After 80 years, missing Reno banker still mystery

RENO — “Roy J. Frisch stepped into oblivion yesterday.” — Nevada State Journal, March 23, 1934

An unnamed reporter of the Nevada State Journal would never know how prophetic his words were that day. Eighty years later, the whereabouts of Roy Frisch, a former Reno city councilman and the head cashier of the Riverside Bank, remain unknown.

It is one of the city’s most infamous unsolved mysteries — a much older and Nevada-centric version of Jimmy Hoffa, if you will.

For decades, Roy Frisch’s family left a porch light on at their Court Street home, waiting for his return. On Saturday, it will be 80 years since Frisch told his mother and sisters that he was going to see a movie and vanished.

“It’s one of Nevada’s great mysteries, and certainly one of Reno’s great mysteries,” said Phillip Earl, curator emeritus at the Nevada Historical Society, who has written extensively of the Frisch case. “I always think when they find a body out in Nevada that they found Roy Frisch.”

As recently as 1996, the Reno Police Department reopened the case to investigate a lead. But the mystery lives on.

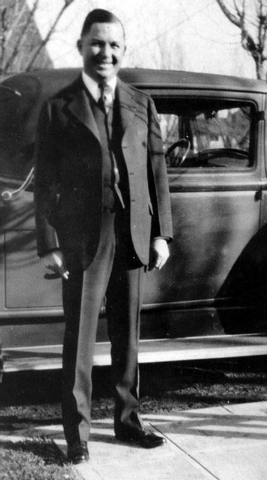

Roy Frisch grew up in Reno and was a veteran of World War I. He served as a Reno city councilman and as the Washoe County assessor before taking a job as the head cashier at George Wingfield’s Riverside Bank, the job he held at the time of his disappearance.

The Nevada State Journal described Frisch as a model citizen who didn’t drink alcohol, smoke or gamble. At the time of his disappearance, he was 45 years old and lived in the family home at 247 Court St. with his mother and sisters, Alice and Louisa.

On March 23, 1934 — the day after his disappearance — Frisch was scheduled to testify to a grand jury that was investigating a confidence scheme involving Reno “sportsmen” William J. Graham and James C. McKay.

Graham and McKay are described by retired Nevada State Archivist Guy Rocha as “the overlords of the underworld in Reno.” In 1933, they were indicted in a mail-fraud scheme that bilked investors out of thousands of dollars. The transactions took place at the Riverside Bank, and Frisch was to be the government’s key witness in their trial. His testimony already had resulted in the conviction of several New York residents involved in the scheme.

At the time, Reno was also a hotbed of activity for some of the country’s most notorious gangsters, including bank robber Lester Gillis, better known as “Baby Face” Nelson. Nelson was a known associate of Graham and McKay, having been involved in their bootlegging operation during prohibition.

Nelson and his criminal associate, John Paul Chase, were in Reno on the night that Roy Frisch disappeared, and many, including Frisch’s assistant cashier Joseph Fuetsch, were convinced that Nelson had abducted and killed Roy Frisch.

Fuetsch’s daughter, Joel Fuetsch Pehanick, said her father was convinced from day one that Frisch had been killed. Joseph Fuetsch became the government’s key witness after Frisch disappeared and was under protection of federal agents. (After two mistrials, Graham and McKay were convicted in 1938 and sent to federal prison.)

Pehanick wrote the novel, “Porch Light Burning,” which detailed the trials.

In 1935, John Paul Chase (arrested and facing a long prison sentence) told FBI agents that Nelson had killed Frisch and they dumped his body in a mine shaft east of Reno, but he later recanted that testimony.

In the days after Frisch disappeared, a reward of $2,000 was offered for information on his whereabouts. There was some speculation he had been bribed to skip town. Another theory was that he had suffered a bout of amnesia and couldn’t find his way home. Numerous abandoned mine shafts were searched to no avail. A human leg found near Tonopah sparked speculation, but was determined not to belong to Frisch.

Earl said there was speculation that he had been taken to Lake Tahoe, weighted down and dumped in the lake. Frisch was declared legally dead in 1943, which allowed his mother to collect insurance and benefits owed to her son.

In 1996, the Reno Police Department reopened the case. There was speculation, long rumored, that Frisch had been killed but wasn’t taken out of town at all. Instead, he’d been buried in the backyard of George Wingfield, whose house happened to be next door to the Frisch family.

Earl said he was approached by parties who would be willing to use ground-penetrating radar on the Wingfield lot, but the property owner declined to allow them to use it.

He hopes one day, the property will sell and whoever buys it will either dig a new foundation for a building or allow investigators to conduct their search with the ground penetrating radar.

“Until then, we just don’t know,” Earl said. “It’s a mystery.”

At least for now, Roy Frisch remains in oblivion.