El Niño is coming, but will it be a super one?

An El Niño winter is ahead, weather forecasters firmly believe. The question they are pondering is exactly how strong it might be.

Locally, the worldwide weather factor is mostly known for directing heavy moisture toward California and the Southwest as temperatures warm several degrees across the eastern and central Pacific Ocean.

Current forecasts for much of the West and Southern Nevada call for a possibly warmer winter with about equal chances for below or above normal precipitation.

The pattern’s arrival was declared in June, by which point there were already signs of unusual warming in the Pacific and other waters around the world, according to the Climate Prediction Center of the National Weather Service.

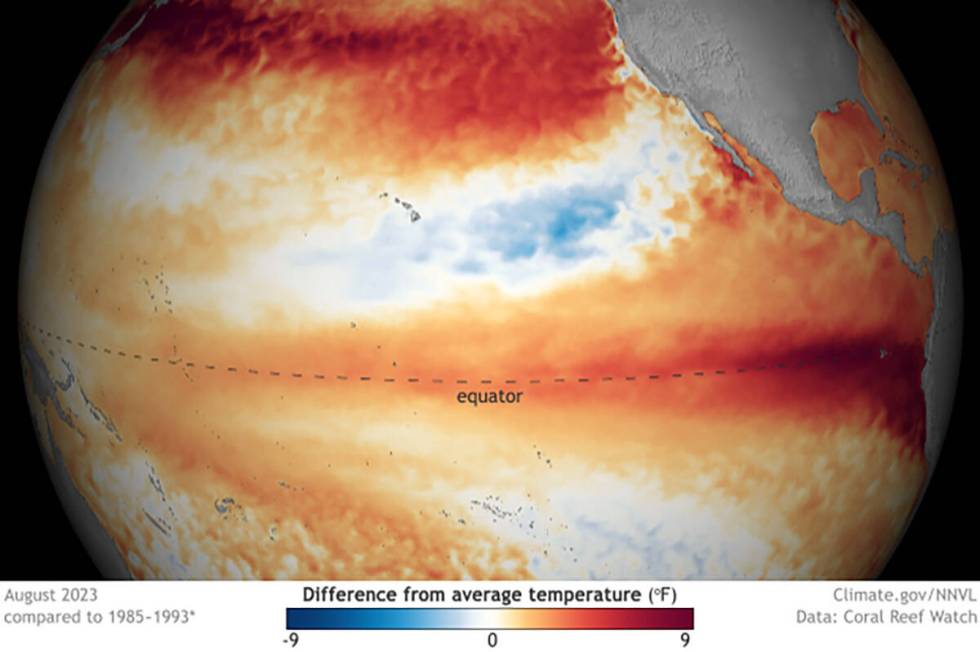

The phenomenon is marked by a surge of warmth in surface waters along the equator. The warmer those waters become, and the more they couple with west-to-east flowing winds over the Pacific, the stronger the El Niño and its influence on global weather.

El Niño and La Niña are opposite phases of a natural pattern across the tropical Pacific that swings back and forth every 3 to 7 years on average. El Niño and La Niña alternately warm and cool large areas of the tropical Pacific, which influences where and how much it rains.

Triggers rainfall, wind changes

The arrival of El Niño triggers several changes in tropical rainfall and wind patterns around the globe. By modifying the jet streams, El Niño and La Niña can affect temperature and precipitation across the U.S. and other parts of the world. The influence on the U.S. is strongest from December to February, but it may linger into early spring.

In the U.S., the most significant impact is a shift in the path of the mid-latitude, high-level jet streams — winds that play a major role in separating warm and cool air masses and the steering of Pacific storms across the U.S.

Early this summer, El Niño was forecast to stick around at least through January-March 2024, and now there is about a 71 percent chance that the event peaks as a strong El Niño, long-range weather forecasters reported this week.

Climate models have suggested the potential for an intense El Niño that could trigger floods, heat waves and droughts.

A textbook El Niño includes tendencies toward dry conditions in places such as Indonesia, northern Australia and southern Africa and wet conditions across parts of South America, eastern Africa and the southern tier of the United States. Signs are already suggesting a hot and dry summer in store for Australia, for example, where authorities are warning of heightened wildfire dangers.

There are signs that rising temperatures could increase El Niño’s capacity to trigger heavy rainfall in some parts of the globe, though, said Yuko Okumura, a research scientist at the University of Texas.

“It’s likely the impact might be stronger,” Okumura said.

A forecast that the National Center for Atmospheric Research issued Tuesday was even more bullish, using a new prediction system to forecast that this winter could bring a super El Niño rivaling the historic one of 1997-1998. That winter brought extreme rainfall to California and Kenya, along with intense drought to Indonesia.

“We might be facing a similar winter coming up,” said Stephen Yeager, a project scientist at the center who helped lead the forecasting. “This is one plausible future.”

One model predicts muted El Niño

However, one model predicts the El Niño will be a little less intense than the last super El Niño in 2015-2016, which was tied to severe coral bleaching in the Great Barrier Reef, record cyclones in the Pacific, drought and fires in Australia, a historic snowstorm along the U.S. Mid-Atlantic coast and disease outbreaks around the world.

Making it harder for forecasters is that the same conditions don’t always develop with each El Niño. Every event is somewhat different. The influence of El Niño on U.S. winter climate is a matter of probability, not certainty.

Though El Niño is known for bringing moisture flowing to California and the Southwest, for example, that pattern is not yet emerging, largely because strong wind patterns are not emerging, forecasters noted. When last winter delivered record precipitation to those areas, it came on the tail end of a lengthy stretch of La Niña conditions — known for a tendency toward drought there.

“The forecasts right now are showing a fairly muted response” to El Niño in the United States, said David DeWitt, director of the weather service’s Climate Prediction Center.

As for Southern Nevada and most of the West, NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center is projecting an equal chance for precipitation to be below or above normal this winter. For temperatures, the Climate Prediction Center gives the region a 33 to 40 percent chance of being above average.

Contact Marvin Clemons at mclemons@reviewjournal.com.