Ramadan fast presents extra challenges in extreme desert heat

Barely in the door, this stranger is assaulted … with kindness. Plus watermelon, dates, milk, salad, vegetables and meats.

“Have you had something to eat?”

“Please, have some food.”

“We have so much, you must try it.”

“Here, take this.”

Following evening prayers, this nightly feast is going on inside a long hall, set up cafeteria-style, adjoining the Jamia Masjid mosque at 4730 E. Desert Inn Road.

Warm and smiling while ladling aromatic soups and stews out of aluminum trays and into paper bowls and plates, Las Vegas Muslims wrap up another day of food and water deprivation with a nightly communal meal — nearly three weeks of sunrise-to-sunset fasting as of this recent night.

Tomorrow, once again, they will forfeit sustenance and hydration for another 15 hours as the city roasts like burnt sirloin.

Ramadan, the Islamic holy month, requires it — triple-digit desert temps notwithstanding. Why comply? Ask tobacco shop owner Najib Jabarkhil and get a very on-point reply.

“The heat we are facing in Las Vegas, compared to the heat of hell, we cannot even imagine how tough that will be,” Jabarkhil says. “As you are making your way up to heaven, it is not easy or cheap. If you are struggling but you are in the way of God, I am pretty sure you are getting a lot of help.”

Observed during the ninth month of the Islamic lunar calendar — this year it began June 17 and concludes July 17 — Ramadan is celebrated as the time Allah first revealed the Islamic holy book, the Quran, to the Prophet Muhammad. With abstaining from smoking and other unhealthful habits, and from hurtful behavior toward others, Muslims’ major obligation is daily daytime fasting, a daunting challenge amid Las Vegas summers that would make furnaces envious.

“It’s extremely difficult for those who are aged or youngsters or those who are working in the open air, but this is the physical endurance they have developed. It’s just like the NFL preseason, where the players go through a rigorous exercise,” says Dr. Aslam Abdullah, director of the Islamic Society of Nevada, which is based at Jamia Masjid, the city’s largest mosque.

Though not drinking in this heat and risking dehydration can be difficult, observant Muslims can cool off by taking cold showers, splashing water on their face and bodies, idling with their feet in cold water and even soaking their clothes.

“But you are not supposed to hurt the gift of health that has been given to you,” Abdullah says. “We have many medical professionals in the (Muslim) community who conduct workshops before the fasting and inform people and make recommendations. There are diabetes patients who want to fast, but around 3 or 4 o’clock, their sugar level starts coming down, so that is a crucial moment. Sometimes they have called us asking to break the fast.”

Others refuse to be derailed by it. Diabetes afflicts Khalid Khan, president of the Islamic Society of Nevada. “My doctor advised me not to fast, and around noontime my sugar would drop so much that I could not physically move around,” Khan says. Yet he rearranges his daily routine to accommodate the fast. After 2 p.m. each day, he stays home, refraining from physical activity. “I relax because I don’t have any strength left in my body,” he says.

Don’t friends and family scold him for endangering his health, especially when allowances can be made for medical conditions? “Every day,” he says. “But after the fast, I feel good because I get spiritual strength.”

Such dedication under difficult circumstances is far from uncommon. “My husband, who passed away last year from cancer, was a physician himself,” Dr. Saleha Baig says. “He was also diabetic, and his father, who was 94 when he died, they were both fasting almost to the end.”

Wearing shorts and the traditional kufi headwear, Ali Monti Ciski busies himself sprinting between the kitchen and the hall, helping to serve food and clean up, as an accommodation for not fasting. Islam allows those who cannot fast during Ramadan other options, including fasting at another time, feeding others and performing charity.

“The heat is too extreme, and with the medications I take, I’d pass out,” says Ciski, who converted to Islam nine years ago. Early in his conversion, he worked in an air-conditioned building and fasted, but a few years ago, after doing manual labor at Excalibur during Ramadan, he found he couldn’t endure it.

“You feel guilt because you feel you’re not part of the team,” Ciski says. “Fasting is supposed to bring you closer to God and gives you humility when you see people in Africa suffering and dying. Starving to death would have to be one of the worst deaths.”

Empathy is also motivation for Tammy Cochran, a former Lutheran who also goes by the Arabic name of Khajeda. “My mouth gets cottony, but it makes you aware of the ones who are not able to drink, and it breaks your heart,” she says. “You know how it feels. That is why we fast, to remind us. And Allah made it easy for me. I quit smoking and I quit drinking.”

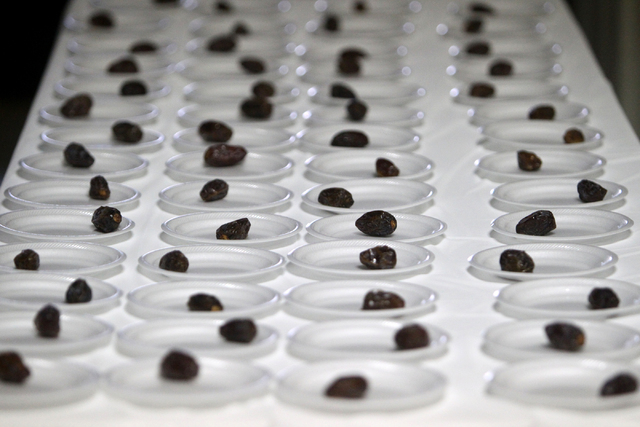

Traditionally, the fast is broken each evening with only a light snack such as the one served at Jamia Masjid — dates, a small slice of watermelon and cup of milk mixed with Rooh-Afza, a syrup popular in Pakistan, which gives the milk a pink hue. (Predawn meals are also light — usually eggs or cereal with tea or coffee.) After evening prayers, the larger meal is enjoyed.

While worshippers have always brought food to share, Abdullah says he has noticed that where once it was “greasy and heavy,” it has now shifted toward more salads, soups and baked, rather than fried foods. On this night, the menu also included potatoes, beef with green peas, and lamb and vegetable stews.

“People are heeding the advice of nutritionists and medical professionals,” Abdullah says. And rising awareness of unhealthy eating habits has made not eating the next day easier.

“Food makes you tired, especially the candy and doughnuts. We don’t eat proper food in the workplace, so food can be an enemy,” Baig says. “The fasting energizes you. The whole year you eat. You have one month where the internal system becomes a purification of not only the physical part of you, but the spiritual aspect. Also, the body needs rest. It puts in too much bad stuff, so it rejuvenates itself to be ready for the next 11 months.”

Ultimately, though, local Muslims view fasting — even under the intense sunrays of Las Vegas — as a divine communion. “When you are fasting, God gives you the courage and the will to continue,” worshipper Amanullah Naqshband says. “This is between you and God.”