Houses of worship rely on faith, as well as security measures, for safety

At houses of worship across the valley, congregants gather daily for prayers, to attend services, to participate in activities and to work in ministries.

They pass through no gates. They require no paperwork. They need no appointment to attend a worship service. And they don’t expect their visit to be anything other than a meaningful spiritual experience.

Churches, mosques and synagogues traditionally have operated according to a model that involves few hurdles, encourages visits anytime and practices great measures of trust.

Usually, it works. But sometimes it doesn’t.

Houses of worship are vandalized. Money from donation boxes, or even religious articles, are stolen. And, in the worst cases, an open invitation to worship ends in worshippers being assaulted or killed.

On June 17, the murders of nine Bible study participants at a historic black church in Charleston, S.C., occurred after the suspect simply entered the church, sat down and joined in. The incident underscored a subtle but definite dichotomy of worship: How can the all-are-welcome philosophy be properly balanced with measures aimed at keeping worshippers safe?

Several valley clergy members say the Charleston shootings prompted questions from congregations about how safe they really are at worship.

Although their philosophies differ about how far a house of worship can go before the welcoming environment of a religious service becomes lost, they agree that after all that can be done has been done. It’s up to, literally, a higher power to take care of the rest, they say.

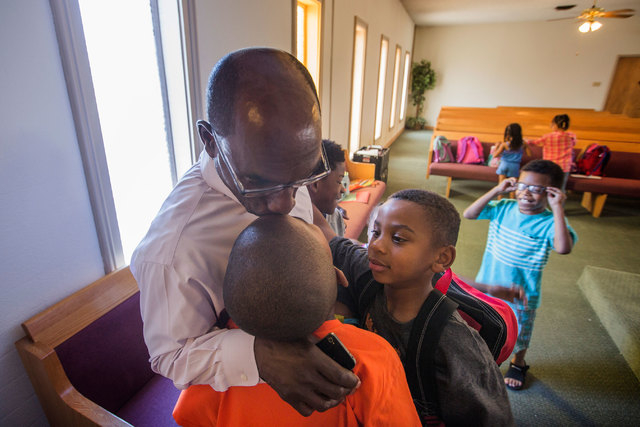

At First African Methodist Episcopal Church in North Las Vegas, the campus is busy not just for weekend worship, but also throughout the week — pretty much from morning until evening. The schedule is necessary to accommodate the church’s extensive roster of social service and community-oriented ministries.

Like most churches, the campus is welcoming by design.

“We have no bars on our windows. We have no graffiti on our building,” the Rev. Ralph Williamson, the church’s senior pastor, says. “We’ve never had any break-ins, and part of that is because we give back to the community.”

Among the church’s ministries are a food pantry and a “Take it to the Street” ministry that distributes food, clothing and hygiene items to residents.

“And we run tutoring programs and summer academies,” Williamson says. “So people know that (FAME) is a community church, and people protect those things that are representative of their community.”

Still, after the Charleston shootings, Williamson says some church members approached him about whether the church should be doing anything different.

“Are they concerned? Yes. Are they asking questions? Yes,” Williamson says. “But the biggest question that everybody is asking is, how in the world could this have happened in a sacred space? That is the biggest question. Everybody just seems to be so flabbergasted over trying to make sense out of it.”

“We do have all of the modern technology,” Williamson says, including cameras around the property, alarm systems and buzzers to admit guests into offices. Staff members also patrol the property to make sure buildings are secure, while, during services, congregants likely include police and security officers who also happen to be church members.

How far can — how far should — a pastor go to make a church secure? No pastor wants to dissuade guests from feeling welcome at church, Williamson says, but “the more you grow as a church, the more you become cognizant of individuals that are predators, and not everybody that comes to church means good things (to) the church. So your eyes are always open.”

Literally.

“We don’t lock the door when the (services are) going. We keep our doors open,” Williamson says. “But, believe me, people know. They always say, ‘Pastor, we can tell that your eyes are looking around,’ because I am looking and I’m always scanning.”

Ultimately, Williamson says, a pastor and a congregation can do only what they can do and then leave the rest to God.

“We try to allow the Spirit of the Lord to have its way regardless,” he says. “So the Spirit has to move freely, and people have to feel they can worship in an environment that’s healthy and conducive to the worship.”

For nearly 30 years, Catholics in Las Vegas have been able to spend an hour, or just a few minutes, with the Blessed Sacrament in the Chapel of Perpetual Adoration of the Eucharist at St. Bridget Catholic Church, 220 N. 14th St.

And for nearly 30 years, the 24/7 chapel has been the site mostly of surprising, uneventful solitude.

“There have been some serious issues when police have been called,” says the Rev. Dave Casaleggio, St. Bridget’s parish administrator, although arrests seldom have followed.

“But, short of that, there hasn’t been any robberies or anything like that,” says Casaleggio, who suspects that even those harboring ill intent “realize it’s a place of peace.”

Casaleggio is not one to put up hurdles that might make it harder for anyone to visit church. At St. Christopher Catholic Church in North Las Vegas, where he also serves as pastor, “our church is open all the time that the office is open, and the office is across the street from the parking lot of the church.”

There are cameras “so if something happened we’d be able to know,” he adds. “But it’s a matter of trust. And why choose to do that?

“Is there a chance things could go wrong? Yeah, but we have a pretty good record, and I think most people respect the church.”

Casaleggio, who also spent about 15 years in prison ministry, isn’t naive.

“I know that what happened in Charleston can happen here,” he says. “But I’m not going to let that control how I operate this place for the people of God.

“You’ve got to keep your eyes open and, hopefully, be able to respond if needed. But you can’t let an incident like what happened in Charleston control how you live and how you operate.”

The Rev. J. Barry Vaughn, rector of Christ Church Episcopal, 2000 S. Maryland Parkway, says, “The first thing to say (about the Charleston shooting is that) incidents like it are very, very rare. Church is still one of the safest places you can be.”

“Of course, we have to worry about something like that,” he adds. Even on a less-intense level, Christ Church has been the victim of more mundane crimes, including the vandalizing of an air-conditioning unit last year.

“We are pretty accessible,” Vaughn says, but “I think my staff is really good at keeping an eye on things.”

In a quest for greater security, some houses of worship have hired armed security guards. That’s a line Vaughn doesn’t plan to cross.

“I’ve got guys who work for me who are very street smart, but they will never be armed,” he says. “And I don’t care what the (state) Legislature says: We’ll never have weapons on the property.”

Dr. Aslam Abdullah, director of the Islamic Society of Nevada, says the society’s mosque has, at times, been the target of theft and vandalism and the society has received “threatening” messages on its answering machine.

So far, the mosque has escaped serious problems, Abdullah says, despite a schedule that keeps it open from morning prayers (which begin at about 4:30 a.m.) to evening prayers and activities that currently run until about 10 p.m.

Now, during Ramadan, the mosque is open 24 hours, “because we do not prevent people from coming to the mosque at any time to pray,” Abdullah says.

The society’s security measures include cameras positioned around the property and worshippers who keep an eye on activities during prayer services. Also, Abdullah praises the Metropolitan Police Department, which keeps clergy apprised of anything that potentially could affect worshippers’ safety.

“When we have one of these incidents that take place anywhere in the country or anywhere in the world, our police department is one of the first ones to reach us and they alert us about it,” Abdullah says, usually following up by increasing police presence in the area.

Since the Charleston shootings, a lot of people have asked me questions, Abdullah says. But, ultimately, “we can only do this much, because, after all, the purpose of worship and a place of God is to let them be available to people at any time.”

So the measures that can be taken are taken, “and then we leave the matter in the hands of God,” Abdullah says.

“We know that sounds a bit theological, but this is what I think almost all faiths would say,” Abdullah says. “They can do certain things up to certain things, but then we leave the matter to God.”

Rabbi Shea Harlig of Chabad of Southern Nevada says comfortably balancing security and a welcoming environment can be difficult.

Harlig notes that Chabad often is a target for terrorists around the world, and an attack on a Chabad facility in India in 2008 left several people dead. So, he says, different rabbis likely will opt for different security measures, and some may increase security only during such times as High Holy Days.

In the United States, “we generally err on the side of being more open, rather than tighter security,” he says.

“I know if you go to a synagogue in Europe and they don’t know you, you have to register in advance. You have to bring a passport,” he says, and he has encountered European visitors to Las Vegas who asked if they needed to register to attend a service here.

“I think what you really have to do is balance the situation,” Harlig says.

The Rev. Dennis Hutson, pastor of Advent United Methodist Church, says he felt his calling to the ministry when he was 10 years old and watched the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. in the March on Washington. Even then, Hutson says he had a feeling that King would die for his beliefs and that, if he were to pursue his own calling, that might someday be true for him, too.

Hutson views incidents such as the Charleston shootings through that lens.

“We are here to support the community as well as our congregation,” he says, so “people are always welcome to come in and be a part.

“The church is a spiritual institution and we rely on God’s protection.”

Not that simple prudence isn’t also in order.

“I retired from the Air Force as a chaplain and the military teaches you to be vigilant,” Hutson says. “So we just live in a time when Americans can no longer walk around assuming that everything is fine. We must always be aware.”

Contact reporter John Przybys at jprzybys@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0280 or follow @JJPrzybys on Twitter.