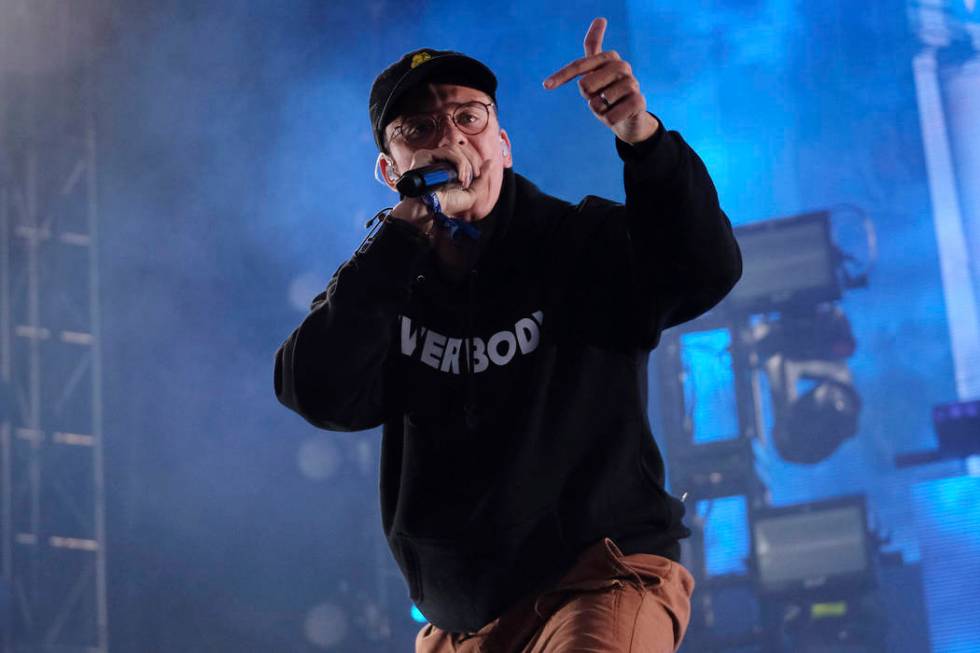

How Logic became one of hip-hop’s most unlikely stars

Logic defies logic upon occasion.

Sometimes, it’s audible, such as those moments when he rhymes so fast, you wonder if his tonsils get windburn.

In other instances, it’s less about his mic skills than his unlikely path to stardom. As in, how did this skinny, often bespectacled, generally unassuming 28-year-old who acknowledges that he’d rather spend time at GameStop than in the club become one of the biggest rappers around?

In the past year, Logic has released two No. 1 albums (2017 studio record “Everybody” and this year’s “Bobby Tarantino II” mixtape), graduated to headlining arenas and amphitheaters and turned in a much buzzed about performance at January’s Grammy Awards with an emotionally wrenching take on his suicide awareness song, “1-800-273-8255.”

His impact is being felt beyond the charts and packed concert halls: In the three weeks after the release of “1-800-273-8255,” which takes its name from the number of the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, the NSPL reported a 27 percent increase in calls and a 30 percent jump in visits to its website.

So what makes Logic, whose flow is a blend of Kendrick Lamar’s often-speedily-delivered social consciousness and Drake’s melodic lilt, a standout?

A quick primer:

He can hold his own with Chuck D and Black Thought

Public Enemy’s Chuck D and The Roots’ Black Thought are two of the greatest MCs of all time. To do your thing alongside those two is akin to throwing down with Nic Cage in a crazy-eyes contest: Most humans simply cannot compare.

Not only did Logic (Robert Hall) have the chutzpah to recruit both for a cut from “Everybody,” he somehow managed not to get lost in their skyscraper-sized shadows.

That song, “America,” is easily Hall’s most political tune, a throwback to Public Enemy’s late-’80s insurrectionist anthem “Fight the Power.”

Confronting what he sees as systemic racial inequality, Hall questions the treatment of African-Americans in this political climate — and then offers some answers.

“Everybody gotta fight for equal rights,” he argues, rhyming so breathlessly fast, it sounds as if he’d need to spend some quality time with an oxygen tank afterward.

“To make it happen though we gon’ need patience / And not violence, giving hospitals more patients,” he continues.

“Don’t burn down the mom and pop shop / I’m just as angry another person got shot / Don’t be angry at the color of they skin / Just be happy that as a people we could begin again.”

He also addresses his biracial heritage.

“I know some people wish I’d act white instead,” he raps. “Say I’d use my pigment as a manifestation to get ahead.”

Speaking of which …

He’s one of the more articulate voices for diversity

His skin tone is the opposite of what life can be like for a biracial child: fair.

“I’m just as white as that Mona Lisa / I’m just as black as my cousin Keisha,” Hall rhymes on “Black Spiderman,” and yet, as the son of an African-American father and a white mother, Hall struggled to find acceptance from either community as a kid.

“White people told me as a child, as a little boy, playin’ with his toys / I should be ashamed to be black,” Hall recalls on “Everybody.” “And some black people look ashamed when I rap / Like my great granddaddy didn’t take a whip to the back.”

Growing up, Hall felt caught between these two worlds, his identity drawn and quartered along racial lines.

Of course, biracial rappers are hardly unprecedented — two of hip-hop’s biggest stars, Drake and J. Cole, also have white mothers — but few of them address the feelings of insecurity and alienation that such a background can foster as candidly as Hall does.

He has taken it upon himself to stir this melting pot.

“This is for every color, every creed,” Hall announces on “Everybody.” “Music does not discriminate / Music is made to assimilate.”

He’s a conscientious capitalist

Hall’s thing: empty G-strings, full pockets.

“You in the club throwin’ dollars, but I’m savin’ mine so my kids go to college,” Hall explains on “44 More.” “Or maybe whatever they wanna do / Just as long as they never say / Daddy blew 20 million dollars.”

Sure, Johnny Depp levels of conspicuous consumption have long been a hip-hop staple, and you can understand why: If you come from poverty, as plenty of rappers do, you may very well want to revel in the fruits of your success as publicly as possible.

For other MCs, adopting the trappings of wealth, even if they’ve yet to really earn said riches, is a way of dressing the part while striving toward their aspirations — yeah, there may be Lamborghinis in the video, but in plenty of cases, they’re promptly returned to the dealership afterward.

Now, Hall isn’t above flaunting his considerable bank account.

“I just paid $10 million in taxes,” he announces at the outset of “Wizard of Oz,” alluding to the signing of his most recent record contract, allegedly worth three times that.

But on that song’s chorus, he also puts his affluence into perspective.

“If they tell you money make you better than others, then somebody lied,” he asserts.

“Money don’t mean (expletive) without self-respect,” he elaborates on “State of Emergency.”

This from a man rich in both.

Contact Jason Bracelin at jbracelin@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0476. Follow @JasonBracelin on Twitter.