‘A medical wasteland’: east Las Vegas community nears 10K COVID cases

As the scourge of COVID-19 has swept across Nevada, one east Las Vegas community has experienced the worst of it.

Nearly 10,000 cases of the disease caused by the new coronavirus have been reported in the 89110 ZIP code, an area roughly bounded by East Owens Avenue to the north, North Pecos Avenue to the west, East Charleston Boulevard to the south and Los Feliz Street to the east.

The 9,796 cases reported through Friday among residents of the area are 2,653 more than the number in the second-highest Las Vegas Valley ZIP code, 89108 in the northwest Las Vegas Valley, which had reported 7,143 cases.

The area has a majority Hispanic population, nearly 54 percent, compared with 33 percent in the city overall, according to 2019 data from the U.S. Census Bureau. That helps explain why the disease has run rampant in the area, which encompasses Eldorado and Desert Pines high schools and the Sunrise Library, as Latinos have been hit especially hard by the virus.

The 89110 ZIP code is also home to more than 70,000 residents, making it one of the most densely populated areas in the county, and has many working-class residents and multi-generational families living in one home, said Dr. Fermin Leguen, acting chief health officer at the Southern Nevada Health District.

“Many of the people in that area, their occupation makes them more exposed to the virus because they’re working in service industry or jobs where they’re highly exposed,” Leguen said. “They don’t have the opportunity, as (those) in other ZIP codes, to work from home or work limited hours.”

‘A medical wasteland’

Guy Girardin, president of Puentes (“Bridges” in Spanish), a nonprofit that connects Latinos with health and social services, said language barriers and lack of access to health care also have contributed to the spike in cases in the area, part of Sunrise Manor. The nearest testing site for 89110 residents is outside the ZIP code, at Cashman Center, a 20-minute drive or a very long bus ride away.

“It’s a medical wasteland,” Girardin said. “You can’t not treat 20 percent of the population and think you’re going to end the pandemic. You just can’t.”

Leguen said in August that reaching Latinos after they tested positive is a challenge because of the language barrier. The district has since hired 300 more Spanish speakers and is working with UNLV to help do contact tracing in the community.

“For many people, they don’t have that many protections,” Leguen said. “They are not paid if they don’t work, so it’s a very tough decision for them. But they have to concede they could get sick themselves and transmit it.”

“If you are with any symptoms,” he added, “please assume that you have COVID and don’t go back to work.”

Las Vegas City Councilwoman Olivia Diaz, whose ward includes the 89110 ZIP code, joined local officials in a campaign called Está en Tus Manos to build trust with the local communities and encourage residents to get tested.

Building trust

“The campaign builds trust with the Latino community by establishing presence not only via traditional media such as television, radio and direct mail, but also on the ground at supermarkets, small businesses, unions, local consulates, food distribution sites (and) church groups,” Diaz said in a written statement.

Diaz said she and others are working especially hard to get the word out about the urgency of getting vaccinated.

“Many people in these communities are hesitant to get the vaccine,” Girardin said. “In order to work in communities that are marginalized, you don’t try to convince people to get the vaccine through social media or billboards. You have to get into the community and build trust and rapport with them in person.”

Puentes and its partners Three Square and Mater Academy, a K-12 public charter school near the western border of 89110, host a monthly resource fair to provide medical resources and food to area families.

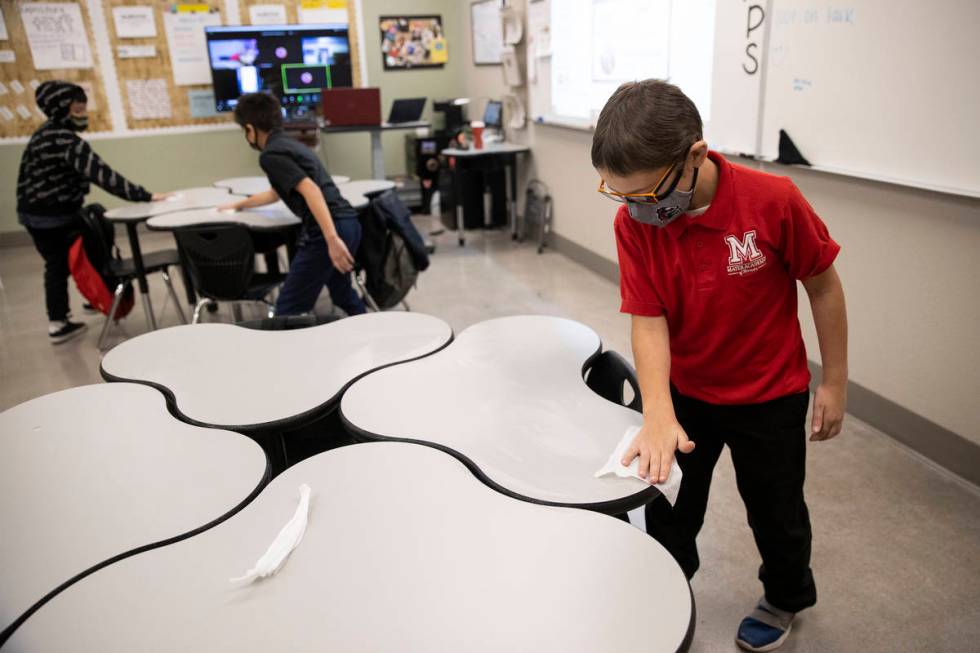

Mater Academy also strives to build awareness of the disease among its students, whether they attend in person or take online classes. Those who attend the school clean their desks at the end of the day and walk through halls and rooms with COVID-19 air purifiers that puff out steam to kill viruses circulating in the air.

Even so, school nurse Kenia Delatorre said she sees anywhere from 15 to 25 students in a typical week for COVID-19 assessments.

She didn’t have to think long when asked whether she’s seen COVID-19 ravage entire families.

Her co-worker Angie Leyva, a mother of four who lives with her 63-year-old mother, said all but one of her family members caught the disease within a month before the school year started. She said she had no idea how the virus got into their home.

Delatorre said she sees many families in similar circumstances.

School’s supporting role

“A lot of our school, most of them need food for lunch, and the families are affected. A lot of them have lost their jobs, and under those circumstances the school opens up,” Delatorre said. “It’s a different environment for them, and they’re open to coming to school instead of being at home and working virtually, which makes it tremendously hard for them.”

Molly Garcia, 60, a retiree who lives in the area, said all nine members of her household got COVID-19 in November, leaving the whole family out of work for three weeks. She suspects that a family member may have been infected during a shopping trip or at work.

“It was hard for a while. We barely had food,” Garcia said last week. “Even when my son was feeling sick, we’d still sent him to the grocery store to get food for us. There was no one else to do it.”

Principal Renee Fairless said combatting misinformation and distrust is key if authorities are going to stop the spread. She said the school recently had a parent of three students who was fighting for her life while on a ventilator at the same time other parents were questioning why they’d need to wear a mask to visit the school.

“We know this is the highest rate in the state, so education is a big key,” Fairless said. “These are the things that really work. Wearing a mask is not fake. It’s real.”

Girardin, the leader of the Puentes nonprofit, said the other big need exposed by the pandemic is the correction of inequities in the community.

“If there’s any good to COVID-19, it has revealed a lot of cracks in our health care system and what’s wrong with what’s going on,” he said. “Now, it’s up to everyone to look at that and say, ‘OK, we got to fix this going forward’.”

Contact Mya Constantino at mconstantino@reviewjournal.com Follow @searchingformya on Twitter. Contact Sabrina Schnur at sschnur@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0278. Follow @sabrina_schnur on Twitter.