New book tells of Father James Groppi’s efforts to end discrimination

You’re a kid who knows right from wrong.

When you were little, your parents helped you understand what was good and what was not. Once you got bigger, you could see when something wasn’t fair and you remember how much you hated that.

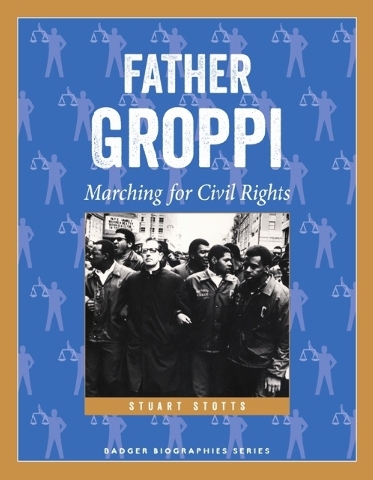

These days, you’re old enough (and strong enough) to speak up when you see things that are wrong. In the new book “Father Groppi: Marching for Civil Rights” by Stuart Stotts, you’ll read about one peace-loving man who did, too.

James Groppi didn’t know much about civil rights when he was a kid, but he knew what discrimination felt like. Born in 1930, Groppi was the second-youngest child of parents who came from Italy — and in segregated Milwaukee that meant a lot of teasing and prejudice.

But the Groppi family was close. The parents taught tolerance, and James was a good scholar. Teachers also noticed that he was a natural leader, and he became captain of his basketball team. It was during a game that he had one of his most memorable moments: James blocked another player who happened to be black, and accidentally knocked him down. The boy kicked James, and when they both apologized later, James understood that it was an example of respect.

In 1952, James went into the seminary to study for the Catholic priesthood. He worked at a Milwaukee youth center, where he got to know many African-American children, and he saw how much racism hurt them. When he graduated from seminary and was ordained in 1959, he preached against discrimination at an all-white church before he was sent to a parish in which the congregation was almost all black.

That move gave him an early understanding of civil rights.

Starting in 1961, Groppi got involved in the Civil Rights Movement. He made several trips to the South, where segregation was nearly everywhere. He worked to integrate restaurants, and he supported Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s third march on Selma . He was arrested for peaceful protests, and he kept supporters safe on many marches.

And then, in action that would put him in the national news, Father Groppi took on the entire city of Milwaukee over unfair housing practices.

I’m always a little surprised when the work of an influential person is lost to history. Why don’t more people know this story? Fortunately for your child, “Father Groppi: Marching for Civil Rights” corrects that omission.

But Stotts doesn’t just tell the tale of Groppi, his work and his disappointments. Stotts also writes about how Catholic higher-ups viewed Civil Rights, where racism came from and what happened, and he tells the story of a city that he claims is still “deeply segregated.” This is a fascinating biography, made better for kids because of a glossary, index and pronunciation guide.

If your child loves history, or if you want him to know more about the hard work done for equality, here’s a book to find. For your 7- to 12-year-old, reading “Father Groppi: Marching for Civil Rights” seems just right.

View publishes Terri Schlichenmeyer’s reviews of children’s book weekly.