Study challenges need for lymph node removal in cancer patients

When the news broke about a study that found many women with early breast cancer need not have all their underarm lymph nodes removed — even if they contain cancer cells — Christine Wunderlin was both happy and disappointed.

She is happy that more women will be able to escape the lymphedema, a chronic, often painful swelling in the arm caused by the retention of lymph fluid, that she has experienced as a result of the excision of 11 nodes.

But she can’t help being disappointed about ever having to go through the major lymph node removal in the first place.

“Exactly a year after I have my procedure done, they come out with this,” she said Tuesday. “My breast surgery has been easier to deal with than the lymphedema.”

Wunderlin, who runs a career counseling business, must regularly visit Dr. Richard Hodnett’s Lymphatic Center of Las Vegas, where a specialized therapist massages her arm to disperse the lymph fluid through pathways in her body that are still functioning.

And she must wear a compression garment on her left arm for the rest of her life or the lymphedema may well become disabling.

“If I don’t keep it in check, even being able to wear a blouse can be problematic,” she said.

According to the study published in the Feb. 9 Journal of the American Medical Association, researchers found that removing lymph nodes in women with early stage breast cancer — the disease strikes about one in eight women — did not improve their chances of a recurrence or surviving when compared with leaving the nodes behind during breast cancer surgery.

Women in both groups had about a 92 percent chance of survival.

on the cutting edge

Dr. Josette Spotts, a 54-year-old breast surgeon affiliated with Comprehensive Cancer Centers of Nevada, was not at all surprised by the findings of the study that promises to change what has been standard medical practice for decades.

“I’ve stayed on top of the research and for the last several years have given my patients who fit the proper profile the option of not having their lymph nodes removed,” she said. “I just hate to see women go through lymphedema unnecessarily. It can be debilitating and the literature shows there’s about a 17 to 20 percent risk (of suffering from lymphedema) when you remove many of a woman’s lymph nodes.”

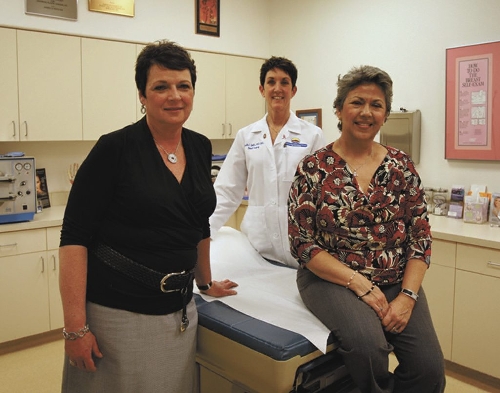

Two of her breast cancer patients who opted not to have lymph node removal as far back as four years ago, Patricia Hovey and Christine Santiago, sat in the physician’s Henderson office last week and discussed why they chose to forgo excision when the standard of care at that time was to have the lymph nodes removed. Both are now cancer free.

“In a way I realize it was a leap of faith,” said the 56-year-old Santiago, who was trained as a registered nurse and works in risk management administration for the Clark County Administration Department. “But I was impressed with Dr. Spotts’ knowledge of the research and I also know that medicine is sometimes slow to change the legal standard of care. I’m obviously happy that the study validated my faith.”

The 61-year-old Hovey, who has been laid off from her job as a sales manager for Mexicana Airlines, said Spotts carefully explained all the possible pros and cons. “When she said I was a candidate for not having the removal of the lymph nodes, it came down to the fact that I trusted her.”

Nearly 1,000 women, with a median age in the mid-50s, were involved in the study carried out at more than 100 medical centers throughout the United States. The women were followed for a median of 6.3 years.

About 20 percent of breast cancer patients meet the criteria of the study, where tumors are less than 2 inches across and cancer has not spread outside the nodes.

Spotts, a graduate of the Wayne State University School of Medicine in Detroit, had told the women that the research she studied — later borne out by the study — found that removing the cancerous lymph nodes proved unnecessary because the standard therapy today in addition to a lumpectomy, radiation and chemotherapy likely killed the disease in the nodes.

Lymph nodes, small bean-shaped glands, help eliminate bacteria and viruses and are needed to drain and regulate the flow of lymphatic fluid. Spotts said that until research and technology proved otherwise, it made sense to remove lymph nodes as part of breast cancer surgery because the breast tissue lies close to the lymph nodes and lymph can harbor wayward cells that travel out of the original tumor into other parts of the body.

“We keep making advances, and as a physician you want to make sure your patients get the best care in as timely a fashion as possible,” Spotts said. “For a long time we only did mastectomies (removal of the entire breast) and then we found out that lumpectomies (removing only part of the breast) followed by radiation have basically the same survival outcomes.”

mapping the nodes

Both Hovey and Santiago were found to have cancer in their lymph nodes when Spotts did a procedure known as sentinel node mapping as part of their breast cancer surgery.

The sentinel node is the first lymph node or nodes to receive drainage from a cancer-containing area of the breast.

Generally, about an hour before a woman enters the operating theater for breast cancer surgery, she is injected with a radioactive tracer that is used for the mapping. Soon after the patient is on the table, the surgeon uses a handheld Geiger counter that sounds off as it finds the radioactive tracer in the lymph nodes. A blue dye helps the physician get visual confirmation of the sentinel node on a monitor.

With an incision in the armpit, the surgeon takes out the node, sending it to a pathologist to be checked for cancer. The lumpectomy follows.

“In the past, if the sentinel node was cancerous, we’d do another surgery later for the other nodes,” Spotts. “Now, fortunately, we often don’t have to go through that. The chemo and radiation will kill the disease in the nodes.”

Spotts has known that she was taking a risk by telling some of her patients that she believed they could opt out of lymph node removal surgery.

“If it recurred because of that when the standard of care was removal, I could have financial liability,” she said. “But I feel an obligation to my patients to give them an opportunity for the best care that research shows is available.

Dr. Theodore Potruch, another Las Vegas breast surgeon who has given his patients the benefit of such an option, agrees with Spotts.

“It is imperative that we stay on top of the research for our patients,” Potruch said, noting that he hopes to start a trial therapy soon where cancerous breast lumps are rendered impotent through freezing rather than excision.

“It’s important that what we do leaves women scarred as little as possible both physically and emotionally.”

Though research may indicate that a new treatment option is possible, Spotts said she is never surprised when some women refuse it. Nor is she surprised that some doctors are reluctant to change what seems to have worked.

It is much easier for both patients and doctors to accept more cancer treatment on the basis of a study rather than less. Given that breast cancer kills 40,000 American women a year, it can be frightening to try what may seem, at first blush, less aggressive care, Spotts said.

“It’s hard for some people to get their arms around the fact that less can actually be more,” she said.

Some women not only favor lymph node removal regardless of research, but also mastectomies rather than lumpectomies “because they think it’s better to be safe than sorry.”

“The fear is very real and very understandable. I want to do what makes the patient most comfortable.”

To Christine Santiago, it is critical that women weigh carefully what their doctors say in conjunction with their own research.

“You have to find out as much as you can about what you’re going to do with this disease because it can mean your life. And then you have to hope you make the right decision.”

Contact reporter Paul Harasim at

pharasim@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-2908.