Famed DJ seeks a home for African-American artifacts

He’s a Negro.

That’s the word — and the era — he embraces, the racial ID of his generation’s America.

Yet he knows more than most about every painful stage of this nation’s roiling racial history.

And his startling subterranean lair — a walk-through of living, breathing African-American history — proves that. Spanning centuries with a massive array of artifacts that likely would leave historians breathless, it tells the story of the black experience in America more than days of lectures during Black History Month ever could.

He knows that history from the days when average Americans used the "N" word to describe their property, to today, when decent ones don’t use it to describe their fellow human beings.

He’s comfortable with where he falls on that racial timeline.

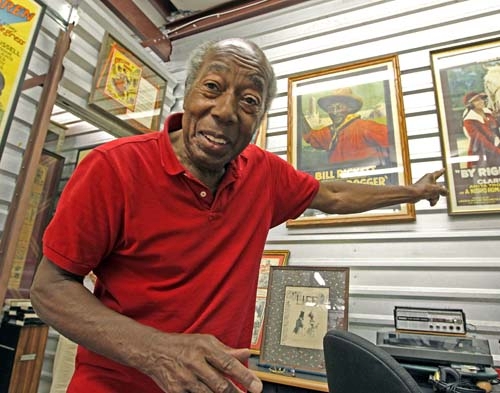

"The African-American is the civil rights black, he is not the Negro — I’m from the Negro side," says 83-year-old Nathaniel Montague, whose first name long ago morphed into "Magnificent." Yes, "Magnificent Montague" — a royal moniker for a man who earned fame for what he did before an audience, but has yet to receive it for an enormous gift he could give his people and a nation.

"I believe in the term ‘Negro,’ " he says, and much of what that means he learned from Jews. "They introduced me to what they knew about black, the Negro. They knew what I didn’t. I was asking questions I couldn’t get answered even by blacks, but they knew."

He’s Jewish now.

Decades past his racial naivete, he’s likely forgotten more African-American history than a university library of textbooks ever covered. He had the moxie to marry a white woman from Louisiana in Jim Crow America. You’ve heard of "Burn, baby, burn," the expression that fanned the intense flames of the 1965 Watts riots, rode atop the throbbing backbeat of "Disco Inferno" and even survived the Palin-esque distortion of "Drill, baby, drill"?

Came out of his mouth first, as a city’s racial fury found its voice in his words. On the radio. Where he made his bones — big-time — as an R&B record-spinning, love poem-spouting disc jockey from New York to Chicago to Houston to San Francisco to Los Angeles, while also assuming the roles of record producer and station owner.

Oh, and this collection of 6,000-plus rare, original artifacts dating back to slavery? The one that would be the envy of most museums and is, strangely, shoehorned into storage units on the west side of Las Vegas, its educational and cultural value ignored?

All his. Meticulously assembled and curated since the 1950s in a DJ’s spare time by scouring book and antique shops, garage sales and auctions, among other sources, it burgeoned into one of the largest private collections of African-American memorabilia in the world.

Large enough to draw the interest of the Smithsonian Institution, whose curators will arrive in Las Vegas next month to evaluate its contents and, perhaps, finally expose it to an unknowing public.

Admittedly, at Montague’s age, exhaustion does set in. Which is to say he can exhaust you.

"Come over here! Come over here! Look! Look at this!" says the fit, wiry octogenarian with the on-air voice time hasn’t weakened. The 13-year Las Vegas resident lifts a framed collection of old fliers billboarding 1926’s "Ebony Follies," featuring "The Big Brown-Skin Beauty Chorus."

Gesturing toward the only surviving recording of the voice of Booker T. Washington, recorded during an 1895 address to Atlanta’s Cotton States and International Exposition, Montague’s passion sprays out like 7-Up from a just-opened bottle.

"For years, the person who had it said, ‘No! No! No!’ " Montague remembers. "I begged. I cried over the years. I had to have it, to preserve it so it can be with me. Why? It became an obsession, like a drug. Finally, the person said, ‘It belongs with you.’ It cost me 10 arms and 10 legs. That’s how this collection began to mushroom."

History heaven: books, actual slave contracts, movie and minstrel posters, film, paintings, photos, period magazines, autographs, manuscripts, recordings, sheet music, letters, engravings, dolls, toys, racial comic strips and more.

And its worth?

"Anywhere between $50 million to $100 million in terms of what could be generated in sales," says Clinton Byrd, a financial services consultant retained by Montague. "I say that because of its potential with Amazon and Kindle and the downloading of books. What would a person pay for it? I think a venture capitalist looking at this, if they could get it for $10 million to $15 million, they’d feel they had a bargain."

Everything original. Nothing reproduced. The real deals.

"As an African-American going in to see the collection for the first time it brought tears to my eyes," says Marsha Irvin, retired chancellor of the Andre Agassi College Preparatory Academy in Las Vegas, which serves mostly African-American students.

"I have tremendous pride for what African-American women did in the 1700s and 1800s. Very inspiring for me was to hold Phillis Wheatley’s book of poems." Wheatley was the first published African-American poet.

Irvin continues: "It’s history you can touch, read, see and it’s breathtaking the way it’s been catalogued. To be a child being able to grow up knowing this history, it would’ve been tremendous. Just think of the attraction it could bring to Las Vegas. The only place in the world to have this."

How about anyplace else? No universities, companies or wealthy donors, African-American or otherwise, have yet rescued this remarkable, secret find.

All of it remains homeless, padlocked, untouchable.

THE MAKING OF MONTAGUE

"I want you to reach out, reach through your radio and just touch my heart. Burn my heart with desire. Ooh, yeah, yeah! I want you to call my name … I can’t hear ya, darlin.’ Have mercy on me … Free at last. I found my soul. I found my heart and your love."

— Montague’s theme song, recorded with Cissy Houston and Aretha Franklin

Born in 1928 and raised in segregated Elizabeth, N.J., the future Magnificent Montague was largely unschooled in racial animus. Call it what you will — isolated, ignorant, just unaware.

"I didn’t know anything about being a Negro, except I was one," he says. "I was raised in a home where we didn’t talk about color, we talked about religion. I was a kid. I didn’t know from nothing."

After attending a black military school, which led to a stint in the merchant marines during World War II, the lifelong radio junkie stepped off the boat in Galveston Bay in Texas to hear of a DJ vacancy at KTRM in nearby Beaumont.

That gig earned him a visit from the Ku Klux Klan, convinced he, of the husky pipes and entertaining delivery, was purposely seducing their white women. A fellow DJ named J.P. Richardson — later known as The Big Bopper — calmed the Klan by assuring them that wasn’t Montague’s purpose.

Following a brief stop at a Houston station, Montague landed back at Galveston Bay at KTLW, a station with a signal that pinballed around the Gulf of Mexico. KTLW’s coverage included, fatefully, Lafayette, La., where teenage girls called in requesting tunes. One was named Rose.

"He was so different," recalls his wife of 56 years, Rose Casalan, about meeting Montague through his radio shows. "He puts on a show with poetry and music and this voice, it just stood out over the music. And we were in a town where there wasn’t a lot of variety of music. You listened to a lot of Cajun on the radio."

Finally connecting face-to-face at a concert he emceed, the pair courted and — as an interracial couple in 1955 Louisiana — married.

In his autobiography, "Burn, Baby! Burn!", co-authored by former L.A. Times reporter/editor Bob Baker, Montague recalls the time.

"I told her we were going to Chicago, but I didn’t tell her what it would be like for a teenage white girl to be driving through Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi and Tennessee with a black man … that I could get killed just for being with her. I never got out of the car during the day. I’d drop her off at a coffee shop, let her get a hot meal, and then she’d bring a sandwich in a bag out for me. On the road, we’d find a motel — always waiting until after dark — and I’d pick a safe distance away from the manager’s unit and tell her to go get a room — for herself. Once she was inside the room, I’d hurry in to join her."

And the scenery on the road?

Montague writes: "We passed one billboard that said, ‘Run, N—–, Run. Don’t let the sun go down on you."

WHAT’S NOT IN THIS COLLECTION?

Harlem Dead-End Kids? Most viewers of a certain age know the rowdy gang of white movie goofballs. Yet here they are, the little-known Harlem version, promoted on a poster for the film, "Take My Life," starring "an all-colored star cast." Western? Try "Harlem on the Prairie." Chick flick? Perhaps it’s "By Right of Birth," subtitled "a Negro romance of laughter and tears," produced by the black-owned company, Lincoln Productions.

Hung on the storage unit walls, they lead around the corner into the historical wonderland Montague and his 74-year-old wife — who is his archivist — have put together as sort of a mini-museum. It is the strangest of exhibit spaces, revealed only to select visitors.

Study sheet music of the classic "Listen to the Mockingbird," composed by a black Philadelphia barber, Richard Milburn, but credited to a white woman, Alice Hawthorne. Behold boxed recordings of the Black Swan Record Company, the first owned by African-Americans.

"He’s got things nobody has ever seen," says Linda Scalzi, owner of the Dead Poet Book Store in Las Vegas. "I sold him first editions of black authors, ‘Uncle Tom’s Cabin,’ documents I’ve come across.

"My husband and I would go to library sales and Monty was always, ‘Got anything? Got anything for me?’ I’m still holding a book for him signed by Richard Wright. He’s got a very important collection."

Photos include Stepin Fetchit (aka Lincoln Theodore Monroe Andrew Perry), who became the first millionaire black actor while earning everlasting scorn for embodying African-American stereotypes. Speaking of which: a San Francisco Chronicle comic strip from 1912, "Sambo Goes to School at Last," is drawn in the grotesque caricature of the time.

"I collect it. I didn’t write it; I didn’t paint it. It is what it is," Montague says about items that are shameful in their treatment of African-Americans, but integral to their history. "A collector doesn’t collect that way. If you go to the Smithsonian, do you have to like everything you see?"

Elsewhere: a poster for "Hilson’s Famous Minstrels." A blackface arcade game. A rusted, 1930s plaque from Amelia Island, Fla. for the "Negro Ocean Playground," a haven from white-only beaches. A rare painting by George Washington Carver.

"Pretty amazing, huh?" says Jim Olson, ex-chief of exhibits at the Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History. "When they asked me to look at the exhibit, what surprised me was the depth of it. With Montague’s collection, there are literally thousands of stories to tell. Those poetry readings, they’re so similar to rap music that it’s stunning."

Olson also marvels at the collection’s condition: "You’ve got a couple of amateur people who have become professional curators. They use acid-free paper, acid-free boxes, it’s the way things are packed, they’re looking out for the longevity of this stuff."

BURN, BABY, BURN

Climbing the dial, the determined DJ finally rocketed to radio’s stratosphere, making it to New York in the early 1960s on Long Island’s WWRL. After a stopover in Chicago, Montague’s move to L.A. in March 1965 — with his signature slogan — thrust him into a landmark chapter of urban unrest.

"I started ‘Burn, baby, burn!’ back in New York at WWRL," Montague says of the expression that revved up listeners for soul sizzlers from the likes of Wilson Pickett, his friend Sam Cooke and the early Motowners. (The phrase later became associated with African-American communist activist Bill Epton Jr., who was convicted of "criminal anarchy" after uttering the words during Harlem street protests that boiled over into violence in 1964.)

Merely five months after Montague settled in at L.A.’s KGFJ, in August 1965, the Watts neighborhood went up in flames in a six-day racial riot. It was triggered by a white police officer pulling over a young black man for alleged drunken driving, and left 34 people dead, 1,032 injured and 3,438 arrested in the city’s worst riot until the 1992 Rodney King incident set the city off again.

Very quickly, Montague had become a listener favorite. "Burn, baby, burn" leapt from an entertaining catchphrase to a rallying cry for protest, sparking destruction and violence.

"It drew attention to the segregation and what was happening on the South side. It gave the Negroes an opportunity to be heard," Montague says, seemingly ambivalent to this day over how his phrase was co-opted. "When they started looting and burning, the term was already there. My feeling was it had nothing to do with the situation, but it gave them recognition. They had a label."

Though defying initial pleas from station management to discontinue the phrase, Montague finally capitulated after a personal request from Mayor Sam Yorty, who called KGFJ, prompting Montague to switch reluctantly to "Have mercy, Los Angeles!" as his new signature.

"That ended the riots, they began to wane," his wife says. "(Listeners) had adopted him immediately. They had never heard a disc jockey like that before because he was a real showman on the radio. So when they started the fires, they took his handle."

Dropped or not, "Burn, baby, burn" and its permutations have survived as a part of the American lexicon, even set to music when The Trammps sang it to drive their 1976 hit, "Disco Inferno," from the "Saturday Night Live" soundtrack. Yet Montague still smarts from what he perceives as a lack of credit for its creation.

"’Burn, baby, burn’ has been used in every major category in the world, in sports, in music, even Sarah Palin turned it around," he says. "Nobody knows who coined that phrase, but I’m the man. I’ve thought about suing several times."

THE JEWISH COLLECTION CONNECTION

While Watts smoldered, the man whose words underlined one of the country’s worst racial riots was — Jewish. Converting in 1960, Montague had picked up the collecting passion and thirst for knowledge of his own heritage from Jewish book dealers who knew him from the radio.

"I got interested in the Jewish culture, the pride to know who they are, showing me what their problem was in America, how they were catching hell," Montague says.

"George Washington Carver, Booker T. Washington, I only knew about them because of my Jewish friends. White collectors were collecting more about the Negro than the Negro himself. That’s how I learned — not from the NAACP, not from the Negroes in the Urban League."

Collecting, he says, was a skill he had to develop: "I didn’t know how to collect. I spent a lot of time talking with dealers, meeting die-hard Jewish collectors. If there was a saucer, they collected it. If it was a pen, if it was Nazi or German, or rare books. When I learned how they did it I started looking for stuff, anything that had anything to say about the Negro I tried to buy — slavery, the whole thing.

"When I learned, I began to expand myself. I didn’t realize that (Thomas) Edison, they say he didn’t like blacks, but one of the first artists to record for him was a Negro — George W. Johnson, an ex-slave who sang ‘coon songs.’ He was the first black to cut a commercial recording."

How could he afford this expensive hobby? "I made a lot of money," he says simply. "I did good. I was one of the top-paid people and I write and publish songs and I owned singing groups." He also launched easy-listening KPLM in Palm Springs, Calif., now a successful country music station.

The result of his decades of dedication? A collection that leaves those who have seen it slack-jawed: Portraits of slaves caring for vegetable gardens, harvesting crops and doing laundry. A letter black general Toussaint L’ Ouverture wrote in 1800 before leading a revolution that liberated Haiti from the French. A book by a veteran of the black 54th regiment of Massachusetts, depicted in the movie "Glory."

And more. Way, way more, with historical documents and other memorabilia neatly stacked in rows and rows of boxes, awaiting display they will never get inside these storage walls.

"It changed my life and it should have an international audience, it’s too phenomenal to be in a warehouse," says financial consultant Byrd, who became aware of the collection while producing the African-American musical "Voices." Byrd first tried to interest his former employer, ARCO (Atlantic Richfield Company), to buy the exhibit, which Montague and his wife refuse to donate, given the time, money and passion they’ve invested.

"ARCO felt they were extended with their foundation resources," Byrd says. "I was trying to get Xerox to look at it also. I tried to get (radio personality) Tom Joyner and McDonald’s to take an interest, then Steve Jobs and Apple — they have such great potential for virtual museums. Then I made a connection with the George Foreman family, and we are seeing if George can open some doors for us."

Thus far, however, nada.

BLACK HISTORY DEGREES

The Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of African-American History is the first major museum to open on a website before completing a physical structure. It is slated to begin construction next year near the Washington Monument and open in 2015.

"They’re touring the country now, talking with different groups about preservation of history and looking for stuff to put in the collection — right now they have about 11,000 items and they’re trying to get 20,000 more," Byrd says.

"Two of their curators are coming here in July to take a look at the collection. Rose and Montague want to sell as much of the collection intact as possible, they don’t want to piece it out because it will lose value."

Appeals to the Association of African-American Museums are also planned. "We’re going to say, ‘Why don’t you do a collaborative effort to purchase this collection and then divide it up in different venues so people in different cities could get to see it?’" Byrd says. "Over five years, the collection would rotate to different locations."

Still waiting for a collection assembled with love to get a little love from benefactors, and physically and emotionally vital as he is, Montague is aware that time is ebbing away to realize his dream.

"I want it to be there for the masses, I want to stick with it until they bury me," he says. "My life is in there. I would hate to see this go somewhere and be broken up like a rummage sale. We had a lot of people interested but one guy said, ‘We just have to wait until you’re dead and we’ll get it.’ That’s a hell of a thing to say."

Though largely upbeat in his memoir, Montague writes in gloomier terms in the prologue about his prospects for breaking his collection out of its Las Vegas holding cell.

"I wanted to show … these gang members, these hip-hoppers, once they understood their history, there’d be no holding them back," he writes.

"I wanted to give them something more powerful than guns and turntables. I wanted to give them their B.H.D.s, their black history degrees. I wanted to show them how to soar like the black eagle. But we know not all dreams come true. I know I will not get there."

Next month … Smithsonian curators. … Searching for treasures … Likely to find them tucked into a generic Las Vegas storage joint.

That dream? Don’t burn it just yet, baby.

Contact reporter Steve Bornfeld at sbornfeld@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0256.