West Virginia shows Nevada, other states, the way on COVID vaccines

CHARLESTON, W.Va — Inez Washington lost her aunt and sister to COVID-19, so she was quick to bring her aging mother, Betty Johnson, to a community center where they received their first shots of the Moderna vaccine last week.

“It’s not been really good for our family,” Washington said of the pandemic. “We’re losing them in twos. It’s really hurtful.”

Washington is one of 230,596 West Virginians who as of Friday morning had received at least one dose of a coronavirus vaccine, according to statistics maintained by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That compares with 308,611 shots administered in Nevada, which has a population almost twice that of West Virginia.

West Virginia has received 387,700 doses and has administered 91 percent of them, while Nevada has received 533,800 and distributed 74 percent, according to CDC statistics.

More telling, 120,819 people in West Virginia have received two doses of the vaccine and have been fully vaccinated; in Nevada, just 83,485 people had been fully vaccinated as of Friday morning, CDC figures show.

An aggressive statewide attack using county health, emergency medical, small pharmacies and community-based groups has made the difference in West Virginia. The state has done so well at delivering the vaccine that the CDC has consistently ranked it as highest in effective distribution and vaccination in the country.

“West Virginia is knocking it so far out of the park, it’s unbelievable,” said Republican Gov. Jim Justice during a recent news briefing.

In Nevada, by contrast, many residents remain frustrated that they cannot make appointments to get a shot or get answers from officials and experts about when the situation will improve. Nevada remains one of 12 states not yet administering doses to those ages 65-69, and it will likely be weeks before that changes. A Review-Journal analysis found that Nevada has been shortchanged in getting doses of the vaccine.

Community rallying for shots

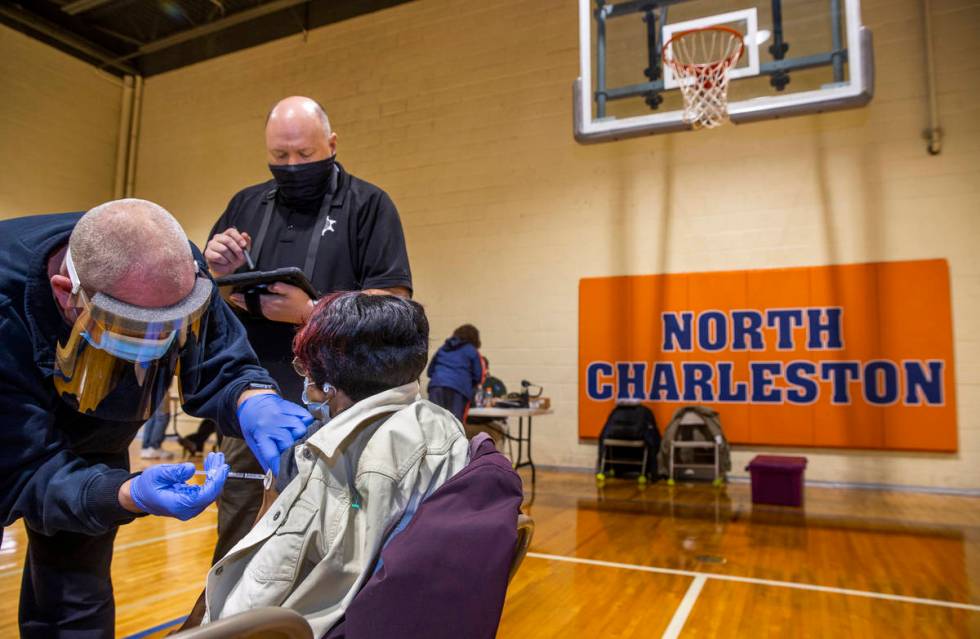

The vaccinations for Washington and Johnson were made available by the Kanawha County Health Department, under the direction of Dr. Sherri Young, and the Rev. James Patterson with the Partnership of African American Churches.

Young and Patterson worked to conduct a small vaccination program where about 440 people from the working class North Charleston neighborhoods could get the vaccine at a nondescript red brick community center.

The county program is like others empowered by the state of West Virginia to aggressively deliver the vaccines to halt the spread of the deadly disease.

The rural state has been crippled by the crumbling coal industry, the Appalachian opioid epidemic and low health care rankings. A United Health Foundation survey and report in 2013 titled “America’s Health Rankings” ranked West Virginia as last, or second to last, in 20 health categories, including cancer, diabetes, prescription drug overdoses and senior critical care.

Roughly 6 percent of the state’s residents lack public or private insurance, compared with 9 percent nationally, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. In Nevada, 11.4 percent of the population is uninsured.

Yet, as West Virginia rolled out its initial COVID-19 plan, it was able to inoculate those in nursing homes quickly. By the end of January, West Virginia had used 99.6 percent of its supply of first vaccine doses, according to the CDC.

“I want the shots in people’s arms,” Justice said. “If we’re at 99.6, I want to take it to 100 percent. We want to not only lead the whole nation, we want to lap the field.”

Comparatively, Nevada was ranked near the bottom by CDC. The Silver State distributed about 55 percent of its vaccine, though Nevada officials said it was closer to the 60 percent range where most other states landed.

Rocky rollout for most

For most states, including Nevada, the rollout of the vaccine was rocky. Many used different methods to deliver the vaccines and inoculate the first group of those eligible to receive them. And many followed a federal plan that relied heavily on large pharmacy chains and state health departments.

Nevada lawmakers and state officials said the low rankings were the result of bureaucratic delays in requesting and receiving doses, as well as being shortchanged on the number of vaccines. The state received 9,316 doses per 100,000 population, while the median allotment was 1,000 per 100,000 population.

Rep. Dina Titus, D-Nev., blamed the Trump administration for its failures in the distribution system.

“Nevadans are suffering the consequences,” she said.

Nevada, like other states, opted into the federal program that relied heavily on Walgreens and CVS for distribution of the vaccine. But West Virginia saw problems with the heavy reliance on large pharmacy chains, primarily because many of its residents live in communities served by several smaller, independent chains.

Indeed, about 54 percent of the state’s pharmacies are not chain-affiliated, said Andrea Lannom, a spokeswoman for the West Virginia Department of Health and Human Services.

For that reason, West Virginia was the only state to opt out of the federal program under the Trump administration.

Local chain takes lead

Instead, the state used smaller regional chains, such as Fruth Pharmacy, which has fewer than 20 stores in the state and had a proven record with COVID-19 testing programs, to vaccinate nursing home residents.

“If we only opted into the federal program, we felt we would be limiting our ability to distribute and administer the vaccine to the population in need,” Lannom said.

For now, the state is enjoying great success, said Lynne Fruth, president of Fruth Pharmacy, which operates a small chain of hometown pharmacies in West Virginia, Ohio and Kentucky.

Fruth, who is also on the State Pharmacy Board, teamed with Dennis Zimmerman, Mason County director of emergency services, to begin a vaccination program delivering doses to nursing homes along the Ohio River in West Virginia.

Mason County is home to the headquarters of Fruth Pharmacy, started decades ago by Fruth’s late father. She likes to point out that Fruth is competitive with national chains because they lack ties to the community.

“Even though we’re known as being a small chain, we are also known as being very scrappy,” she said.

Fruth said she worked with state officials to stake out a plan for West Virginia to receive its share of vaccines. Fruth said West Virginia officials were concerned the bulk of the vaccines would go to large population centers and smaller communities would be overlooked when it came to allotment.

She shared her concerns with the governor and state health officials.

“If we don’t fight for this vaccine right out of the gate, we are going to get the scraps,” Fruth recalled telling state officials.

Not only did the small chain prove its mettle with COVID-19 testing, initiating drive-up methods to quickly test the population in areas of the state where its stores were, it delivered on vaccinations.

As Zimmerman ordered more vaccines, he was asked how he planned to store the Pfizer vaccine that required almost immediate use after being removed from deep refrigeration.

“We’re going to store that vaccine in people’s arms,” Zimmerman said.

Drew Massey, Fruth director of pharmacy, also realized early that Pfizer vaccine vials of five doses actually contained an additional one or possibly two more shots.

Instead of discarding the vials after five doses, and after nursing home and staff were inoculated, Massey used the remainder of doses to vaccinate age-eligible residents at assisted-living centers, which were often adjacent to the nursing homes. Because of the shelf life of the Pfizer vaccine, that meant getting quick consent from patients’ adult children in the evening.

Fruth said Massey was “squeezing out every last drop.”

“Every dose went into an arm,” she said. “We have not wasted a single dose.”

Big states, small numbers

CDC statistics show that many states with larger population, including Nevada, have experienced lower vaccination rates.

Alaska, West Virginia and Connecticut have the highest percentage of their populations receiving the first dose of vaccine, while Iowa, Kansas and Idaho have the lowest with Nevada, California and Texas just slightly better, according to the CDC.

The Trump administration’s Operation Warp Speed accelerated the process to produce and distribute the vaccine, but left it up to each state to decide how to administer the doses.

Gov. Steve Sisolak, a Democrat, and Nevada’s congressional delegation are pressing the Biden administration to adjust the formula and send more vaccine to the state.

“Every day, my staff and I are on the phone with our leaders in Washington,” Sisolak said at a news conference on Thursday.

Nevada isn’t alone.

Maryland Gov. Larry Hogan, a Republican, said the “demand will far exceed the supply we have available to us.”

President Joe Biden signed an executive order to use the Defense Production Act to ramp up the supply. And a new vaccine is expected to be available soon from Johnson & Johnson to complement those from Pfizer and Moderna.

“Right now, the biggest issue West Virginia is facing is the need for more vaccinations,” said Lannom, the state health department spokeswoman. “The state continues to ask for more vaccines so we can get them in arms as quickly as possible.”

The Biden administration is deploying the National Guard and Federal Emergency Management Agency to boost distribution efforts to states like West Virginia, where county health departments and small pharmacies were urgently using vaccines immediately after delivery.

This week, the Biden administration plans to send out an additional 11 million doses to states and tribes, a 28 percent increase since the president took office Jan. 20. And the administration announced the launch on Feb. 15 of its community health centers vaccination program to reach under-served communities, much like the one in North Charleston.

Biden has set a lofty goal of 100 million doses in his first 100 days.

Help from soldiers, hospitals

Young, at the North Charleston Community Center, said the vaccines used during the program were distributed by the National Guard and allocated by a multi-agency task force.

She said the county has been able to partner with hospitals to give 3,870 doses in one day, as well as join with smaller clinics and the Partnership of African American Churches to deliver 440 vaccinations.

The smaller clinic in North Charleston was also “about building trust,” Young said.

African Americans make up about 4 percent of the population of Charleston. Young said the vaccination clinic was an outreach effort to those that may be reluctant to get vaccinated.

“I brought about 440 doses today,” Young said. “And if every one of them goes home and in someone’s arm, then that’s a good day.”

Patterson said that in the beginning of the pandemic, there was a “lot of skepticism about the vaccine.” African Americans distrusted the health care system. But an urge to get back into the community, and a fear of the virus, has prompted many to seek it out.

“There has been a huge turnaround with the number of people of color willing to take the vaccine,” Patterson said.

For Inez Washington, the decision to get the vaccine was relatively easy. After all, she has watched relatives die from the disease.

“We just buried my sister last Saturday,” she said.

Though West Virginia is doing more than other states in vaccinating people, Washington put it all in perspective: “We’re still losing a lot of people here.”

Contact Gary Martin at gmartin@reviewjournal.com. Follow @garymartindc on Twitter.