Get a ‘dud, or it’s going to kill you’: Fentanyl deaths down, but stories tragic

Two people lay unconscious on the floor of the dilapidated apartment. Only one could breathe, although just faintly.

“What drugs; what drugs did they take,” a Metropolitan Police Department officer shouts on video caught on body cameras during the Aug. 27 incident.

“I think it’s fentanyl,” someone responds.

Metro had rushed that afternoon to encounter three people on the “brink” of becoming the latest victims to succumb to fentanyl, the synthetic opioid increasingly killing an alarming number of Americans. All three were saved, police said.

The officers, who administered the live-saving-antidote Narcan, were told that the trio had consumed cocaine later determined to be laced with fentanyl, which is said to be many times more potent than morphine.

When it promoted the dramatic footage a month later, the department highlighted a staggering statistic: the Overdose Response Team — a multi-agency task force created at the height of a fentanyl crisis in 2021 — had just responded to six suspected fatal overdoses in the previous 36 hours. Police said the synthetic drug was the suspected culprit in at least four of them.

Though distressing, the number wasn’t unprecedented, Metro Capt. Branden Clarkson noted. A year prior, the Southern Nevada Health District, for example, reported five fatalities within a 24-hour span.

But the shock value of the September overdose video was intentional, said a police spokesman.

Prolific messaging on television, the internet and billboards across the valley might be putting a dent in the death toll in Clark County, at least through mid-September, when the 144 Clark County fentanyl-related deaths represented a 19 percent decrease from the same time period in 2021, according to police statistics.

Thus far this year, there have been 513 total drug overdose deaths in Clark County from all narcotics combined, a 20 percent drop.

Meanwhile, fentanyl seized by authorities valleywide had spiked 120 percent, said Clarkson. It represents about 83 pounds of the powdery substance, or about 50,000 counterfeit pills.

Last year saw a record-shattering 801 reported total overdose deaths in the county, the highest number since at least 2015, when fentanyl was only linked to 16 fatalities.

‘Cheap, widely available, highly addictive’

Unlike previous drug crises — crack cocaine and later prescription opioid epidemics — fentanyl is said to be killing unsuspecting victims. Mexican cartels cut the substance into counterfeit prescription pills they pass off as blue M30 oxycodone pills, authorities say.

A bad batch can include pressed pills with little fentanyl, while others have fatal amounts. Just 2 milligrams of the opioid can be fatal.

Increasingly, according to authorities, the synthetic opioid is making its way into a plethora of other drugs, such as methamphetamine and cocaine, like the one consumed by the victims in the Metro video.

Consumers can either get a “dud, or it’s going to kill you,” said Clarkson, saying it “scares me.”

“It’s cheap, widely available and it has a very addictive nature to it,” said Kevin Adams, assistant special agent in charge of the Drug Enforcement Administration in Nevada. “So, I think they’ve calculated that it’s just the crux of doing business, losing some customers while many other customers are being hooked,” he said about dealers.

The Overdose Response Team comprises local police, the DEA, the Clark County coroner’s office and the Health District. It looks for trends and is increasingly pursuing murder charges for dealers alleged to have caused someone’s death.

Deterrence and education are crucial to solve the crisis, Adams said. “That’s the only way we’re going to be successful in the current battle.”

“I think it’s been very difficult to watch a day of television and not hear some type of fentanyl warning,” he said. “It’s very difficult to drive around and not see a billboard someplace that speaks about the dangers of counterfeit pills laced with fentanyl.”

Long history

Fentanyl, first invented in 1959, found a legal market to ease severe pain for some medical patients, according to the DEA.

Around a decade ago, it made its way into the black market. Mexican drug enterprises, specifically the Sinaloa Cartel and the Jalisco New Generation Cartel, import the chemicals from China and press it into pills in clandestine labs, and are then trafficked across the U.S. border.

The shipments spotted in Nevada originate from neighboring California and Arizona, Adams said. The state is a “significant location in the country” for consumption and transportation. Arrests include suspects loosely associated with the cartels, and include other independent dealers who peddle the pills on social media, he said.

“Your teenage kid can be sitting in a dinner table in front of you on a social media app, and conducting a drug transaction,” said Adams.

Total drug overdose deaths topped 100,000 in the U.S. for the first time in 2021, according to provisional figures from the Centers for Disease Control, and the 107,622 reported fatalities, mostly from opioids such as fentanyl, represented a 15 percent hike from the previous year.

Statistics show that the epidemic mostly hasn’t discriminated based on race, gender, age and socioeconomic conditions. However in Nevada, the 120 percent increase of total fatal overdoses among Latinos from 2019 to 2020 was mostly blamed on fentanyl and largely on the young male demographic, according to an analysis by the CDC and the University of Reno.

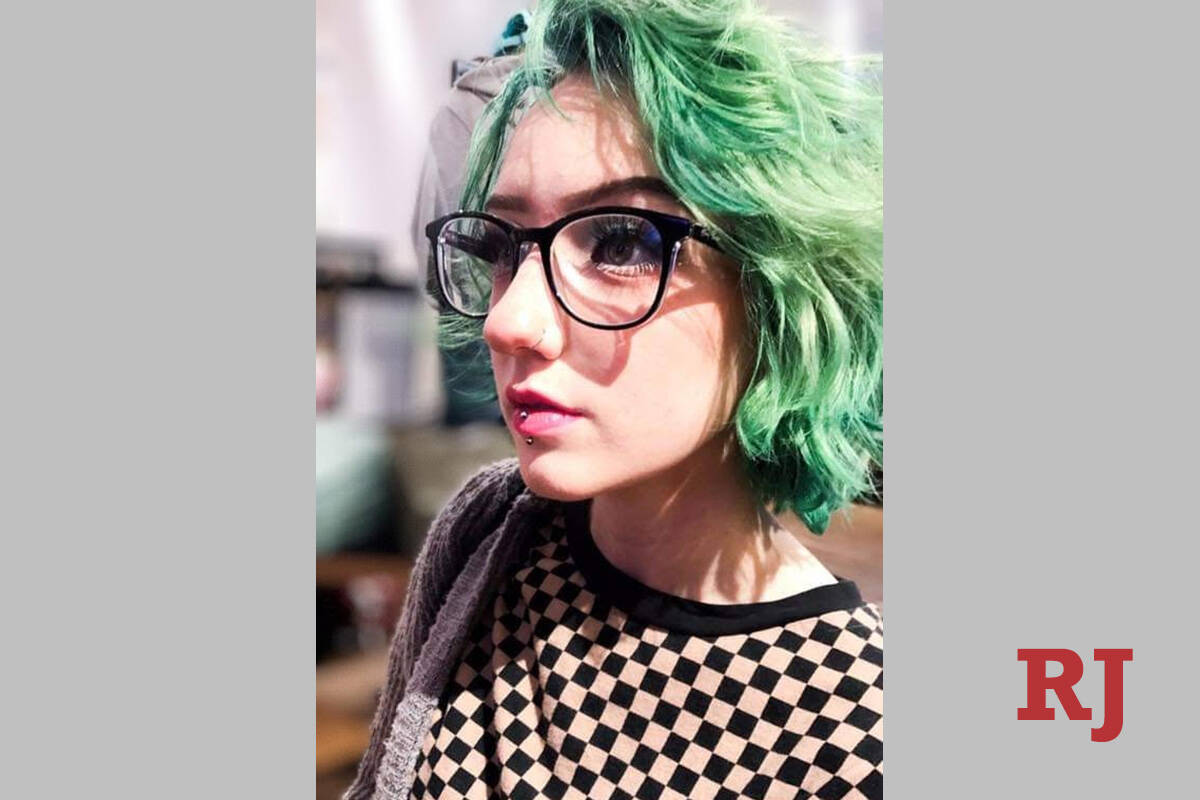

Abby White, 22

In a selfie, the young Las Vegas mother stares off to the side. The frame is accentuated by her light green hair.

Abby White’s portrait was one of the first to be displayed in a memorial at DEA headquarters in Virginia.

The section of the museum has “picture after picture after picture, wall after wall after wall, of beautiful kids, beautiful people” who’ve died from an overdose, her mother, Tiffany White, told the Review-Journal.

Abby, a cosmetologist known by her nickname, “Pinks,” overdosed on fentanyl in 2018. Fighting for her life, in a coma, she woke up after her mother whispered: “how much I love you, please don’t go,” Tiffany White said.

White said the experience left her daughter with physical ailments, but Abby dedicated herself to straightening her life, and later gave birth to a baby boy.

Then the pandemic’s isolation hit. The therapy sessions moved online and weren’t the same.

After dinner at her mother’s house on May 12, 2020, Abby went upstairs to sleep. She appeared exhausted, her mother said.

Tiffany White later found out that her daughter had taken what she thought was a Xanax as a replacement for a sleeping aid she’d run out of because of pandemic-related delays. Abby was dead a few minutes later.

“It was that quick,” the mother said. “I just hope she didn’t suffer, but they tell me they just go to sleep.”

Tiffany White has since been dedicated to raising awareness about fentanyl, and to eliminating the stigma of addiction.

She will always remember Pinks’ multicolored hairdos, her artistic talents and how “super smart and very loved” she was.

Abby White lost a friend to an overdose before her death. Within a year, four others suffered the same fate, Tiffany White said.

Hearing of the six recent deaths in 36 hours upset the grieving mother. She said she feels “complete sadness for those families” but is also angry.

“While I’m getting upset, it gets me fired up,” she added. “I need to do more. I’ve got to do more, we have to have more education; we’ve got to have better help out there.”

Contact Ricardo Torres-Cortez at rtorres@reviewjournal.com. Follow @rickytwrites on Twitter.