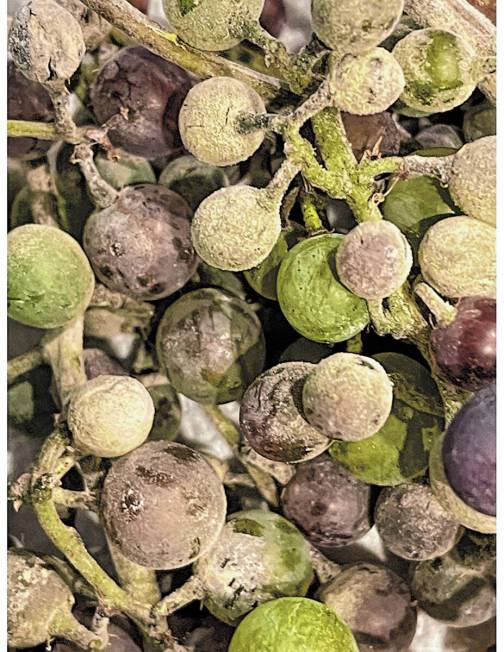

Wet spring conditions can lead to bunch disease on grapes

Q: I am a big fan of your column, but I haven’t seen any answers about what’s happening to my grapes. Please advise. I have four grape plants and maybe 10 percent to 15 percent have this white stuff on certain bunches.

A: It’s a disease of the bunches; a “bunch disease.” I thought this might happen mostly because of our wet spring.

Bayer Garden Products tells us, when treating for grape bunch diseases, that about half of the improvement is due to better air circulation and the other half using a copper-based fungicide. They are right collectively, both downy and powdery mildew are called bunch diseases.

This looks like one of the grape diseases, probably grape downy mildew. Try removing bunches and leaves so that you have one bunch every foot.

If it is tight with leaves, remove some of the leaves as well to improve air circulation. Don’t remove too many leaves so that you get direct sunlight on the grapes or limbs. You want to improve the air circulation around the bunches and the berries but without putting the bunches (and limbs) in direct strong sunlight for any length of time.

You can apply a spray mixture of a copper-based fungicide according to the label. Liqui-Cop and Bordeaux sprays come to mind, but any copper-based fungicide (a fungicide that includes copper in the ingredients) should work.

You may have to repeat the application. Read the label. Grapes must be on the label of a fungicide because of testing and recommendations concerning the rate of application.

Remember fungicides help prevent plant diseases but do not cure the plant of a particular disease. You are spraying early to prevent the spread of a bunch disease. There is some evidence that Neem oil has given some protection, but copper-based fungicides are better.

You may be too late with a spray of any kind, but it is worth a try. Do it very soon and follow label directions for controlling these bunch diseases on grapes. Next time apply your favorite spray earlier in the season to prevent bunch diseases.

Q: Over a year ago our city planned a new extension to a community park and put in a dirt trail surrounded by native plants. They dug wells and put in an assortment of plants and trees with no water source. The first month they used a fire hose from the hydrant to water the plants. Since then, nothing. I counted over 185 dead plants this morning. Are there certain plants for that zone or location that will be able to survive without any water?

A: Not really, no. Even cactuses occasionally need water to get established and grow after planting. Cold-hardy desert plants are best planted in the fall; winter tender plants in the spring. In very dry summers, desert plants will need supplemental water once a month or more to look good and survive.

Cities and homeowners are not Mother Nature. Even so-called desert plants need water (and usually some soil improvement) periodically to look their best. Homeowners won’t tolerate plants that look bad.

For each plant that survives in the desert after a rain, thousands of plants don’t. The advantage of desert plants is their ability to survive periods of time without water.

To think we can guess where plants will survive after planting is pure arrogance. Desert plants respond to water. They respond best when the water is applied to the same spot. They respond by growing.

Some, like Texas ranger (the barometer plant of the Chihuahuan Desert) produce flowers on new growth after a rain. As these desert plants get drier, they first drop their leaves (if they have any). Even cactuses will put on some new growth after a rain and may even flower.

Q: Now that it has gotten hot, my fruit trees (some new, some established) don’t look so good.

A: When fruit trees are first planted, they may look good. That is because they are watered correctly for the first three or four years.

After that fruit trees get bigger, and need more water applied wider and to the same depth. Don’t change how often they are watered. When they are watered, they need to be watered to the same depth, to a wider area and with an increasing amount of water each time they are watered.

What I find to be effective is to apply water to the area under a mature fruit tree (seven years in the ground and longer) that is about 6 to 7 feet wide. Much of the area watered depends on the soil you have, but most soils are a sandy loam when irrigated (even though they are hard when dry).

I prune fruit trees in the winter at 7 feet and let them grow during the year to close to 8 or 9 feet tall, not their full size. This pruning allows for ladderless fruit harvesting.

To do this I water the fruit trees 18 to 24 inches deep in the soil. The area I want to apply water is about half the area under the fruit trees. This usually requires about eight drip emitters (or two concentric rings of drip tubing with emitters placed 18 inches apart) when the fruit trees have been in the ground five to six years. The rings are spaced 18 inches apart, too.

The fruit trees are planted about 10 feet apart in all directions. I prune them so they fit into this area, and you can walk around them to harvest, fertilize and prune.

Figs are good to have in the orchard because, in my experience, they grow but will not fruit if they come up short on water. Fruit is the first to go, not growth.

If you have fruit on your fig trees in July and August, then the other trees are getting the right amount of water, too. Figs are a water-indicator fruit tree for me.

Q: I have some newly planted peach and nectarine trees with sap coming from them. They don’t look healthy.

A: Borers are most likely the problem. On small, newly planted fruit trees, it doesn’t take many borers to kill the trees.

They usually attack the south or west sides of a trunk or the limb of a tree. That’s where there is sun damage. Painting these trunks and limbs with white latex paint lowers the surface temperature about 4 or 5 degrees. It may be enough in some cases. But shade is better.

The sun plays a role also. Direct sunlight on the trunk of a thin-barked fruit tree can be a problem. The smell of sunburned and dying or dead limbs and trunks attracts female borers that are looking to lay their eggs, scientists believe. When limbs and trunks of newly planted fruit trees have sun damage, then borers are more likely to be found.

What to do? Shade the young tree from western and southerly direct sunlight. Paint the trunk with diluted white latex paint. As a last ditch effort, drench the soil around the tree after it flowers (if possible) with a borer systemic insecticide and don’t eat the fruit for at least 12 months after the application.

Q: I need some help. I planted a pomegranate tree about three years ago. The tree looks great and there are always lots of fruit. The problem is that by the time the fruit gets up to about 2 inches in size they are splitting open. Can’t figure out the reason and I am yet to harvest a good pomegranate. It gets full sunshine in summer and water three to four times a week. Any suggestions?

A: Are the arils (pulp) sweet? Maybe it is ready to harvest.

First of all, the fruit should be larger than that. The fruit should get larger as it gets older and it is pruned correctly. A high percentage of small fruit is produced on smaller branches.

Get rid of the suckers at the bottom of the tree and force production on to about five or six main limbs that you keep. The best fruit is produced on older wood. Small fruit is produced on young and smaller wood.

Fruit splitting is oftentimes a harvesting problem. Taste the seeds inside (called the arils) and see if they are sweet. There is a wide variation in flavor so don’t be surprised if the fruit taste is puckery.

If the arils are sweet, it might be ready to harvest. Pomegranates are ready to harvest, depending on the variety, from September (Utah Sweet) until early December (Wonderful). The fruit should not crack unless they are past their harvest time.

If the fruit is splitting before it is ready to harvest (not sweet yet but getting there), then it is a watering issue. Just like melons, as the rind sets up for harvest (sugars are accumulating) watering becomes critical. Watering when the rind gets hard (and it doesn’t need it) will split the fruit.

Bob Morris is a horticulture expert and professor emeritus of the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. Visit his blog at xtremehorticulture.blogspot.com. Send questions to Extremehort@aol.com.