‘Somebody has to answer for this,’ says father of inmate who was strangled

Richard Dickman remembers exactly what the assistant sheriff said during the phone call about his son’s killing in a Las Vegas jail.

“He said, ‘We failed your son, and we failed you,’” said Richard Dickman, recalling the conversation he had with Metropolitan Police Department Assistant Sheriff Andrew Walsh in the aftermath of his son’s death.

For the 79-year-old former corrections officer, the perceived failure is personal. Dickman said security protocols he would have followed as a guard with the Nevada Department of Corrections were ignored the day his son, Jason, was placed in the Clark County Detention Center’s general population.

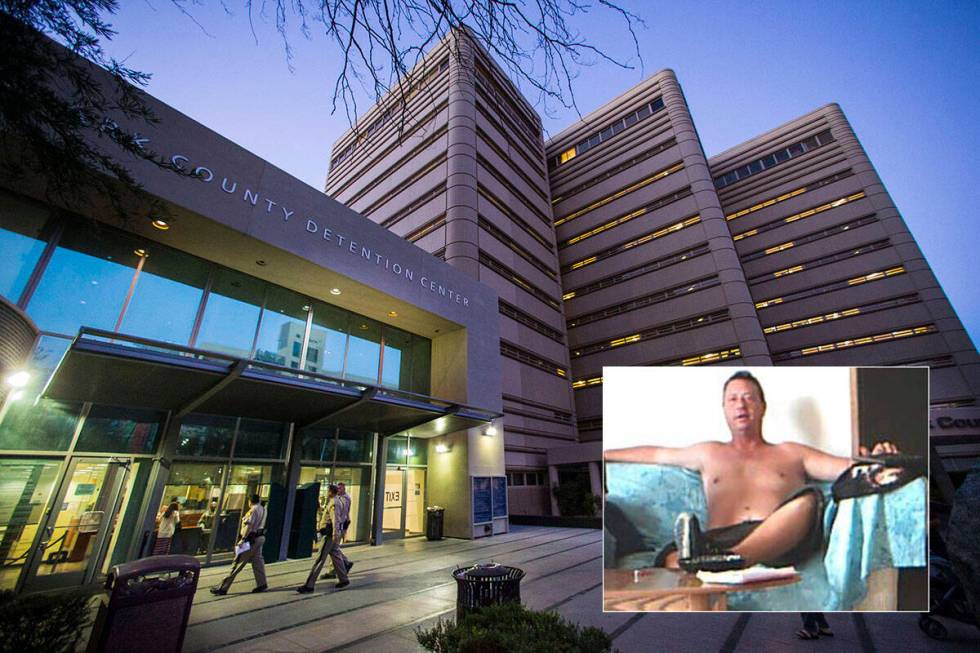

Jason Dickman, who was diagnosed with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, wasn’t separated into a unit meant for people with severe mental illnesses. Instead, he was placed in at least two general population cells with 41-year-old Sergio Dominguez.

About two minutes after walking into one of those cells the night of May 9, Dominguez ripped off his shirt and wrapped it around Jason Dickman’s neck, choking the 46-year-old to death, according to a federal lawsuit the victim’s father filed in December.

“Somebody has to answer for this, in some way, shape or form,” Richard Dickman said during a January phone interview. “And hopefully (the lawsuit) can stop it from happening to somebody else.”

He filed the wrongful death suit against Metro, which operates the jail; the corrections officer who responded to the attack; Clark County; and Wellpath, a private company in charge of medical care at the jail.

When sent a list of questions about the case, Metro declined to comment, citing the pending litigation. Clark County also declined to comment on the lawsuit, and Wellpath did not reply to a request for comment.

Richard Dickman’s lawyer, Peter Goldstein, said it’s jail policy to house severely mentally ill inmates in protective custody for their own safety. Jail staff should have known that Jason Dickman fit into the category, Goldstein wrote in the lawsuit, because he had been arrested about 20 times in recent years, mostly for minor charges like vandalism or failing to appear in court.

Jason Dickman was “obsessed” with graffiti and loved art, his father said. It was another graffiti violation that landed him in jail on May 8.

Dominguez was arrested the following day on burglary and arson charges. The two were placed in the same cell, and “a dispute or conflict arose” between the two men, the suit states.

Richard Dickman said that because of his son’s schizophrenia, it’s possible he said something to offend the other man. But he still doesn’t know what the dispute was about.

Homicide due to strangulation

During an interview with police, Dominguez said he “never had an exchange of words” with Jason Dickman, and expressed no remorse for the attack, according to testimony from a homicide detective during a grand jury hearing in June.

Later that evening, Jason Dickman again was moved into another cell with Dominguez, court records show.

For unknown reasons, at about 8:10 p.m. Jason Dickman pushed a call button used to draw the attention of corrections officers, then went to use the cell’s urinal. Within a minute of the button being pushed, Dominguez walked up behind Jason Dickman and started choking him, according to court transcripts.

Early in the attack, Jason Dickman managed to crawl to the call button and press it again, while Dominguez hung from his back, “wrenching” the shirt around his neck, the detective told the grand jury.

At about 8:19 p.m., a corrections officer identified as “J. Neville” notified his sergeant that Jason Dickman was being attacked, according to the lawsuit.

“When officers finally arrived to restrain Dominguez, he was still on top of Jason, who was covered in his own vomit,” Goldstein wrote in the suit.

Jason Dickman was pronounced dead at University Medical Center at 8:54 p.m., according to the suit. The Clark County coroner’s office has ruled his death a homicide due to strangulation, and Dominguez now faces a murder charge.

The lawsuit argues that Wellpath, which is based out of Tennessee and operates in facilities in 37 states, has a history of providing inadequate medical and mental health care.

In December 2018, the Department of Justice opened an investigation into the Hampton Roads Regional Jail in Virginia, and found that Wellpath employees failed to properly screen prisoners with mental illnesses and kept “inadequate and inaccurate” records,” Goldstein wrote in the lawsuit.

Wellpath took over medical care for Clark County Detention Center inmates in 2019, “despite Wellpath’s sordid and well-publicized reputation for providing constitutionally inadequate care,” Goldstein wrote. Clark County pays the company at least $23.8 million annually for its services, according to the lawsuit.

‘No one should die in jail’

Richard Dickman thought his son would be safer in Nevada.

Las Vegas is where his son grew up, playing football as a child and wrestling in high school. He loved hanging out at his father’s skateboard shop, which Richard Dickman opened after retiring in about 1989 from the Division of Parole and Probation, a job he held after spending time as an officer with the Department of Corrections in the 1970s.

When Jason Dickman was older, the two moved to Florida to take care of his mother. But his father sent him back to Las Vegas after the woman’s death, because Richard Dickman thought the mental health care system in the area would be more beneficial for his son.

Richard Dickman kept worrying as his son’s mental health declined, but he still received regular phone calls. He had to remind his son that his mother was dead, but at least the father could still hear his son’s voice.

It was May 10, after weeks without a call, when Richard Dickman learned of his son’s death. It was Jason Dickman’s case worker who had figured it out, after seeing on the news that an inmate had been killed. The case worker was the first person to tell Richard Dickman, not anyone from Metro.

The conversation with the assistant sheriff came after Richard Dickman wrote a letter to Sheriff Joe Lombardo. He appreciated that Walsh opened up to him, but he still can’t reconcile what happened to his son with the training he went through when he was a corrections officer.

If he had been on duty when an inmate was attacked, Richard Dickman said, he would have done anything to stop it. What really bothered him was the reaction of a homicide detective Richard Dickman said he talked to in the weeks after his son’s death.

“‘Bad guys do bad things’ — that’s what he said to me,” the father recalled. “… I said, ‘Well, nobody should die in jail, sir.’”

Contact Katelyn Newberg at knewberg@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0240. Follow @k_newberg on Twitter.