Schools set to help students who fell behind during pandemic

As more than 300,000 students head back to Clark County School District classrooms Monday, schools are gearing up to help children who may have fallen behind academically during the COVID-19 pandemic.

A new school year begins with full-time in-person classes for all grade levels, as well as distance learning options — a change from a year ago when all classes were taught remotely.

The pandemic made an impact academically on students, with some students behind in subject areas such as English and math, and more students logging failing grades. Educators say they’re focusing not only on filling the gaps but on helping students with their social-emotional health.

“I think overall we know across the board that there are going to be some gaps,” said Vicki Kreidel, president of the National Education Association of Southern Nevada and a second-grade teacher in Las Vegas. “That’s just common sense.”

Kreidel said she has seen students who have been through trauma during the pandemic, including getting sick with COVID-19, having family members who died or parents who were out of work.

Instead of focusing on learning loss, she said, “I personally think as educators we should focus on student emotional well-being,” including building relationships with them and making them feel safe at school.

Nationwide, there is a narrative about pandemic “learning loss,” but that’s not what the data shows, said Megan Kuhfeld, senior research scientist at NWEA, a Portland, Oregon-based nonprofit that has developed school assessments such as Measures of Academic Progress (MAP).

“Kids are making gains,” she said. “When you compare them to the pre-pandemic normal of what learning gains look like, that’s where the declines are.”

Most children advanced to the next grade level, but some may be behind and may not have covered all of the previous year’s materials, Kuhfeld said.

The question going into this school year, she said, becomes: How do we catch them up?

What national research shows

Nationwide, data from 5.5 million students in third through eighth grades who took MAP Growth assessments last school year showed children took a hit in math and reading by spring, Kuhfeld said.

She is one of the authors of a July research brief, “Learning during COVID-19: Reading and math achievement in the 2020-2021 school year.”

Data shows students made academic gains but at a lower rate than where students would normally be pre-pandemic, Kuhfeld said, noting math was particularly affected.

On top of that, students of color and those who attend high-poverty schools were more affected on top of already-existing inequities, she said.

Kuhfeld said she doesn’t have a good answer yet for what role distance education versus in-person classes played in scores.

But an analysis released in July by management consulting firm McKinsey &Co. concluded U.S. students were an average of four months behind in reading and five months behind in math by the end of last school year.

The gap was wider in majority-Black and low-income schools, according to the paper.

The report also estimated students may earn between $49,000 and $61,000 less over their lifetime if steps aren’t taken to remediate “unfinished learning” as a result of the pandemic.

In Clark County, school district students in kindergarten through ninth grades take the English language arts and math MAP assessments. Third through eighth graders also take a science test.

The district released data showing the percentage of students who met targets last school year — from fall to winter and winter to spring.

The district, though, didn’t provide a requested breakdown by student ethnicity or a comparison with previous school years by deadline.

For elementary school students, 35 to 40 percent met targets in math and reading last school year, depending on the test and testing cycle. Between 42 and 47 percent of middle schoolers met their targets, while 44 to 51 percent of high schoolers did.

Kreidel said last week that MAP scores from last school year aren’t accurate. “I can guarantee it.”

Among her second graders, she encountered multiple instances of parents helping their children with the tests. One student who she knew was struggling received the highest reading score in the class.

Some students were experiencing technology issues and kept getting logged out during the test, Kreidel said, and there were many distractions at home during distance learning.

“I don’t believe that most students could focus on the test,” she said.

Grades suffered in spring semester

During spring semester, grades took a hit across the Clark County School District, with 44 percent of students logging at least one D and 39 percent with at least one F.

That’s significantly higher than the 2019-20 school year, when 34 percent of students had at least one D and 22 percent had at least one F.

The school district provided the data in response to a Review-Journal request.

Middle school students appeared to struggle the most with grades, with 55 percent getting at least one D and 51 percent at least one F.

There was also a major gap between demographic subgroups — a trend in previous school years too.

Nearly 53 percent of Black students had at least one D on their record, and 50 percent had at least one F during spring semester. About 50 percent of Hispanic students had at least one D, and 46 percent had an F.

That compares with 32 percent of white students with a D and 25 percent with an F. And 27 percent of Asian students had at least one D, and 21 percent had an F.

School district officials declined interview requests to discuss students’ scores or grades and issued a statement Thursday to the Review-Journal.

“The pandemic impacted our entire community in ways that no one could plan for, and certainly in ways that no one could have predicted,” the statement read.

“We have long acknowledged that there will be learning loss and an impact on students’ grades and assessments,” the district said. “These issues are not exclusive to our District but have been experienced nationally as students and educators were forced to make an overnight shift to distance education.

“As we work to emerge and recover from the pandemic, the District is committed to ensuring that our students are re-engaged with school to be college and career ready upon graduating high school,” the statement said.

Helping students catch up

Helping students who may have fallen behind is an area where Desert Pines High School in Las Vegas has years of experience.

Desert Pines was designated as a “turnaround school” in 2015 by the school district, which spurred it to receive extra resources with the goal of improving student achievement, including graduation rates.

“Right now for us, we have the systems or the opportunities for students to get their credits,” Principal Isaac Stein said. “The thing is our numbers are just going to be greater than they were in past years.”

Some reasons Desert Pines students may have fallen behind during the pandemic include being a caretaker to younger siblings or working to help provide for their family, Stein said. “They took on more than just going to school.”

And some may have faced Internet connectivity challenges, he said, although the school made sure to provide laptop computers to students and work with Cox Communications on Internet access.

For the new school year, Desert Pines officials put together a plan seeking an extended school day, Stein said, but whether it will be implemented will depend on funding.

The school, which will have approximately 3,300 students, is among about a dozen in the district that is providing a full-time distance learning option this school year.

Three weeks ago, there was little interest in distance learning among school families, Stein said. “With the (COVID-19) delta variant, it’s starting to increase.”

Now, about 200 students are slated to participate. Stein said the school is looking at whether it can accommodate more, but the offering may be at capacity.

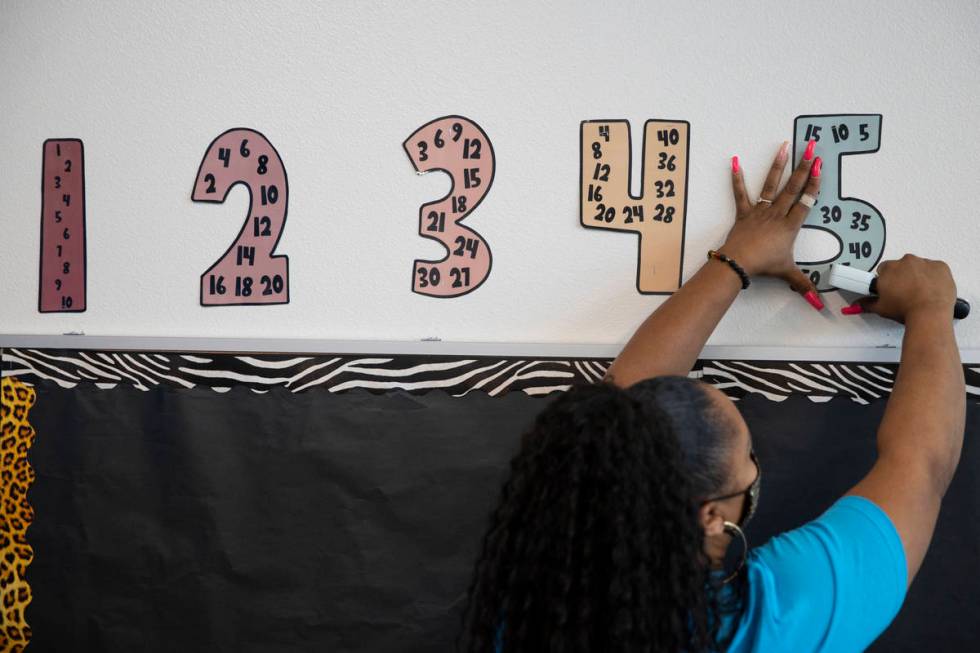

At Tate Elementary School in Las Vegas, “a lot of students typically come in below grade level and we need to provide them with the support and structures to meet grade-level standards,” Principal Sarah Popek said.

She said teachers are equipped to help address those gaps. Because of the pandemic, “we’re probably going to be looking at a wider gap than in years past.”

During distance learning and in-person instruction, some students attended class every day, Popek said. “On the other extreme, we had students who never logged in or rarely logged in despite our outreach and our support.”

At McCaw STEAM Academy in downtown Henderson, the focus is on building relationships with students, their families and employees, Principal Jennifer Furman-Born said in a Thursday email to the Review-Journal.

That’s necessary to “work past the panic of returning to school and the pandemic,” Furman-Born said. “Once we have regained trust, it will be working to build that learning stamina.”

Going into a new school year, there will be academic gaps and children who need a little extra help, Furman-Born said.

“But that’s our job, and that’s normal, even if we were not going through a pandemic,” she said.

Contact Julie Wootton-Greener at jgreener@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-2921. Follow @julieswootton on Twitter.