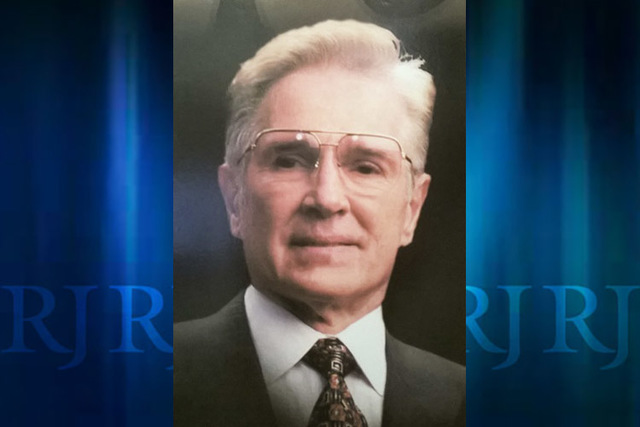

Photographic memory rare but invaluable for Robert Griffin

If you had a photographic memory, how would you use it?

Robert Griffin could have used his relatively rare skill to count cards in Nevada casinos. Instead, he used it to identify card counters and stop cheaters.

Beverly Griffin, his former wife and his partner in Griffin Investigations, told how Bob Griffin’s abilities pinpointed card counters and identified cheaters as far back as 1967, when he began his business with her, a venture she still runs.

Griffin died Oct. 9 at age 88, but his passing received scant attention. His fourth wife didn’t do an obituary. But Beverly, his third wife, reached out to me, thinking he deserved attention as a trailblazer in Las Vegas’ gaming reaching back to the Howard Hughes era.

As she spoke, I remembered some of the investigations. I had written about one cheating case in federal court — the Dennis Nikrasch case.

Griffin Investigations’ most notable investigation was helping identify a team of young and mostly Asian card counters from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology that took casinos for millions in the 1980s.

One team member would count the cards, then use signals to tell another team member what to do next. A big stretch. A tug on the ear.

“At one point, 100 people all over the U.S. were part of the team,” Beverly said.

The team was not prosecuted because card counting is not considered cheating. But Griffin remembered faces and would put their faces in the Griffin Book. He’d sell the information to casinos and give it to law enforcement for free.

Card counters insist they are skilled players, not cheaters. But casinos don’t want them around and in Nevada, they have the right to tell them to leave.

But card counters come back, often in disguise.

Griffin had the amazing ability to recognize people despite disguises. One man disguised himself with glasses and a wig when posing for a jackpot photo at the Lady Luck. Griffin recognized him from his wristwatch, Beverly remembered.

Once Griffin saw a man gambling in a wheelchair, a position where he could see the dealer’s cards. Griffin remembered seeing the same man gambling a few days earlier, only this time he was standing up. He called the security boss. When the man in the wheelchair was approached, miracle of miracles, he leaped up and ran, only to be caught by Griffin.

Because of Griffin’s skills, stockbroker and card counter Ken Uston was thrown out of numerous casinos.

“He dedicated one of his books to us,” Beverly said with a laugh.

She recalled going with her husband to a Caesars Palace tennis event in the early 1980s and sitting in a box near Uston, who was sitting nearby with his friends. It was an opportunity to memorize Uston’s associates’ faces.

Never know when those faces might be worth knowing.

I covered the federal trial of Dennis Nikrasch when he was convicted in 1986 of scamming $10 million by rigging slot machines so his comrades could win jackpots and give him the lion’s share. Beverly credited her husband’s skills for recognizing the jackpot “winners” and helping build the case.

Griffin came to Las Vegas from San Francisco in the 1950s and at 6-feet-4 inches tall, nabbed a job with the Clark County sheriff’s office, where he worked for more than 13 years. Then he formed the private investigation company with Beverly, working for local attorneys and then with the Howard Hughes casinos. He also launched the Griffin Book.

An Associated Press article in 1984 began, “To its many enemies, Griffin Investigations is the ‘unofficial gestapo’ of the casino industry, but to his clients, Bob Griffin is vital to protecting the integrity of casino gambling.”

The Griffin Book started on loose-leaf paper stored in three-ring binders. The paper versions were discontinued when technology allowed the company to use computers. Today, Griffin Investigations has 10,000 people in its database.

Their divorce after 34 years of marriage was prompted when Beverly wanted to move into the computerized world and he didn’t and they began arguing. The company was computerized in 1999 and he retired in 2003.

She remembered how Griffin was once offered double his salary to look the other way when he was in law enforcement and in the early days of their business. He refused.

“We were always the good guys with the white hats,” she said.

Yet with his photographic memory, it could easily have gone the other way.

Jane Ann Morrison’s column runs Thursdays. Leave messages for her at 702-383-0275 or email jmorrison@reviewjournal.com. Find her on Twitter: @janeannmorrison