Air Force pilots honor their comrade and supporter

He wasn’t an Air Force pilot. Never was stationed at Nellis Air Force Base. Hadn’t been in the military since his Navy days during the ’50s.

But to a generation or two of U.S. Air Force pilots flying out of Nellis, Evan Thompson was a brother in arms as beloved as any with whom they served, even if most of them knew him only from a distance.

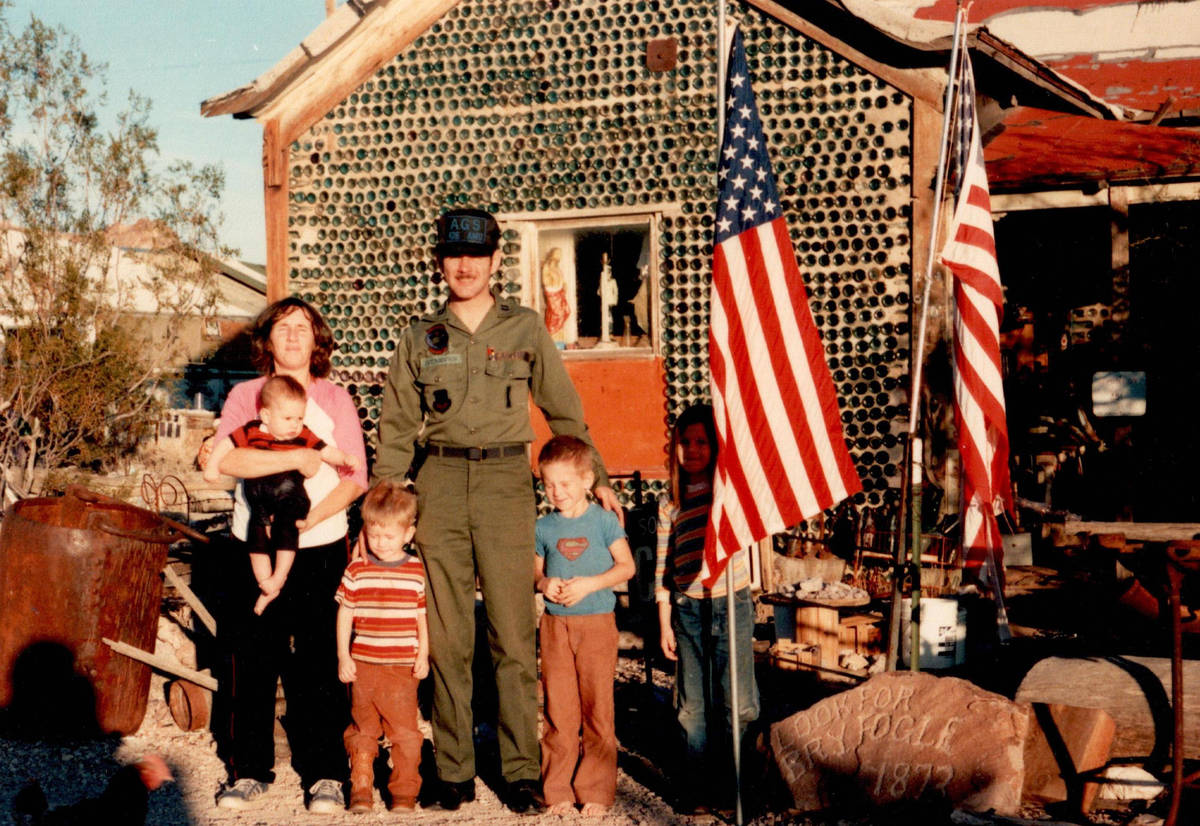

For decades, whenever he heard a military aircraft or fighter jet from Nellis streaking over his home north of Beatty, on the edge of the Nellis range, Thompson would run out to greet them, waving a giant American flag — often accompanied by his wife and kids.

And just like the fighter jockeys with their own call signs — Evil, Mongo, Scud — Thompson came to know, pilots bestowed on Thompson a nickname of their own.

“The Real American.”

Second nature

“Patriotism is a word that gets thrown around all the time,” says Lt. Col. Tony Roe, who first flew over Thompson’s house during the late ’90s. But for Thompson and his family, patriotism was “like second nature for them. Unfortunately, we don’t see a lot of that these days.”

On Oct. 2, Evan William Thompson III , 83, died of cancer in a Las Vegas care facility. On Saturday, family, friends and pilots paid tribute to him during a memorial service at Beatty Community Center. On Sunday, they assembled at Thompson’s home for a final, fitting act of gratitude: a flyover by four A-10 aircraft from Nellis.

Thompson, who was born in Seattle, was raised from age 1 by his grandparents. “They were old vaudeville, circus people,” daughter Eirianedd Oser says. “By the time my dad was 12, he had visited all over the lower 48 states.”

Thompson joined the U.S. Navy in 1955. He served for four years and moved to Beatty, where he was a miner at the Nevada National Security Site and ran small businesses. He retired 20 years ago.

Oser suspects her father’s military experience fueled his patriotism. So did the tenor of the ’60s and ’70s.

“He saw a lot of political things happening in the country at the time,” Oser says. “One day, he decided he was going to start to go out and wave the flag to say, ‘I support you guys.’ It took off from there and word got around.”

Marc Frith visited Thompson in 1983 while serving as an A-10 pilot at Nellis. He remembers how Thompson’s home would come alive “with the arsenal of red, white and blue as Evan and family members would dash from his home proudly waving Old Glory as we passed by, and fuel remaining, execute a cross turn for another pass.”

Through word of mouth, Thompson’s home became “the go-to place” for pilots exiting Nellis’ northwest ranges on the way back to base. Fellow A-10 pilot Chris Beckman learned about Thompson in 1996 from Frith, then his squadron commander.

“It was like it kind of got passed down from pilot to pilot,” says Beckman, who was attending his first Red Flag exercise at Nellis. The day before exercises began, while relaxing at the hotel pool, Beckman recalls, Frith said, “Let me tell you a story about a legend in these parts …”

Later that week, while flying his A-10 over Thompson’s home, “out comes this man running as fast as he could in blue overalls,” Beckman says. “He was just waving that flag, and sure enough, out comes five or six or seven of his family members.

“My head is against the canopy going, ‘Who is this guy? He’s got to be a kook.’ Then I say, ‘I’ve gotta meet this guy.’ ”

Meeting a legend

Like Frith before him, Beckman passed on to younger pilots the story of The Real American. “Everyone has the same reaction — disbelief, admiration and pride. This man was showing us his sign of respect and appreciation that what we were doing was a dangerous job.”

In 2001, while attending a six-month-long fighter weapons school course at Nellis, Beckman, Roe and a fellow A-10 pilot packed a cooler and drove to Beatty to meet Thompson in person. They stopped at a casino in Beatty and asked a bartender if anybody knew where he lived. The bartender gestured to a man sitting next to Beckman.

“Well, that’s his son sitting right next to you, so I’m sure he can help you,’ ” the bartender said. Following Thompson’s son, the group drove to the ranch, where Beckman noticed about a dozen giant American flags rolled up and leaning against a wall, ready for unfurling.

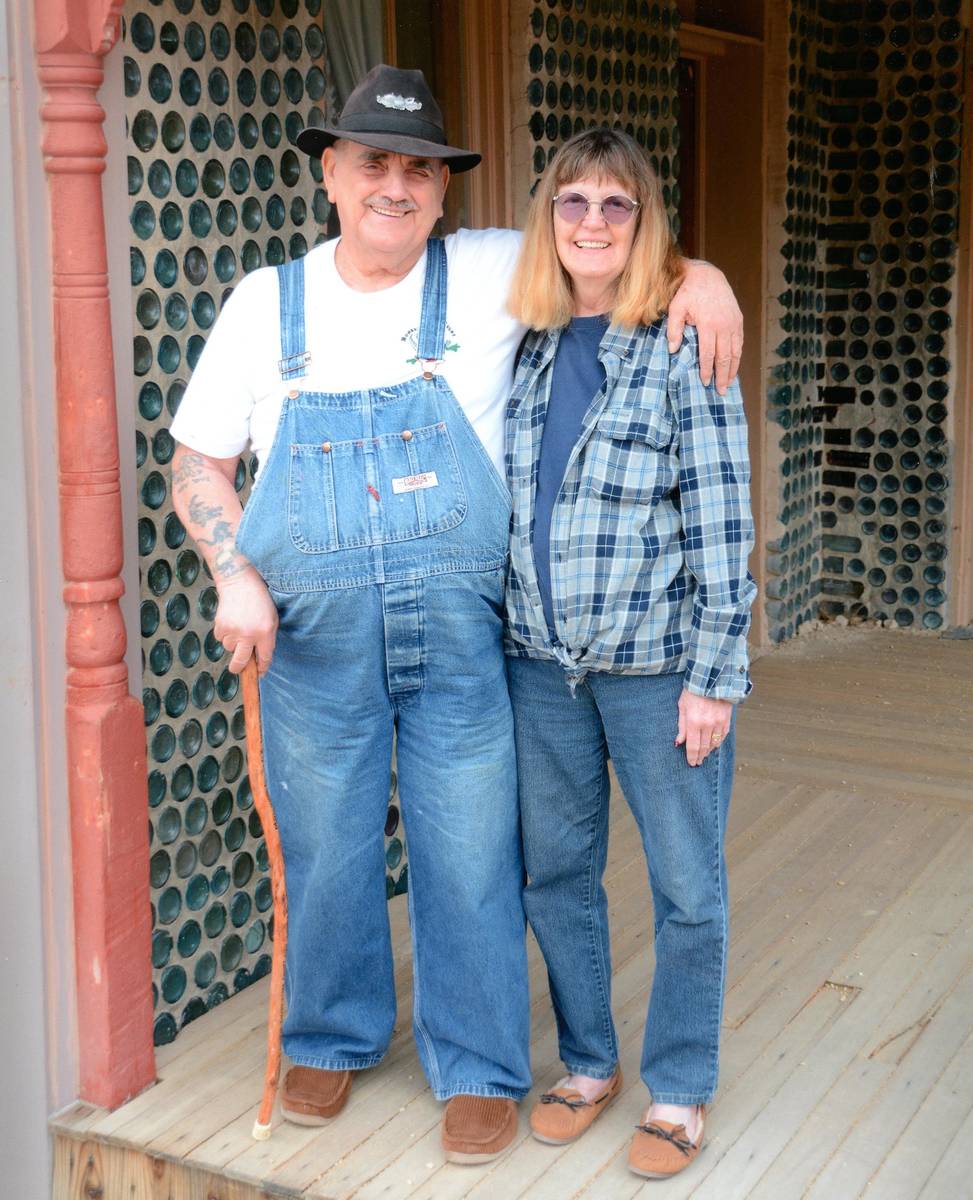

“Out comes this man, super-humble. He gave us a big bear hug,” Beckman says. “He was one of the most warm, affectionate, articulate men I’ve ever met. Extremely smart. He made you feel right at home.”

Roe — who still flies A-10s in the Air Force Reserves — remembers that Thompson “had huge scrapbooks with all these pictures of people who had visited. He had been down to Nellis as a VIP and had a picture of him sitting in an A-10 with Marc Frith.”

Frith remembers that during his own first visit, Thompson stopped talking midsentence when he detected a familiar sound.

“It was like my dog’s ears popping up,” Frith says. “He was running for the door. We grabbed a couple of flags, and a pair of Viper F-16s went right by us.”

After their meeting, Beckman and Roe invited Thompson and his family to attend their black-tie weapons school graduation banquet where, Roe says, “it was immediately apparent to us he was a legit VIP at Nellis to some of the people who had been there longer than us.”

At that event, Beckman recalls, Thompson received a standing ovation when his name was announced as a visiting dignitary, and a second ovation when his name was mentioned in remarks by the general who was the night’s keynote speaker.

Thompson’s house was such a popular flyover destination among pilots that, for a time, it was marked on maps with a red dot, Frith says. “That means, don’t fly there. It was a noise-sensitive area. I guess one of his neighbors complained.”

That didn’t end the friendly sorties, Frith adds. In Nellis’ fighter community, Thompson was “a true legend.”

Honoring a friend

Michael Curley, who retired as an A-10 Operations Group Commander last year, says he considered it “my duty” to introduce young pilots to “this unbelievable patriotic experience.”

Curley would fly by Thompson’s home a few times a year while training at Nellis. He always was amazed at Thompson’s dedication.

“Every time we’d go by his property he’d be out,” Curley says. “It seemed he’d muster whatever family he could and be out in the driveway waving giant flags. So I got the chance to pass that on to all the new fighter pilots and show them what I think is a national treasure.”

Oser says that her father broke his hip last year. Then came a diagnosis of bone cancer. Beckman says that when word got out to the fighter pilot community, and COVID-19 restrictions prevented visitors from seeing him in a Las Vegas health care facility, pilots targeted Thompson with “an outpouring of love” through cards, letters and phone calls.

On Oct. 2, Thompson died. Beckman organized a GoFundMe campaign (gofundme.com/f/evan-thompson-the-real-american) to help with medical expenses. That money now will go to the family for a memorial and philanthropic efforts.

Frith spoke with Thompson on the phone before he died. His message was simple but heartfelt.

“I just wanted to let him know how much we appreciated him as a patriot and a supporter,” Frith says.

Thompson “symbolizes everything we fighter pilots trained and fought for. His simple gesture of waving flags as we flew by was felt strong in our hearts.”

Contact John Przybys at jprzybys@reviewjournal.com. Follow @JJPrzybys on Twitter.