Once a teacher, this secretive Vegas landlord built an empire. Then 6 died.

A deadly apartment fire in downtown Las Vegas exposed a troubled real estate empire where property bills sat unpaid, workers claimed wage theft and inspectors issued hundreds of health and safety code violations.

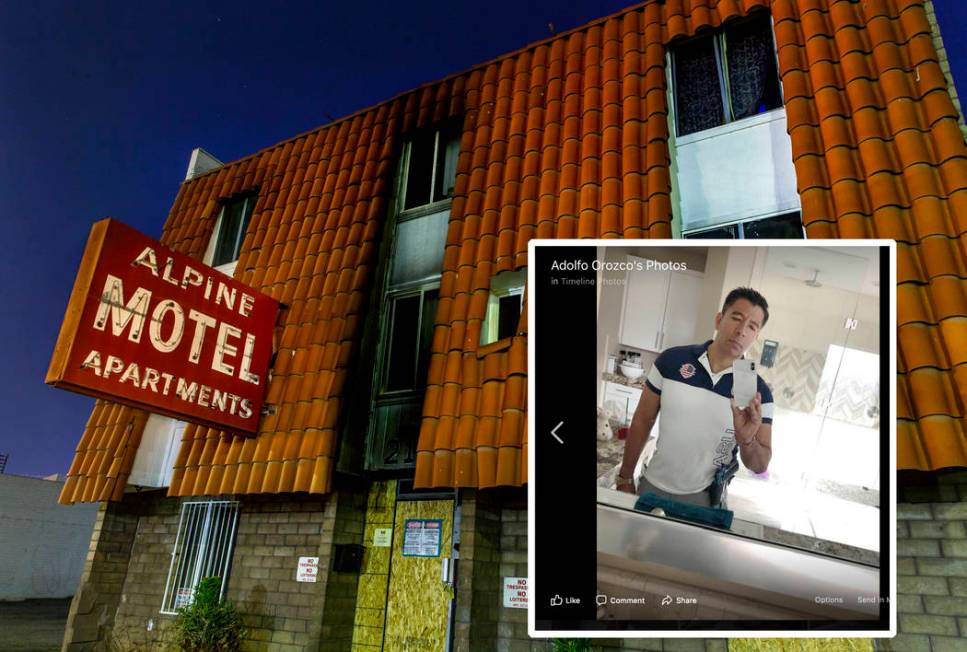

Adolfo Orozco, a former teacher described as “extremely private,” oversees the multimillion-dollar portfolio, which he amassed with his wife and four companies tied to them, a Las Vegas Review-Journal investigation has found.

It’s a picture of wealth that spans the Las Vegas Valley: apartment and hotel buildings stuffed with studios, pockets of rental homes and a 6,250-square-foot mansion where the couple appear to live, nestled within a gated, guarded community in the foothills of the southern valley, records show.

But the Alpine Motel Apartments fire brought scrutiny to the landlord at its helm, triggering a criminal investigation and exposing Orozco to wrongful death lawsuits. The December tragedy left six dead, and inspectors in its aftermath noted more than 40 fire code violations, including an exit door bolted shut from the outside.

Orozco armed himself with high-profile defense attorneys. But problems plagued his enterprise long before the blaze, according to interviews with former tenants-turned-workers and hundreds of documents examined by the Review-Journal.

The people Orozco hired were often homeless or poor, struggling to secure a job and a roof over their head, either because of personal hardships, addiction or prior criminal convictions. He offered them a place to stay and work.

But many told the Review-Journal they never received a paycheck or consistent cash flow from Orozco.

Records also show basic utility bills at the properties often went unpaid, along with property taxes and business license fees. Multiple properties faced foreclosure proceedings, and government inspectors found hundreds of fire, health and building code violations.

“He’s a straight slumlord,” said Audrey Palmer, who cleaned rooms and worked security for Orozco while living at the Alpine for seven years. “He doesn’t take care of his people.”

Orozco, who also goes by Adolfo Orozco-Garcia, has yet to grant an interview or release a statement since the fire. Dominic Gentile, his criminal defense attorney, reviewed the Review-Journal’s findings but declined repeated interview requests.

But those who knew Orozco, as well as public documents, helped piece together parts of his life.

The 43-year-old father has only lived in the Las Vegas Valley since about 2013, records indicate. But he has been amassing his horde of local properties since at least 2004, when — before the empire, before the fire and before he ever fell under the microscope — he was working in Northern California as a second grade teacher.

Immigrating from Mexico

Raised in the countryside of central Mexico, Orozco immigrated to California’s Napa Valley when he was 15, according to application materials he submitted for his teaching job years later.

After a construction gig fell through, his father found steady work in the region’s vineyards. Orozco joined him after high school classes and on the weekends, grafting grapevines to support his family, he later told a college adviser.

But Orozco’s sights were set on something greater.

“At that time, a lot of students who were in Adolfo’s situation didn’t have any aspirations of going to college or university,” said Hector Brambila, his academic counselor in high school. “He was one of those cases that was special and unique. He broke the mold.”

A good-natured and outgoing teenager, Orozco was also a model student, Brambila said. Whenever the two met, Orozco would share his dream of becoming a bilingual teacher. He wanted to help local children who, like himself, were growing up in Spanish-speaking homes.

In 1994, Orozco became the first member of his family to attend college, Brambila said. While enrolled at Sonoma State University, he began working with a tutoring program that served migrant children. He graduated with honors in 1998, receiving a bachelor’s degree in Chicano and Latino studies.

That year, Orozco began working as a bilingual second grade teacher at Shearer Elementary School in Napa. Salary records show he made about $43,000 in 1999, but by 2011 he made about $70,000 a year.

Among his co-workers, Orozco mostly kept to himself, according to Guillermo Torres, a longtime Shearer teacher who overlapped with Orozco’s nearly 15-year career. Little was known about Orozco by the time he resigned in 2013.

“He was an extremely private guy,” Torres said. “We always kind of joked he lived this alternate life we didn’t know about, like a double agent.”

Growing his real estate empire

Six years into teaching, records show, Orozco did begin building an alternate life, investing in real estate in neighboring Nevada.

Byron Jackson, who would later work for him, said Orozco tried his hand at the new endeavor after seeing how much a relative made flipping properties in California.

In 2004, Orozco bought his first local property, the Dragon Motel in downtown Las Vegas, for $1.55 million.

In 2007, a year after traveling to Las Vegas to marry Erika Ayala, Orozco bought his second local property, a four-bedroom suburban home in North Las Vegas, where records indicate he relocated after resigning from his teaching career.

Orozco’s investing flourished during the Great Recession, when the housing market was oversaturated with distressed and discounted properties. In 2009 alone, he bought 10 foreclosed homes for less than $400,000, local records show.

“You were buying at pennies on the dollar of today’s values,” Las Vegas Realtors president Tom Blanchard said. “Anybody that had the ability to scrape up some dollars was coming here to lay down their money.”

In 2013, Tony Hsieh’s Downtown Project — which had recently begun investing in downtown Las Vegas real estate — purchased the Dragon Motel for $1.15 million more than Orozco had originally paid for it.

About two weeks later, Orozco acquired the Alpine for $805,000 under Las Vegas Dragon Hotel LLC, one of four companies he and Ayala manage or have ownership stakes in, including Elite1 LLC, Galeana LLC and Cancun LLC. Las Vegas Dragon Hotel bought three more hotels: the Economy Motel in downtown Las Vegas and the Casa Blanca Hotel and Starlite Motel in North Las Vegas.

More recently, their holdings have stretched beyond Nevada’s boundaries to include a motel in Tucson, Arizona, and a hotel in northwest Louisiana.

All told, records show Orozco, Ayala and the four companies have spent more than $8 million on Las Vegas Valley real estate and currently own more than 170 housing units spread across 24 properties, including the couple’s mansion, valued at about $1.5 million. They’ve spent more than $3 million on properties outside Nevada.

But records indicate the couple and companies struggled to meet basic financial obligations tied to those investments.

Orozco’s home in North Las Vegas was threatened with foreclosure proceedings four times between 2011 and 2015 after he missed mortgage payments.

From November 2013 through December 2016, Clark County cited several of the properties for nearly $22,000 in unpaid taxes, interest and penalties. In 2017, three hotel business licenses expired because of unpaid renewal fees.

As of February, the properties had received about 350 liens for failing to pay sewer, trash or homeowners association fees on time, which led to five facing foreclosure proceedings at least once.

Records indicate the couple and companies eventually caught up on almost all missed bills and ultimately never lost a home to foreclosure. But as of Friday afternoon Orozco, Las Vegas Dragon Hotel LLC and Cancun LLC owed Las Vegas more than $15,000 in overdue sewer fees combined, the city’s website showed.

Las Vegas business attorney Aviva Gordon said she was stunned by the findings.

“This is an extraordinary amount of accrued and unpaid expenses for things that are for the most part knowable and predictable,” she said.

Orozco’s flashy persona

Despite the financial struggles, Orozco has maintained a flashy persona.

Former residents said when he visited rental properties, he often pulled up in a Corvette or another lavish car. On Facebook, he posted photos of himself drinking wine in his mansion’s hot tub and mirror selfies flaunting an expensive handgun on his hip. He sometimes had that weapon on him, as well as a rifle, during site visits, workers said.

Outside of real estate, Orozco works as a “weight loss specialist” with Herbalife, according to his LinkedIn page. The multi-level marketing company sells “nutrition products,” including teas and shakes, according to its website.

A photo on his LinkedIn page shows Orozco and Ayala in Herbalife shirts with general admission badges for a company conference around their necks. In a Facebook comment from February 2019, Orozco told someone he was still working with Herbalife, noting, “I reached president status!!”

But records show his apparent personal wealth and professional success were not reflected in the upkeep of the properties tied to the couple.

Government inspectors have documented almost 300 separate health, fire and building code violations at various rental properties within their portfolio since 2013.

Ahead of the December blaze, records show the Alpine alone outright failed 11 of its 14 fire inspections under Orozco’s tenure.

In May 2019, the Southern Nevada Health District held a “sanitation intervention” after the Starlite Motel repeatedly failed health inspections, a spokesman said. The agency mandated that the Starlite, Economy and Casa Blanca have working smoke alarms, adequate pest control measures and sanitary mattresses in each guest room.

The mandate was not extended to the Alpine because the property operated as an apartment complex, according to the health district, which does not regulate private residences. The agency considered the other three properties short-stay hotels.

But residents who survived the Alpine fire told the Review-Journal that the building’s heat often went out in the winter and repair requests went unaddressed.

Ray Nichols, a plumber who lives next to the Alpine, said he saw the building’s delapidated condition firsthand when he performed repairs there in the spring of 2019 as a contract worker. Inside, he spotted leaks and water damage on walls and ceilings. Regardless, Nichols said he was instructed to make repairs “as quick and simple as possible” by the building’s property manager.

“It was just so neglected and ignored that when it came time to work on it, it was overwhelming,” he said. “There were just too many repairs.”

Workers claim wage theft

As property bills went unpaid, some of Orozco’s workers claimed they never saw paychecks, records and interviews indicate.

LaKeisha Davis began working for Orozco as a housekeeper in late 2018, not long after taking a room at the Casa Blanca. She is one of seven former workers to file unpaid wage claims against Orozco since 2016. When given the opportunity, Orozco contested or settled all of them.

Davis said she signed no employment paperwork. Instead, she said she was told she would receive $5 cash for each room she cleaned, and if she kept up with rent, she would be allowed to live at the property over the long term. At the time, rent at the Casa Blanca ranged from about $500 to $600 a month to a daily rate of $45 on weekdays and $55 on weekends, Davis said.

The 32-year-old said it was a welcome offer. She had been out of work since a car crash in 2013 bankrupted her in medical debt and left her with random seizures, court records show.

But Davis told the Review-Journal she never saw direct payment. Instead, as she understood, the money she earned on any given day was automatically funnelled into her daily rent.

That added up to more than $1,300 in daily rent deductions each month without any of the money coming directly to her, she said, preventing her from saving up and paying a much more affordable monthly rent or spending her earnings however she saw fit.

“Basically, you’re living in a hotel, but you’ve gotta figure out how you’re going to eat, how you can go to the doctor,” said Davis, who claimed that Orozco owed her $10,040 in back pay.

Since 2018, Nevada law has limited the amount of wages an employer can deduct for lodging to $41.25 per week, according to Labor Commissioner Shannon Chambers. That’s about five hours of work under the state’s minimum wage.

Some residents who did work for the properties told the Review-Journal they only had success squeezing money out of Orozco when they asked him for a couple bucks during site visits.

Others, including Davis, said they sometimes signed out “petty cash” from property managers — a personal portion of about $150 that each building was supposed to have on hand for cleaning supplies or locksmith calls.

“You’re not supposed to,” Davis said. “But how am I going to eat?”

The labor complaints filed against Orozco claim workers were owed anywhere from about $3,500 to more than $69,000 in back pay. The workers claimed that they had entered oral agreements with Orozco and were supposed to be paid in cash.

Most claims were never resolved, sent back because of paperwork errors. Davis’ complaint was dismissed because she listed an invalid current address.

In at least one claim that he contested Orozco referred to former houeskeeper Jamie Lynn Batalias as an independent contractor. He noted that the Economy, where she was staying and working, did not accept “partial payments” for monthly rent.

“Jamie Batalias rarely had large amounts of money so she would choose chose (sic) to pay daily,” he wrote to the commissioner’s office.

Five former workers, including Davis, also told the Review-Journal that — while working for Orozco in Las Vegas — they were never asked to complete tax forms, raising questions of whether Orozco and the employees were paying into federal programs like Medicare and Social Security.

If not, those who were employees could have missed earning Social Security benefits, according to Las Vegas labor attorney Leon Greenberg.

“This is an area where government enforcement is really, really important,” Greenberg said.

Davis, who said she intends to correct her wage claim and submit a new one, called Orozco “the worst man that you could ever meet.”

“It’s not even his personality,” she said. “It’s the way he handles things.”

But other workers said Orozco was just trying to help them out.

In one wage claim case from June 2017, a property manager named Devine Ducksworth claimed he was owed $10,000 for 11 months of work at the Economy Motel. But the case was dismissed after Orozco produced a settlement he had signed two months earlier with Ducksworth, agreeing to pay him $200 for all work done in 2016 and 2017 and “not to press criminal charges” for unspecified reasons, records show.

Ducksworth told the Review-Journal that Orozco started paying him better after the dispute, and several times, when he was in a bind, his old boss lent him money.

“He took a chance on me and helped me turn my life around,” Ducksworth said. “He took care of all his employees.”

In January, Batalias dropped her $18,000 wage claim against Orozco just five days after he contested it.

Batalias told the Review-Journal in a letter that she dropped the claim after sitting down with Orozco, who told her, “You know there was no need for any of this” and helped her out with “a little bit of money to get me going again.”

In a phone conversation, Batalias said Orozco was unconventional but called those who didn’t agree with him “haters.”

“He might not be the best landlord or employer, but he’s a good person overall,” she said. “Everybody has their flaws.”

Safety hazards

At least twice on the job, Orozco’s workers faced potentially hazardous situations, records obtained by the Review-Journal also show.

In 2016, a Casa Blanca housekeeper claimed that workers were expected to “pick up used needles with their bare hands,” according to an anonymous complaint submitted to the Nevada Occupational Safety and Health Administration. The housekeeper also reported that workers were not provided bleach to disinfect linens stained with blood.

Records show an inspector with the agency did not find evidence of the housekeeper’s claims, noting that Orozco willingly granted access to the property and answered all of the inspector’s questions.

But as a result, Orozco did face $5,400 in separate fines for failing to adequately train his housekeeping staff for exposure to chemicals and bloodborne pathogens.

He paid half that amount, arguing the initial penalty would have been burdensome to his business. Records show the violations were corrected and the case was closed.

The same year, Nevada OSHA opened a separate case against Orozco after a repairman without adequate asbestos-exposure training had been permitted to do work inside the Alpine, which was presumed to contain asbestos.

The Alpine was built in 1972, and asbestos by law is presumed to be in all buildings constructed before 1981, according to the agency.

“The employer told (the inspector) he knows asbestos exposure is bad for your health, but he didn’t know he needed to do an asbestos survey to determine the presence of asbestos in the building,” records show.

A subsequent survey confirmed its presence in the building. Orozco was ultimately fined $2,400, which he paid in April 2017 to close the case, records show.

The asbestos documentation is relevant to ongoing Alpine fire litigation, as residents who were forced to abandon their belongings during the blaze have not been allowed to collect them since — chiefly because of the ongoing criminal investigation, but also because of asbestos exposure concerns.

Teri Williams, a Nevada OSHA spokeswoman, confirmed in February that the agency had opened a third case against Orozco following the fire. That’s because one of the six people who died was Don Bennett, a maintenance man who lived and worked at the property.

Williams said the agency is working with local law enforcement and other government agencies “to conduct a thorough investigation.”

As of Friday, no new Nevada OSHA violations had been issued, and no criminal charges had been filed.

In an emailed statement, Clark County District Attorney Steve Wolfson said in February that his office regularly meets and communicates with Las Vegas police about the Alpine criminal investigation.

“The investigation is ongoing and is moving towards completion,” he said in the statement.

Since the fire, eight properties linked to Orozco and Ayala have been listed for sale online: three hotels and a bundle of triplexes and fourplexes.

The hotels were listed as a $5.5 million package deal, but individual sales are also being considered, according to the advertisement. The bundle of divided buildings was listed as a $1.5 million package.

David Howes, the real estate broker handling the sales, declined to answer questions about the listings, instead directing questions to Gentile, Orozco’s defense attorney.

The attorney declined multiple interview requests for this story and ignored questions from a Review-Journal reporter at the Regional Justice Center last week.

The Review-Journal’s investigative team focuses on reporting that holds leaders and agencies accountable and exposes wrongdoing. Contact Rachel Crosby at rcrosby@reviewjournal.com and Michael Scott Davidson at sdavidson@reviewjournal.com.