sleep better.

“He opened my eyes to the victims’ perspective,” Hestrin told the Review-Journal. “He was asking me tough questions like, ‘Why isn’t this murder?’ It should be.”

Hestrin’s prosecutors have brought murder charges against 10 people, although like in Clark County, none has been convicted of murder.

Simon, the Berkeley law professor, said prosecutors across the country might be using the charges to create a buzz around fentanyl to deter dealers.

“I wish I believed that this would help,” he said. “I understand the pressure on district attorneys, both moral and their own sense of their role, and from voters. This has got to be one of the worst crises of our time.”

In Clark County, fatal overdose cases aren’t the first to involve murder charges in deaths not traditionally thought of as homicides. From 2017 to 2019, prosecutors began filing murder charges against defendants accused of deadly DUI crashes, until the Nevada Supreme Court in September 2020 issued a ruling banning the practice.

“Now, at the end of the day, if the Supreme Court tells us we can’t, so be it, and we will follow their directive,” Wolfson said of overdose murder cases. “But we’re confident that we are following the law and that we are doing the right thing.”

A star athlete

Lee Gugino said he didn’t know what fentanyl was until his daughter’s death.

The 17-year-old athlete and freshman at the College of Southern Nevada had injured her ACL while playing soccer a few months prior. After her surgery, she was given strong painkillers. That, combined with a recent breakup and the pressures from the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, led her down a path that ended with 22-year-old Joshua Roberts, her father said.

In the early hours of Feb. 19, Mia Gugino overdosed on pills that police said Roberts gave her, according to court records. During a January interview, Lee Gugino sat in his physical education classroom, which Mia helped him decorate at Tarr Elementary School, where she helped him coach the students. His voice shook when he recalled the morning he found her body.

“The only thing I could do was just cry and apologize,” he said. “I was supposed to keep her safe.”

Now that she’s gone, Lee Gugino comforts himself with home videos of Mia. In them she’s still smiling, telling the camera she’s about to beat the boys at a swim race or cheering after scoring a point in her lucky number 13 basketball jersey.

The parents of other teenagers who have died of overdoses reached out to Lee Gugino after Mia’s death, he said. Of all the cases, Lee Gugino said he doesn’t know why Mia’s death is being prosecuted, but he thinks it’s the right call.

“I mean, how much are we going to put up with this?” the father said. “We have a whole generation that’s dying.”

Contact Katelyn Newberg at knewberg@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0240. Follow @k_newberg on Twitter. Contact Sabrina Schnur at sschnur@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0278. Follow @sabrina_schnur on Twitter.