JANE ANN MORRISON: Passing of old Vegas figure spurs memories

My first political corruption trial was a lesson in crooks, kickbacks and double-dealing in Las Vegas.

I was a reporter, not a defendant.

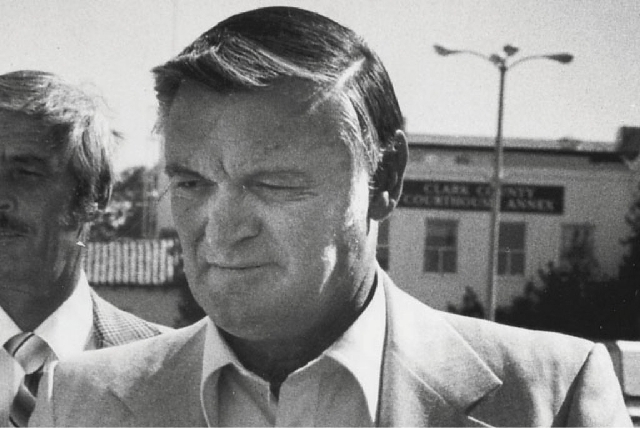

The defendant was Eathel “Tex” Gates, a handsome 52-year-old cowboy with silver hair distinguishing his temples.

The attorneys were among the city’s best, federal prosecutor Larry Leavitt and defense attorney John Fadgen.

The crime involved what seemed like a lot of money in 1979 — more than $147,000 in kickbacks.

And prosecutors suspected, but never proved, that some of that money may have ended up in Sheriff Ralph Lamb’s pockets, which Lamb denied Wednesday.

Peripheral characters included Harry Claiborne, a federal judge later imprisoned for tax evasion, and there were ties to Al Bramlet, a Culinary leader who before he was murdered, first suggested a $500 payoff to keep Gates happy.

This trial was old Vegas, where the main witnesses had immunity for their bad deeds and seemed more crooked and sleazy than Gates.

Gates was the director of the Clark County Business License Bureau, a job he held from 1967 to 1978. It was an appointed job, and the man with the power to appoint was Lamb because the license bureau was under the sheriff’s jurisdiction then. Gates held enormous power deciding who received a business license and who did not.

When I saw his obituary in Tuesday’s Las Vegas Review-Journal, the name “Tex Gates” jumped from the page into my memories of 34 years ago.

Gates had died in tiny Rye, Ark., on June 23 at age 86.

His 10-day trial showed the underbelly of Las Vegas, the bribes offered (and accepted) for the right to do lucrative legitimate business in this city by selling show tickets and arranging time-share presentations from booths that had to be licensed.

Gates received as little as a quarter per show ticket up to $1 for a couple willing to sit through time-share pitches. But those small amounts added up between 1975 and 1978.

Gates was convicted of 62 counts of extortion, one count of obstruction of justice and one count of perjury for lying to the grand jury. The jury would have convicted him of another 18 other counts of extortion and three counts of income tax evasion, but there was a holdout who didn’t believe one witness was telling the truth when he testified he paid $9,800 in cash to Gates.

That witness, Ray Warren, had partnered with Culinary union boss Bramlet in a company that sold show tickets.

Defense attorney Fadgen argued Warren was taking the supposed bribes to Gates and pocketing them himself as a way to steal from Bramlet. Several jurors found it reasonable that Warren, a failed Assembly candidate, would cheat the powerful union boss.

Gates took the stand and accused nine of the government’s witnesses of lying.

The main witness, David Bliss, had paid his $137,000 by check and marked the checks with Gates’ initials.

Bliss testified during the trial that he gave kickbacks to Gates “because he was a dear friend and I felt if I gave him this money I wouldn’t have problems businesswise.”

Gates testified the checks were gifts but he did nothing for those gifts. He declared the Bliss money as income on his taxes, but not the Warren-Bramlet money. Over the years, he asked Bliss to write the checks to different names, not his.

The presiding judge was Claiborne, who later had his own run-in with federal prosecutors over his tax returns, leading to his impeachment.

But when Claiborne sentenced Gates to eight years in prison, later reducing that to five years, his harshest words were for Bliss.

“Bliss is the greater culprit of the two, as far I’m concerned,” the judge said.

Claiborne attacked the businesspeople who offered bribes to public officials and said their guilt was “much greater than the public official who finally gives way and whose resistance is low.”

Gates entered prison in June 1980 and was paroled November 1982.

Naturally, none of this was in the obituary submitted by the family, nor even that Gates was the business license director for Clark County. There was no mention of his trial, or his prison time. Family members are not going to mention the parts they would rather forget.

The obituary said Gates grew up in Texas and moved to Las Vegas in the 1950s. During his early Las Vegas days, he operated a dude ranch known as Twin Lakes Stables, provided horses to the movie industry and served on the Clark County sheriff’s posse.

“He loved to cater to his friends with early morning horseback breakfast rides, which included Roy Rogers and Liberace,” the obituary said.

Among his other accomplishments, he made television commercials for cigarettes and Ford Mustangs. He was a U.S. Army veteran and served during World War II in the U.S. merchant marine in the Pacific.

After 40 years in Las Vegas, when he was released from prison, he began a new life with his wife, Susie, in Arkansas, starting the T&S Ranch and serving on boards and associations having to do with farming and cattle ranching in Cleveland County.

Before he left, he was subpoenaed to testify before a federal grand jury investigating Sheriff Lamb. Whatever he said never resulted in any indictment against the sheriff.

The sheriff, the hero in the canceled TV show “Vegas,” said he didn’t know Gates was taking kickbacks, or he would have done something about it.

“I warned him about these guys being bad guys; I thought that would shut him down. I said: ‘Tex, don’t lie to me, tell me the truth,’ ” Lamb said in his slow, easy drawl.

The Gates investigation and the effort to link Lamb to the kickbacks were reasons Lamb lost his election in 1978 after 18 years in office. That, and some other things.

Tex Gates’ saga of corruption never made it into “Vegas.”

I was to learn that public corruption trials here were not a rarity and that some officials sold themselves out cheap while others demanded big bucks and “favors.”

Jane Ann Morrison’s column appears Monday, Thursday and Saturday. Email her at Jane@reviewjournal.com or call her at 702-383-0275.