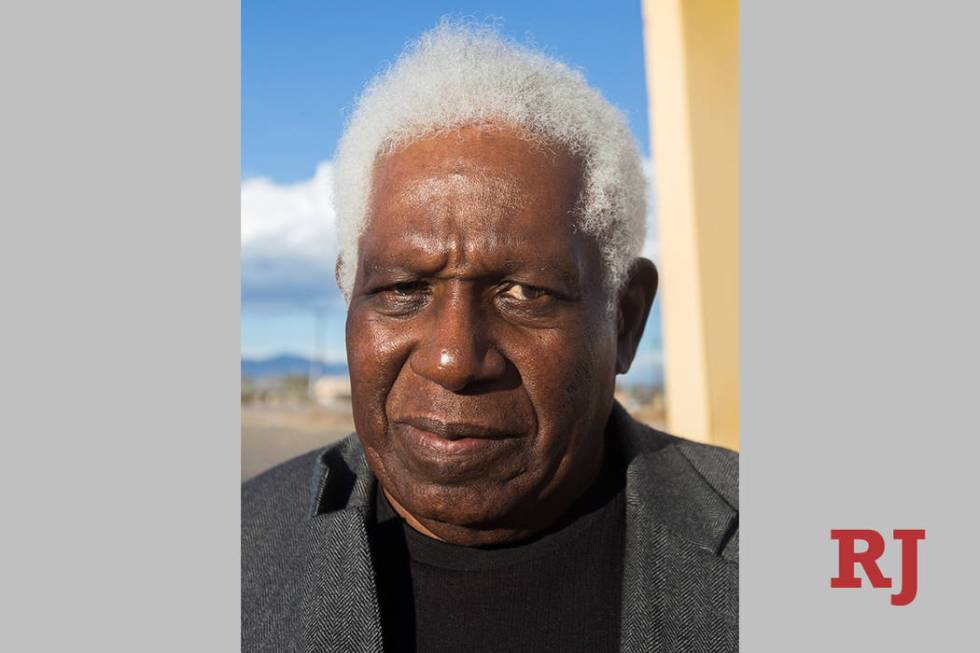

Former Moulin Rouge craps dealer QB Bush remembered as ‘pioneer’

For 30 years, Q.B. Bush made the trek during the second week of November to Northern California and returned home to Las Vegas with a load of sweet potatoes to sell.

“He was affectionately known as the ‘sweet potato man,’” said his daughter, Valora Bush, who joined him on drives in recent years. “Sometimes it was just the two of us.”

It was a 24-hour turnaround trip to Livingston, east of San Jose, but as long as Valora Bush, 60, was pleasantly distracted, she said, she never felt it necessary to relinquish her turn at the wheel.

“I used to tell him, ‘You put the Christmas carols on; I could drive all day.’ He’d be like, ‘You’ve driven all the way to Fresno!’” she recalled. “He’d be sitting there, shaking his head, and I’d be driving.”

Q.B. Bush, 88, watched over his family and invested in people, setting up a life for more than six decades in Las Vegas’ Historic Westside, according to his daughter. She described him as a straight shooter who underscored the importance of education to his three children and opened the home to their friends during her adolescence.

“He always said, ‘You have to teach those who don’t know. You have to lift them up,’” she said.

When Q.B. Bush died in late October, he left behind an assembly of family, friends and local leaders who respected him. Nearly 500 of them showed up to his funeral, his daughter said. But his passing also resonated with deeper significance to the historically black neighborhood and the city at large.

A first in Las Vegas gaming

Q.B. Bush was a craps dealer at the Moulin Rouge hotel and casino, which for six short months in 1955 was a swanky hot spot and, as the city’s first interracial casino, a pioneering establishment. He was also one of the first black dealers on the Las Vegas Strip.

“It’s like a piece of history is gone,” Las Vegas City Councilman Cedric Crear, whose Ward 5 district encompasses the Historic Westside, said about his death.

The Moulin Rouge is revered today as the host of the meeting that desegregated the Strip and downtown in 1960. But the long-vacant plot where it once sat on Bonanza Road near Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard also symbolizes the frustration of those who have hoped for years to see a memorial or revival.

Q.B. Bush participated in a Review-Journal story in February highlighting the Moulin Rouge through three surviving former employees including chorus-line dancers Dee Dee Jasmin and Anna Bailey.

“It was an A-1 place, no bones about it,” he said in the interview for the story. “And people were treated A-1, whoever they were. It was just a little too far ahead of its time, if you wanna know the truth. It was just a little early.”

The Moulin Rouge closed ostensibly for financial reasons, although many, including Q.B. Bush, have insisted it was shuttered due to pressures from Strip businesses upset it was siphoning customers, and because of its forward-thinking racial climate.

After the Moulin Rouge’s closure, Q.B. Bush opened a high-profile dealer school to help more blacks secure employment in the gaming industry, where he made a career with roles that spanned porter to management in places such as the El Morocco and Sands Hotel and Casino. He was a shift boss at Town Tavern, the in-demand club on bustling Jackson Street in the Historic Westside, a stretch as popular in the 1950s as present-day Fremont Street.

Harvey Munford, who represented the area in Assembly District 6 from 2004-16, recalled that he first met Q.B. Bush in the 1970s when Q.B. Bush was at the Sahara Hotel and hired Munford part time to deal cards. The two became good friends.

“We really looked up to him and honored him, and he was an iconic figure in our community, a legendary figure in our community,” Munford said. “He opened the doors. Most of the pioneers, the older people, all know him.”

Munford said the two would often talk about Las Vegas history, and Q.B. Bush would catalog the star entertainers such as Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin who rolled into the Moulin Rouge after shows on the Strip.

Q.B. Bush was a “pioneer” who had “a very compassionate heart and a lot of honor,” Munford said.

Crear never worked with Q.B. Bush, but Crear dealt cards at Palace Station.

“I could not have done what I did without guys like Q.B.,” Crear said. “For him to take that risk and to fight for equality and then, when the door is open, to have the guts to walk into the door … none of us will ever know what he went through to progress in his career.”

Gone, but not forgotten

Valora Bush remembered her father just as much for his other passions: He traveled across the U.S. with his family to root on the UNLV men’s basketball squad; he advocated for his preferred local political candidates and encouraged his children to be active in the community; and he was an avid golfer who belonged to the all-black Valley View Golf Club when membership in other clubs was exclusive to white people.

Q.B. Bush was also a member of The Fordyce Club of Las Vegas, consisting of blacks who migrated in the 1950s from Fordyce, Arkansas, in search of better opportunities. Elouise Bush, his wife of 50 years who preceded him in death, was also from Fordyce.

They made a longtime home on D Street, one of few areas where black people could live when Q.B. Bush arrived in Las Vegas. Munford said he could have moved anytime, except that “his heart and soul was in the community.” He sought to teach children in the neighborhood that there was more to the world than their ZIP code, according to Valora Bush, implying that it was all right to travel.

Q.B. Bush didn’t make it to Northern California to collect sweet potatoes this year, but Valora Bush vowed that the annual tradition will not be forever abandoned.

“Next year,” she said, “I will continue what he did.”

Contact Shea Johnson at sjohnson@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0272. Follow @Shea_LVRJ on Twitter.