Stream of visitors shaped history of Pipe Spring

As the site of a reliable water source in an arid region, Arizona’s Pipe Spring has a long history.

First visited by nomads many centuries ago, the spring later attracted cliff-dwelling farmers, followed by the ancestors of the Kaibab Paiute people whose reservation surrounds Pipe Spring today. The Paiute way of life changed radically with the arrival of the Spanish explorers and a subsequent parade of traders, mountain men, soldiers, adventurers and Mormon settlers.

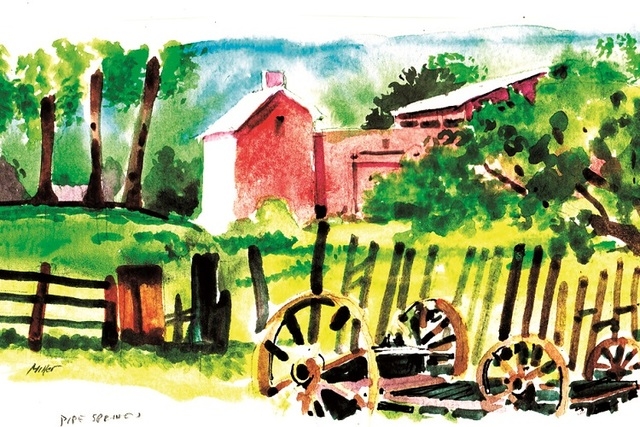

Pipe Spring was named a national monument in 1923 and today preserves a fortified pioneer ranch built in the 1870s.

It is about 185 miles from Las Vegas in northern Arizona near the Utah border. To reach Pipe Spring, drive north on Interstate 15 into Utah. Exit onto state Route 9 to Hurricane. In Hurricane, turn onto state Route 59, which becomes Arizona Route 389 at the state line. Drive east 45 miles to the national monument, located just north of the highway.

Pipe Spring provides an introduction to regional history during turbulent times. It was discovered in 1858 by Jacob Hamblin, a frontier guide, settler and missionary to the native people. The spring got its name from a shooting contest in which Hamblin’s brother William, a noted marksman, won a bet by shooting the bottom out of a man’s pipe at 50 paces.

Starting in 1854, native raiding parties from south of the Grand Canyon plagued the settlements and outlying ranches. In 1866, raiders drove off stock from a ranch that had been recently established at Pipe Spring and killed the two ranchers. Such raids forced some pioneers to leave their farms and small settlements and move to better-defended towns. By 1869, treaties had brought some peace to the frontier.

Located along a frontier trail, the spring became a stopover site for travelers, including leaders such as Brigham Young and explorers such as John Wesley Powell, who met there in 1870.

Young liked the location for its water, abundant grass and somewhat-cooler elevation at 5,000 feet. He tasked Anson Winsor with constructing a defensible ranch headquarters, and the two men paced off the shape of the project.

Winsor oversaw the construction of a two-story home built over the spring, using sandstone quarried nearby and timber cut and milled at Mount Turnbull 60 miles away. It was finished in 1872.

When Winsor’s wife and 10 children moved in, the building was informally called Winsor Castle. For years it served variously as headquarters for Mormon tithing herds, a farm, a dairy, a family home, a telegraph station, travelers’ lodgings, and a hideout for polygamous wives whose husbands were on the run from federal lawmen. The fortress never had to be defended.

Pipe Spring National Monument is open year-round, except Thanksgiving, Christmas and New Year’s Day. It offers a visitor center and bookshop with exhibits and an informative video. Titled “Encounter on the High Desert,” the film traces the historical interaction of the Paiutes, the Mormons and the U.S. government.

Entrance to Pipe Spring costs $5 for visitors older than 15. Free guided tours of the fort start each half-hour from early morning to late afternoon. The building is furnished with items typical of pioneer times. Visitors follow paved walkways to the garden, orchard, corrals and outbuildings. An unpaved trail to a ridge overlooks the historical site. Living history presentations are scheduled during the morning hours when visitors can see demonstrations of pioneer and Native American skills and crafts.

The high stone walls with heavy wooden doors at each end created a courtyard large enough to drive wagons inside. The families of a succession of ranch managers and guests were housed and fed in rooms on the north side. Rooms on the south side were work areas such as offices, the telegraph station and the dairy.

Natural geological forces pinched off the flow from Pipe Spring in 1999. The park service restored the flow with water from a neighboring spring.

Margo Bartlett Pesek’s Trip of the Week column appears on Sundays.