Member of UNLV’s Special Collections is only book conservator in Nevada

The word unique gets tossed around without much attention toward its meaning. It doesn’t mean merely rare or unusual. It means singular.

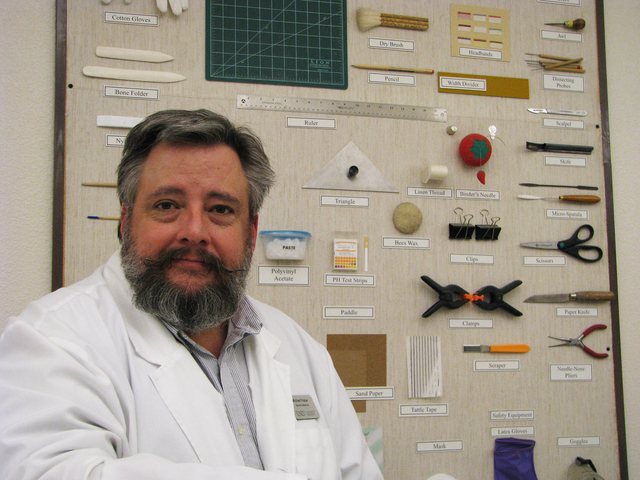

In Nevada, Michael Frazier is unique.

“I have a staff of work-study students and I’m part of a much larger team of technical services at UNLV Special Collections,” he said, “but if you’re talking about hands-on book repair and being an institutional conservator, I’m the only one in Nevada.”

Only a handful of people nationwide do what he does, and the lion’s share of them work at places such as Harvard University and the National Archives in Washington, D.C. Frazier knows of one in Utah and a few in California.

“There is a lab similar to this one in Carson City at the state archives, but they were never able to get the funding to staff it,” he said.

Michelle Light, director of UNLV Libraries Special Collections, said Frazier’s workspace is one of the places where the staff takes potential donors.

“We can show the kind of commitment we have to stewarding the history of Southern Nevada,” Light said. “It shows the investment we put in trying to extend the life of our materials.”

While Frazier’s office is in Special Collections, he is concerned with all of the books in the library.

He is responsible for keeping the books safe and repairing books that cannot be easily replaced. He usesa combination of state-of-the-art tools, chemical science and hand tools that haven’t changed in centuries.

“My job involves preservation and conservation,” he said. “In preservation, we concern ourselves with the collection as a whole, and in conservation we concern ourselves with how we service a single item.”

Preservation includes security and environmental monitoring — including tracking and controlling temperature and humidity. Insects also can be a concern.

Conservation includes a range of things such as simply repairing a tear in the cover with archival library tape, running library paste along the spine or tearing apart a ragged book and rebuilding it. The latter is where the hand tools come into play.

“A lot of libraries have book-repair units to make the books last a little longer and make it through to the next round of a budget,” Frazier said. “We’re different with our research library because we’re trying to make things last a lot longer. We may be going for decades or maybe a century.”

There is a complex balance deciding if a worn book should be replaced or if it is less expensive to repair it. In the case of many of the books, replacing them may no longer be an option.

Frazier pulled a book out of a group waiting to be repaired that had its spine mostly detached and another from a recently repaired group that was in similar shape. He removed the old spine and created a new one, matching the original color as closely as possible. He has a small rainbow of colored cloths and tapes at his disposal.

“Everything we use is archivally sound,” Frazier said. “We’re not skimping.”

After everything had been restitched, tightened, repasted and pressed in a large heavy-book press, the new spine was attached. Had the old spine been completely detached and lost, Frazier has a small press designed to hot-press foil into debossed text.

One book in his “to do” group had a marbled cover that was heavily worn. Frazier has learned the centuries-old art of paper marbling, in which paint is floated on the surface of a solution and intricate patterns are created.

“You come in with a marbling brush and make various designs and run combs through it to create the pattern, then you dip the paper into it,” Frazier said. “I try to match the pattern on the original book as closely as possible. It’s not easy, but it helps with the aesthetics of the book. I don’t use it often, but it does highlight the level of work we do here.”

To reach East Valley View reporter F. Andrew Taylor, email ataylor@viewnews.com or call 702-380-4532.