Ex-UNLV professor heard America was on the moon before most of US

William Corney heard Neil Armstrong say “The Eagle has landed” a second or two before the rest of the world learned the United States had put a man on the moon.

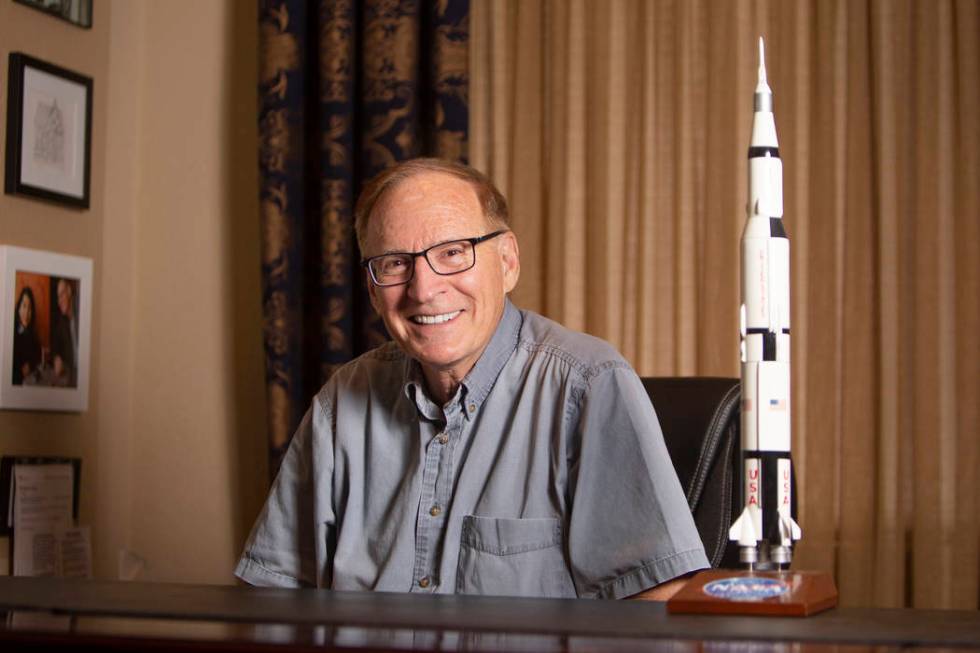

That’s because the 76-year-old retired UNLV business professor was working for a NASA subcontractor when the Apollo 11 mission landed on the moon 50 years ago Saturday.

Stationed in the middle of the South Atlantic, his communications station was the first to pick up the transmission from the landing craft that it had touched down safely on the moon’s surface.

The room was tense leading up to Armstrong’s transmission, and an elated cheer broke out when word of the safe landing was received.

“One guy jumped up on top of his desk,” Corney recalled this week. “When it actually landed and we said ‘OK, they made it,’ everybody was shouting.

“It was really a proud moment. For many, many years after that, people had some pride that we could do things nobody else could do.”

One of the ‘invisible people’

Though always interested in science, Corney said he never gave space much thought until high school, when “the big thing people were talking about was rockets.”

His fascination led him to earn a degree in electrical engineering from the University of Michigan in 1964 and enabled him to land a job with the Bendix Field Engineering Corp., a subcontractor of NASA.

At the time of the Apollo 11 flight, he was 26, and one of the youngest members of a team stationed on Ascension Island, a small volcanic island in the south Atlantic Ocean.

Depictions of the Apollo 11 mission often focus on the control room and the astronauts who made the trip, but Corney said little attention has been paid to the “invisible people” who made the mission possible.

Corney said he worked in downrange stations spread around the globe, each of which had 30-foot and 82-foot antennae to facilitate communication between Mission Control and the astronauts — Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins.

Technicians at the stations — known as “range rats” — picked up transmissions and relayed them to the control room in Houston. Whenever the spacecraft was in range of the Ascension Island station, Corney and other engineers also kept track of the astronauts’ vital signs, the rocket’s location, on-board operations and other data. He and his colleagues often slept on cots in the office when the spacecraft was in range to ensure that they never missed a transmission from the astronauts.

Though isolated on a sparsely populated island nearly 6,000 miles from the Space Center Houston control room, Corney said he never felt far from the mission.

“Everybody had a connection with it that worked on it,” Corney said.

Landing at UNLV

Corney also worked on the Apollo 12 mission, which also landed astronauts on the moon, before the Apollo program was shut down and future missions canceled in 1975. He blamed domestic and foreign turmoil in the late 1960s and early ‘70s for diverting public attention from space travel.

With updated technology and more resources now focused on space exploration, Corney is optimistic for the future of space travel, but said it will likely never again generate the worldwide awe that the Apollo 11 mission inspired.

When he returned to the U.S., Corney went back to school to get a Ph.D. in business from Arizona State University before landing a job at UNLV. He taught quantitative classes in the business school for 33 years before retiring in 2010.

Corney said many of the people he worked with on the Apollo 11 mission have died, and their unique expertise in space voyage has gone with them. That loss, he said, is impossible to quantify.

“You don’t realize how many years have gone by, and they’ve never been able to do it since — or never spent the money,” Corney said of the lunar mission.

But Corney is hopeful that NASA will return to the moon, and maybe carry out some of the Apollo program’s plans — including an extended stay — that never came to fruition.

“It looks like they’ve got the rockets to do it,” Corney said, “if they can just figure out exactly how to do it.”

Contact Amanda Bradford at abradford@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0279. Follow @amandabrad_uc on Twitter.