Humor in Depravity

It's tough enough getting local audiences to come to one theatrical event. But 10? And all within a three-week period? And all in some way "experimental"?

You have to label Ernest Hemmings, the organizer of the fifth annual Samuel Beckett Festival, as either smart visionary or deluxe nuts.

True, Beckett often is acknowledged as the granddaddy of minimalist playwrights -- his most famous work is probably "Waiting for Godot," in which two men simply wait under a tree for a man who never comes -- but he's also celebrated for his pessimism. And local theatergoers have a reputation for not liking dark thoughts.

But Hemmings is hopeful.

"I think Beckett is responsible for a lot of today's humor," he says. "He found humor in depravity, and I think a lot of TV shows and movies have tapped into that."

Peter Brook, writing in "The Empty Space," feels that Beckett isn't a pessimist at all. He argues that Beckett's philosophy is that man, despite being doomed to a meaningless existence, is an intrinsically optimistic creature.

"If you believe Beckett is pessimistic," Brook says, "then you are a Beckett character trapped in a Beckett play."

Beckett courted controversy all his life, up until his death in 1989, and the debate shows no signs of fading. It's likely you'll be hearing lots of argument in the hall between Theaters A and B on 1025 S. First St., where the festival, which opened Wednesday, is in progress.

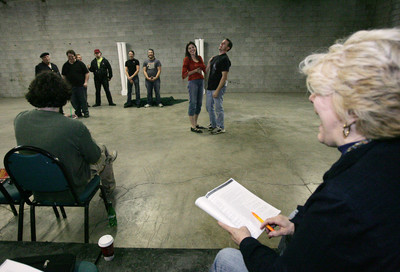

Hemmings, founder of Test Market Theater, talked several local troupes into participating.

"I think all of us are learning that things are a lot easier if we work together," he says. "The (emotional environment) in the theater community seems to be changing for the better."

Topping the attractions is "Happy Days," directed by Hemmings, about a woman buried up to her neck in mounds of earth. The play asks, what could she possibly see in life worth celebrating?

Robin Barcus and Jim Slonina, who are the founders of the newly formed LionHeart Theatrics, are tackling a mime piece called "Act Without Words (I and II)," because, Slonina says, "Beckett speaks to us." The first act is about a character struggling with unseen forces; the second features characters trying to work their way through daily, mundane tasks.

"I've always been interested in telling stories through physical expression, without the use of language," says Slonina, who performs in "Le Reve" at Wynn Las Vegas. "Act I's theme of isolation in a vast desert echoed pretty clearly my own plight in the months when I first arrived in Vegas."

Barcus, who has a background in visual arts, adds, "For me, what sealed the deal was the very first line of stage direction for Act Without Words I: 'Desert. Dazzling light.' I couldn't help but think this perfectly describes Las Vegas. I thought it would be a fun artistic challenge to place Beckett's work within the context of Sin City."

Barcus has some advice to those who find Beckett hard to follow. "Don't expect a traditional, realistic narrative," she says. "Look at his plays the way you might look at dreams. They may not take you from point A to point B in a logical manner, but nonetheless they present profound truths about human nature and society. ... What also saves Beckett is his humor."

Hemmings' program isn't sticking to just the master. He's surrounded Beckett with samples from other writers, performance artists and filmmakers whose works he feels are similar in temperament.

The Insurgo Movement's John Beane, for example, is mounting a difficult and seldom-seen masterpiece: Stanislaw Ignacy Witkiewicz's "The Water Hen." It features human and nonhuman creatures trying to create meaningful lives. Dead characters become undead, and little is what it seems in this metaphysical world.

Beane feels that "the theater lost something when it made the shift to realism. It lost the transportive quality that theater is capable of."

Part of Beane's job is to find some sort of logic within a world that some claim has none.

"The play's logic is its own," Beane says. "There is a trap in staging this kind of work -- the tendency to inflict a set of parameters of understanding on the events instead of just letting the characters exist. Existential pieces like 'Waiting for Godot' or 'No Exit' or 'The Water Hen' are fairly straightforward when done correctly," Beane says.

"That's the point," he continues. "Godot is -- really -- two guys waiting. 'No Exit' is three people discovering they are forced to be in a room forever. Trying to answer the unanswerable is what the plays are about for the characters, but not for the production. The production must concern itself with making these people live."

TJ Larsen, head of the new Found Door Theatre, says he felt an intimate relationship with John Patrick Shanley's "The Dreamer Examines His Pillow" as soon as he read it.

"The character of the father says a lot of things that make sense to me about art and love and sex and the choices we make in our lives," Larsen explains. "I think it's very romantic and funny with an edge that bites sometimes."

Larsen is one of four co-directors of Las Vegas Little Theatre's presentation of Neil LaBute's "Autobahn" which takes place entirely in the front seats of a car.

"One of the things I've always been drawn to in Beckett's plays is the sense of being thrown into something unprepared. The danger of a situation like that has always given my back hairs a quiver, and that is something I hope happens during 'Autobahn.' "

Hemmings is aware some of these plays demand a lot from an audience.

"It can be difficult because you are finding nuances that are not spelled out. The actor (and the audience) has to tap into it. Beckett (and the other plays) have an undercurrent. Not everything is spelled out."

What would Hemmings say to the guy who feels Beckett ultimately makes no sense?

"I'd say he hasn't seen good Beckett."

what: Samuel Beckett Festival

when: now through Dec. 15

where: 1025 S. First St.

tickets: $5 (opening-night performance)to $120 (pass to all shows); 736-4313 or www.thebeckett festival.com

THE PLAYS

"Act Without Words (I and II)" -- by Samuel Beckett, directed by LionHeart Theatrics' Robin Barcus and Jim Slonina. This mime explores the external and internal dimensions of man. Theater B: 8 p.m. Wednesday, Dec. 5, 12, and 14; 2 p.m. Dec. 8, 9 and 15.

"Autobahn" -- by Neil LaBute, directed by Las Vegas Little Theatre's Mark Brunton, TJ Larsen, Ela Rose and Courtney Sheets. A collection of one-act dramas. Theater B: 8 p.m. Saturday, Thursday, and Dec. 7 and 13.

Evolution Control Committee -- a comedy troupe from San Francisco that uses random sounds and media to form "dance-laden commentary." Theater B: 10 p.m. Dec. 1.

"Happy Days" -- by Samuel Beckett, directed by Test Market's Ernest Hemmings. A woman lives her life buried to the waist in sand. Theater B: 2 p.m. Saturday and Dec. 2; 8 p.m. Nov. 30, Dec. 6, 8, and 15.

Indiekrush.com -- short, absurdist films by locals Ron Riearson, Jordan Wright, and Jessica Yatrofsky, with live music . Theater B: 2 p.m. Dec. 1.

"Sum" -- by Ernest Hemmings, directed by Test Market's Hemmings. A man gambles that he could do a better job of raising himself than his father did. To prove it, he produces a clone. Theater B: 8 p.m. Friday, Dec. 1 and 7; 2 p.m. Sunday.

"The Dreamer Examines His Pillow" -- by John Patrick Shanley, directed by Found Door Theater's TJ Larsen. Three separate but related scenes delve into the relationship of three people who learn about love. Theater A: 2 p.m. Sunday; 8 p.m. today, Dec. 6, 8 and 15.

"The Water Hen" -- by Stanislaw Ignacy Witkiewicz, directed by John Beane of the Insurgo Movement. A water hen begs a man to shoot her, and when he does, the survivors (including the dead hen) embark on a metaphysical journey. Theater A: 2 p.m. Saturday; 8 p.m. Nov. 30, Dec. 2, 5, 12 and 13.

"Ventriloquist Sex" -- by Rick Mitchell, directed by Test Market's Ernest Hemmings. A ventriloquist aboard a cruise ship has a revolting dummy on his hands. Theater A: 8 p.m. Saturday, Thursday, Dec. 8 and 14; 2 p.m. Dec. 9

Wayward Ways Vaudeville Variety Show with Cheese and Pants -- The local Onyx Theatre comedy troupe teams up with a San Francisco outfit that combines surrealistic sounds and mime. Theater A: 8 p.m. Dec. 1.