Pioneers of Pride: How the UNLV Gay Academic Union changed Vegas

Wigs, socks, flags, pick-up trucks: everything looks as if it had been sired by a rainbow.

It’s Friday, Oct. 7, 2022, and revelers in inflatable pink unicorn costumes roam downtown Las Vegas amid lots of confetti, topless clowns on bicycles and balloon-adorned floats with pastel signage declaring “We Are One.”

A Skittles-colored crowd lines the streets alongside them, some of them wielding circular placards that declare “Unite here!”

Thousands have been doing just that annually at the Las Vegas Pride Night Parade, the wildly spirited event in question, which returns this weekend.

It’s become the city’s signature celebration of its LGBTQ+ community, a non-stop party, full-throated rallying cry and big communal bear hug all at once.

But as outsized as the event has become, its roots are decidedly more modest, extending all the way back to a small room on the University of Nevada, Las Vegas campus 40 years ago.

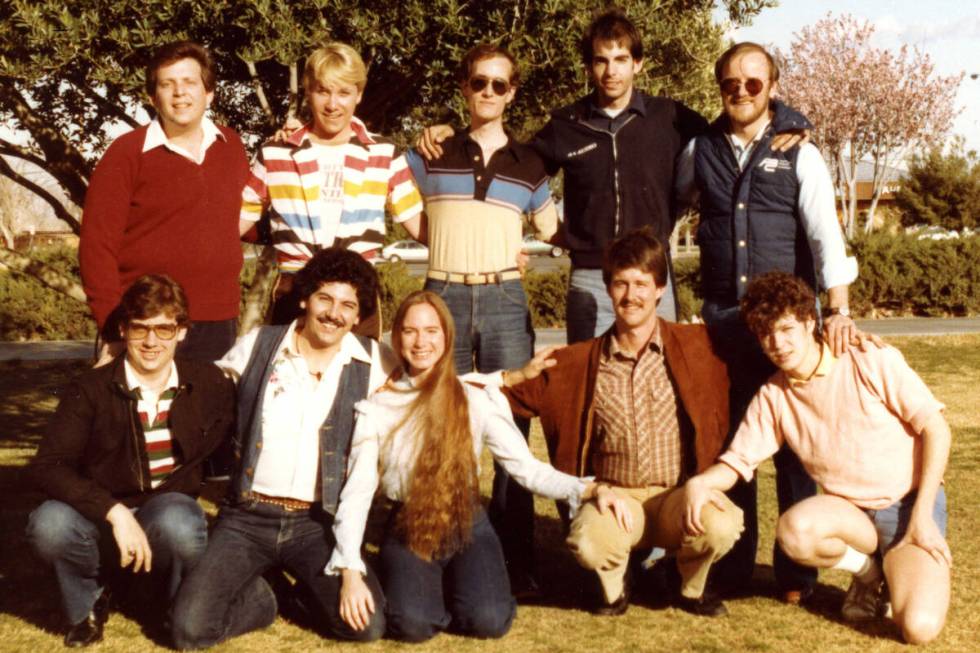

That’s where the UNLV Gay Academic Union got its start, gaining official recognition from the school in February 1983.

Three months later, they’d put on the city’s first gay pride event, in conjunction with the Metropolitan Community Church and Nevadans for Human Rights. They called it the Human Rights Seminar.

“We didn’t want to use the word ‘gay’ and scare everybody,” recalls Dennis McBride, a UNLV grad and member of the GAU from the get-go. “You would think that on the campus of the university, they would be very open and accepting, but being gay really was not. So the GAU was founded specifically to make an open presence on the university campus. It took everyone by surprise. They didn’t expect that gay people were going to be open about their orientation, expect to be recognized.”

This recognition was key.

“I think having pride, especially in those earlier years, was so important, because it was representation,” says Anthony DeFelice, an Aid for AIDS Nevada (AFAN) board member. “A lot of that wasn’t at the forefront of the community or in society or even politically. A lot of those early pride events started as protests or moments of activism. It was a way to get eyes on the problems that our community was facing at those times.”

Attracting those eyes, though, was not without its perils back then.

“There had to be some of us willing to be open and risk whatever we had to risk, because if you weren’t open, if they didn’t know you were there, how’s the community going to even be established? How is it going to grow?” asks McBride, author of “Out of the Neon Closet: Queer Community in the Silver State.”

“Gay pride was first suggested out of the GAU,” he continues, “we brought the others along with us and that went a long way toward establishing real communities and being visible. We were the engine for it.”

Out of the closet, into the neon

Down a hallway, underneath some stairs, their push to visibility began amid largely invisible confines.

It was a small space tucked into the southwestern corner of the old Moyer Student Union called the Oasis Room that served as the first official home of the Gay Academic Union, which was founded by late Liberace impersonator Will Collins in the fall of 1982, before gaining recognition from the Consolidated Students of UNLV the following year.

“If you didn’t know about it, you wouldn’t even know it was there,” McBride says of the GAU’s on-campus home. “Being put away like that, on the one hand you think, ‘Well, they want to keep us out of sight, but actually, it kept us safe from them — and it kept them safe from us, if you want to put it that way. We were allowed to be on campus and do what we were going to do.”

Collins was an Arizona transplant, where there was a thriving gay scene. The opposite could be said of his new home base.

“When he moved to Las Vegas, he saw there was no gay community, so he decided to start it,” recalls Christie Young, an early member of the GAU, who joined the fledgling organization after meeting Collins during a choir rehearsal at Metropolitan Community Church.

Though she wasn’t gay herself, Young became one of the public faces of the organization, doing local press with Collins.

“We didn’t know what would happen when we would do the publicity, we just kind of did it,” she says. “The gay community was not visible.”

Back then, said community was really a community in name only, due in large part to concerns about being openly gay in public.

In those days, Nevada’s anti-sodomy law was still on the books — sodomy would eventually be decriminalized in 1993 — with a penalty of up to six years imprisonment.

As a result, McBride says that what gay gathering spots there were back then could be targeted, stoking fears.

“Las Vegas Metropolitan Police frequently raided the bars, which was really the only place that the gay, so-called ‘community’ had to congregate and to just be together,” he recalls, “We were sort of tentatively putting a foot out of the closet, getting slapped, getting arrested, getting harassed, getting beaten.”

They faced some push-back at UNLV as well: McBride recalls one CSUN senator objecting to the GAU being formally acknowledged by the university.

“I remember him saying that we were sick and that we needed to seek medical help to cure our homosexuality, rather than having it recognized by the campus,” he says. “That was a loud voice, in a significant position.”

Still, the GAU pressed on, holding its first gay pride seminars in the spring of 1983 at the Moyer Student Union’s Fireside Lounge.

It was such a success that the GAU’s second pride event moved outdoors to Sunset Park the following year.

And then AIDS hit.

“The AIDS pandemic brought a backlash against the development of our community,” McBride says. “Of course, that snowballed, so that we were pretty much shoved back into the closet. And the gay pride events from ‘85, -‘6-‘7-‘8-‘9 were small, if they happened at all.”

But by the beginning of the next decade, things started to change for the better.

“By 1990, we kind of gotten a handle on the AIDS pandemic,” McBride says. “We started politicking again. We decided that we could not let pride die out, because that was our instrument, that was our presence in the community. And that was so important.”

Then, in 1997, Las Vegas would get its first gay pride parade.

It wasn’t without controversy.

‘We were breaking new ground with everything we did’

The city’s first pride parade wasn’t much of a parade.

“It was really just a bunch of us in our cars,” McBride says. “I was there in my little red Mitsubishi, following along with one single truck that had some people on the back of it and a couple of the bars had a car in the parade with their name on the side.”

The group trekked from a now-shuttered bar on West Charleston Boulevard to Sunset Park where the Pride Festival was being held.

But while the parade was small by today’s standards, it had big ramifications.

“It was meaningful to me, because here we were driving out on the open road, advertising ourselves as gay, going to Gay Pride,” McBride says. “Some people would honk their horns in support, other people would just look kind of strangely at us, because it was just a very, very small handful of us, all by ourselves, instead of the blocks-long parades that they have now. There was a sense of excitement. It was a bit subversive, because we didn’t have anyone’s permission to do it.”

The parade was organized by Rob Schlegel, founder and editor-in-chief of the Las Vegas Bugle, a now-defunct newspaper that focused on the LGBTQ+ community.

Because he did it on his own, without the blessing of the Vegas Gay Pride Committee, it raised the hackles of some.

“Gay Pride didn’t sanction it, and so that led to a great deal of anger and animosity among a number of people in the community,” McBride says.

“Partly, it was a matter of liabilities,” he continues, explaining why the parade was so controversial. “We didn’t use the Gay Pride Committee as a sponsor, but people assumed that it was associated with them, and so if there were matters of liability, the Pride Committee would be in trouble.”

Still, the parade served its purpose, spurring the Pride Committee to launch its own parade the following year, which has grown into a centerpiece of the Vegas Pride weekend festivities.

Its off-the-cuff origins encapsulate an era where pretty everything was unprecedented.

“When you’re a pioneer, you have no idea where the trail is going, because there is no trail,” Young says. “We were breaking new ground with everything we did. Everybody was pioneering at that time.”

Different name, same aim

Times have changed and so has its name, but the Gay Academic Union’s legacy lives on even if the organization no longer does.

Since its founding, the GAU has morphed into a series of similarly-minded groups on campus, among them: the Lesbian and Gay Academic Union; the Lesbian, Gay, Bi-Loving Association, the Gay Straight Freedom Alliance and others.

Spectrum is UNLV’s current LGBTQ+ student organization.

For Ash Quinn, who oversees Spectrum as well as QUNLV for university faculty members, the organization serves much the same purpose that GAU did for his predecessors four decades ago.

“When I was younger, I grew up in a household where I couldn’t explore my identity,” he says. “And Spectrum was the first group that I ever joined.

“I think one of the biggest things — especially right now, in the current political atmosphere — is finding spaces that you can be in community with others,” he continues, “just for that social aspect, as well as finding that sense of support and shared advocacy.”

Though a celebratory, familial atmosphere powers Vegas’ pride week festivities, it’s this advocacy that Quinn speaks of that remains at the core of the event, according to John Waldron, CEO of LGBGT+ community center The Center,

“Pride celebrations really were not celebrations in the early days, they were protests,” Waldron says. “They were our communities standing up and saying that we were going to have a voice and we were going to finally demand equality. Over time, they became a celebration of all of our achievements along the way.

“We want to continue to celebrate and be proud of who we are,” he adds, “but also, we see some trends across the country that remind us that we have a lot of work still to be done and that a lot of our folks are not treated fairly and not treated equally. We need to have those events and those activities so that we get our voice out there.”

Where did that voice first emanate in Las Vegas?

From the Gay Academic Union.

“There were so many gay people later on who held positions of authority — political authority, financial authority and social authority in Las Vegas — who were out,” McBride says. “We were the first ones who were out and we set the tone, laid the foundation for everything that came later.

“Now, we are so integrated in the community here, that it’s almost as though we’re not a gay community,” he notes. “It’s a community with a lot of gay people in it.”

Contact Jason Bracelin at jbracelin@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0476. Follow @jbracelin76 on Instagram