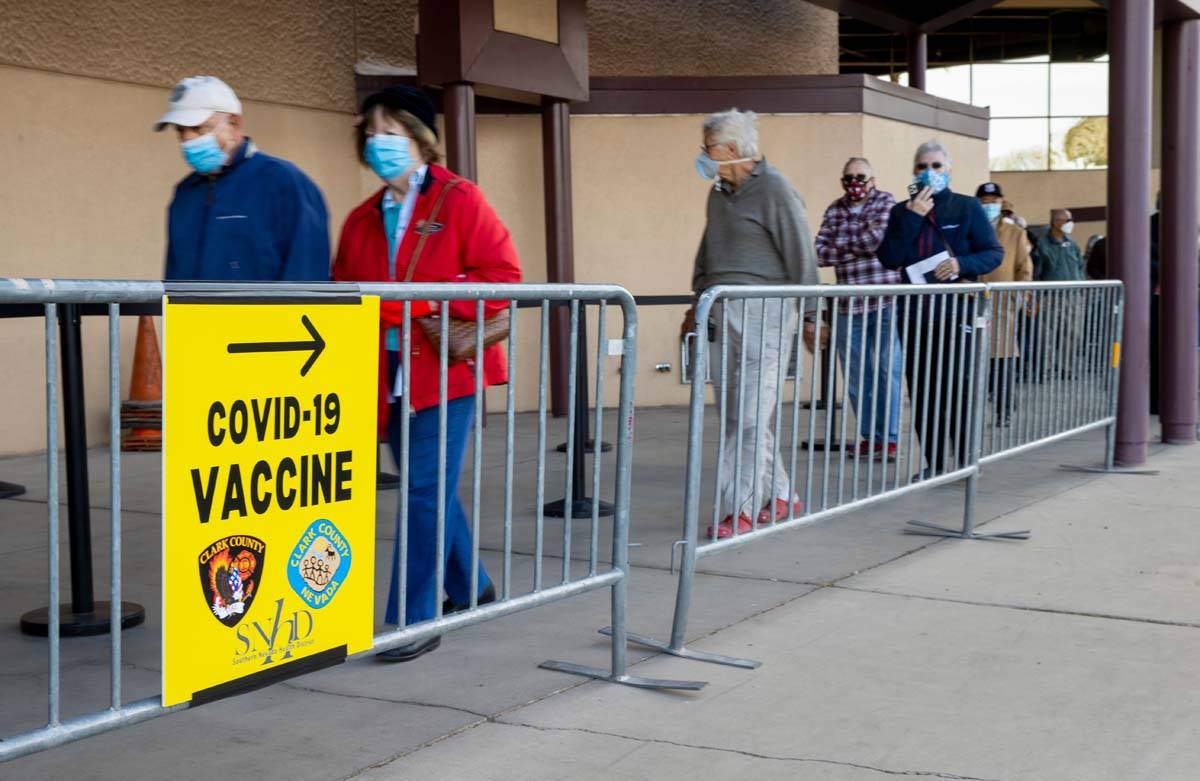

Appointment, ID not always required at vaccination site

The 71-year-old raised his arms above his head in triumph after getting a shot of the COVID-19 vaccine Tuesday morning at the Cashman Center downtown.

“Yay!” shouted the man, who gave only his first name, Mike.

On Monday beginning at 3:30 a.m., he’d checked the Southern Nevada Health District’s online appointment portal every hour or so for any available appointment, with no success.

“And so I just came down here, and they didn’t even check for appointments,” he said.

Others told similar stories of getting vaccinated Tuesday without an appointment after receiving a tip from a friend or relative. Many said they had not been asked to show any form of identification to verify their age or employment. And some did not fit the current requirements for who is eligible to receive the vaccine.

Under state and county guidelines, the top priority groups for receiving the vaccine have been front-line health care workers and long-term care facility staffers and residents, followed by people 70 and older. On Friday, without announcing the change, the health district updated its appointment portal to allow the next priority group, termed “front-line community support,” to also make appointments.

This broad swath of the workforce includes, among others, elected officials and their staffs, child care workers and the remainder of the public health workforce. Other vaccination arrangements are being made for teachers, who also fall into this group.

Meanwhile, older residents eligible for the vaccine have been complaining in force that although eligible for the vaccine, they have been unable to obtain appointments, not only at Cashman but at any vaccination site.

Not solving the problem

Medical ethicist Arthur Caplan said it is a mistake not to be getting the vaccine first to those identified as needing it the most.

“The point of current vaccine policy, from the Trump administration to the Biden administration, is to get vaccines to those most at risk of becoming ill or dying,” said Caplan, professor of bioethics at New York University’s Grossman School of Medicine, who wrote a 2017 book on vaccine ethics and policy. “Every government, county, state has an obligation … to try and do that because it’s ethically sound.”

But there isn’t enough vaccine allocated yet to vaccinate all of those over 70, and there also are logistical issues in reaching an older population, said Caplan, who is critical of the use of online appointment portals for a group that is generally less tech-savvy. But instead of solving the problem, officials are giving the vaccine to additional groups.

He leveled his harshest criticism over failures to require identification at a vaccination site.

“How are we doing rationing of life-saving vaccines without asking for ID? That is unconscionable,” he said. In doing this, “you really have given up following the high-risk guidance. When you don’t ask for ID, you’re again just saying … ‘I can’t figure it out, so I don’t want to know.’”

A representative of Clark County government, which manages the site, said that the majority of people served at Cashman have had an appointment and that those who arrive without one may be turned away.

“We are continuing to adjust our processes at the Cashman Center site to make it as efficient as possible based on available day-to-day supplies of vaccine,” spokeswoman Stacey Welling said in an email. “Appointments are required, and those arriving on site should be prepared to show ID and to verify employment.”

On Monday, when asked about the policy for walk-ins at Cashman, health district spokeswoman Jennifer Sizemore said appointments are required for receiving the vaccine. On Tuesday, she said the district does not manage the site and deferred comment to Clark County. Appointments and ID are required at health district sites, she said.

Practices differ from policy?

There was example after example Tuesday of practices differing from stated policy at Cashman.

One 65-year-old retired man who was vaccinated without an appointment said he wasn’t previously aware that he did not meet the current age criteria of 70 and older.

“The criteria is changing all over the country,” said the Henderson man, who gave only his first name, Bob.

Bob, who said he has underlying health conditions that put him at higher risk for COVID-19, said a site supervisor made an exception in his case.

A couple who identified themselves as Tim and Connie got the vaccine without an appointment, and Tim is only 69. Adding to the confusion was a sign at the site that said people 65 and older are eligible, they and others interviewed said.

A middle-aged man and a woman, both of whom work at an assisted care facility, said they got the vaccine without an appointment and without showing identification. Under the priority system, staff members at long-term care facilities are currently eligible for the vaccine.

A 25-year-old man, the youngest person spotted leaving the vaccination site, said he is a public health volunteer, a group eligible for the vaccine. However, he said he wasn’t required to provide an ID confirming his status.

Of the 15 people interviewed Tuesday, the only ones who provided their full names to a reporter were those over age 70 who had appointments.

Orderly, efficient process

Those interviewed said the process at the site was orderly and efficient, and some defended the lack of strict enforcement of the appointment and identification requirements. They said that they’d gotten through the line in an hour and that requiring identification would have slowed the process.

“They’re getting it done,” Mike said. “Don’t criticize them for it.”

But while the ultimate goal may be to get the vaccine into as many arms as possible, there are other considerations, a UNLV medical ethicist said.

“I would say in the long term, we want to encourage vaccine uptake, and we want to get as many people vaccinated as possible,” said Johan Bester, an assistant professor and director of bioethics at the UNLV School of Medicine.

“In the initial stages, it is important that we prioritize those people who need to be prioritized, those who are vulnerable, those who are at the front line. And so we must strike that balance.

“If it is indeed so that those who need to be prioritized are crowded out, then we need to think again,” he continued. “But I’m OK with a sort of a slow but deliberate easing of restrictions and barriers in front of vaccination, as long as it’s communicated well and deliberately.”

Caplan said fault doesn’t lie with those who got vaccinated outside the stated rules, since they were only making use of the system that was in place. Instead, he faulted those in charge.

“If you want to say, ‘We can’t handle distribution by age or health care worker status’ … then admit it. Don’t just sneak around and say, ‘If you’re smart enough and lucky enough to figure this out, come on down. And we’re also going to make it easy for us because we’re not going to worry about who you are.’ I mean, that’s just giving up.”

Bester said that lack of transparency creates a credibility problem.

“I think transparency and honesty are important public health values,” he said. “And we do damage to credibility if we do one thing and say another. So I must be clear that … I am not aware that this is the case.

“But if it is the case that people can get in without appointments, and the official line is that it is appointments, it does undercut the credibility of your public health messaging,” he said.

Contact Mary Hynes at mhynes@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0336. Follow @MaryHynes1 on Twitter.