70 years ago, nuclear testing ushered in a new era for Nevada

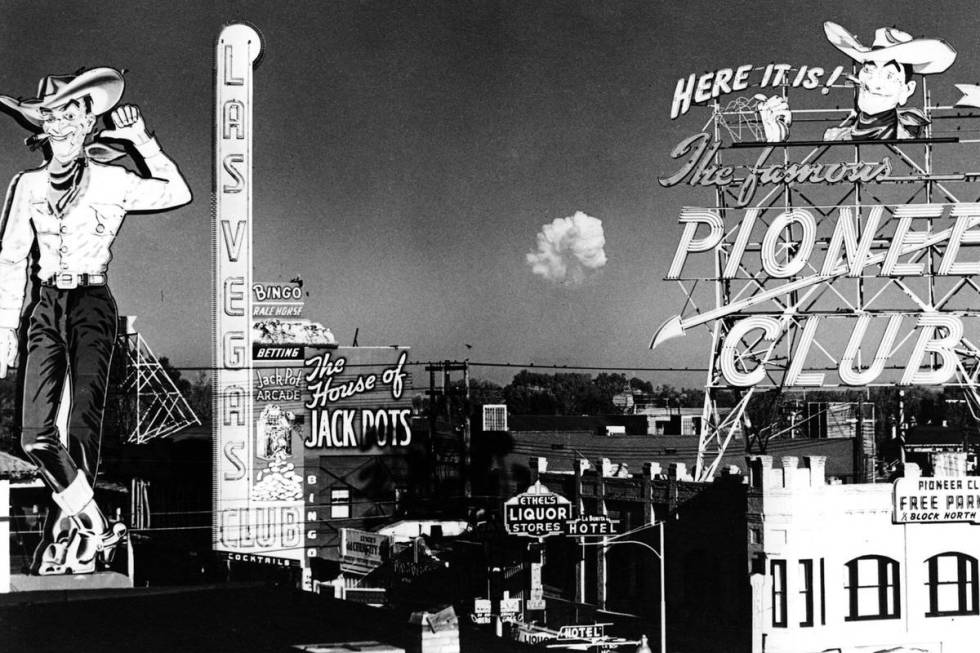

Seventy years ago, an atomic blast detonated in a remote, sprawling swath of desert known as Frenchman Flat was seen and felt in Las Vegas, 65 miles to the southeast.

The Review-Journal’s coverage the next day, on Jan. 28, 1951, featured reports from the public, some of whom were awakened by the shockwave or who witnessed a blinding, white flash, or had described a “borealis effect” spread over the whole sky to the northwest.

“VEGANS ‘ATOM-IZED,’ ” the newspaper’s headline read in big, bold and all-capitalized letters splashed across the front page.

There were more than 1,000 atomic tests in Nevada’s desert between 1951 and 1992, including about 100 above the ground, but this one was the first in that succession. It was also the first such test in the U.S. since an experimental atomic explosion in New Mexico six years earlier.

The blast ushered in a new era of Nevada history that previously had been relegated to the perceived uncouth behavior of gambling, prostitution and easy divorces.

“It legitimized Nevada; we were just kind of an outlaw state,” said Rep. Dina Titus, D-Nev., who in 1986 published a book, “Bombs in the Backyard,” that looks at the Nevada Test Site through a political and cultural lens.

“I think it will always be seen as contributing to us winning the Cold War and rightfully so,” she said.

Shifting attitudes

Beyond providing a significant economic stimulus, atomic testing in the state was viewed by many as patriotic during a tense Cold War era, and it fit easily into popular culture: There were hairdos, movies and the Miss Atomic Bomb pageants. And that view of Nevada’s relationship with nuclear weapons has largely persisted over time to become part of nostalgia, Titus said.

But political attitudes about nuclear testing have shifted over the decades, as has the tendency of the general public to trust its government about safety, according to Titus and local historians. Titus has led the opposition to storing nuclear waste at Yucca Mountain and last year introduced a bill to prevent then-President Donald Trump from restarting explosive nuclear weapons testing.

Meanwhile, the cultural reverence of Nevada’s atomic past slips with each new generation.

“Time is passing us by, and that’s why we need to keep the history and the importance of testing in Nevada, at least among the young people,” said Chuck Costa, vice president of the Nevada Test Site Historical Foundation, which operates the National Atomic Testing Museum. “To me, that’s key.”

Unsung heroes

At the time, testing was a relatively easy sell: America had to protect itself from foreign aggression, and its “good bombs” had to be better than those possessed by the Russians, who were testing nuclear weapons themselves, according to UNLV history professor Michael Green.

Add in the McCarthy-era suspicions that communists were hiding in America, and “even if you were inclined to question this, many would be leery of that,” he said.

Even workers at the test site who years later were struck by illnesses, such as cancer, maintained a sense of pride over their contributions to the country’s defense, according to Amy Austin, the regional outreach director for Nuclear Care Partners, which provides in-home care and lobbies for former atomic workers who have fallen ill.

“I’ve never once met a former worker who said they regretted it and wouldn’t make the decision to go work and serve their country in that fashion if they had to do it all over,” she said about her nearly seven years with the nationally accredited group.

Austin said that the workers are unsung heroes who do not receive the recognition they deserve. Ruben Mendoza, a regional business development specialist for Nuclear Care Partners, which operates in at least 16 states — Nevada is its largest branch — said he has helped thousands of former workers over the past seven years.

There were between 8,000 and 15,000 workers on any given day at the Nevada Test Site, a massive area bigger than Rhode Island, according to Mendoza. He said now there is a concentration of cancers in Nevada and surrounding cities.

“It’s definitely taken its toll,” he said.

An American West story

The site is now known as the Nevada National Security Site and still conducts underground subcritical experiments — meaning “no self-sustaining nuclear fission chain reaction will occur” — to gather data about nuclear weapons, according to its website.

Titus said the onus is now on officials to find a broader use for the land, such as cybersecurity or hazardous cleanups, to become an economic engine as opposed to simply a relic.

As for its legacy, UNLV History Department Chairman Andy Kirk said nuclear testing in Nevada was “the biggest science experiment in human history.” It would be the defining story of almost anywhere else, but it fades to the background in a city like Las Vegas so well-known for its cultural aspects.

Kirk, who has conducted extensive oral history about the test site and authored the graphic novel “Doom Towns,” viewed testing as fitting well into the larger narrative in the American West, not unlike subsidized railways and Hoover Dam: A vast region is used by the U.S. government for major projects to both the great benefit and sometimes harm of its residents.

But he also noted how he too often finds that students do not know much about it.

“The story is way too important to have it fade,” he said. “There’s just no way to understand modern Las Vegas without knowing the story of nuclear testing.”

Contact Shea Johnson at sjohnson@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0272. Follow @Shea_LVRJ on Twitter.