UNLV astrophysicist writes space symphony to thrust science ahead

Outer space might be silent, but if planets could sing, their tunes could tell us a lot about how they formed.

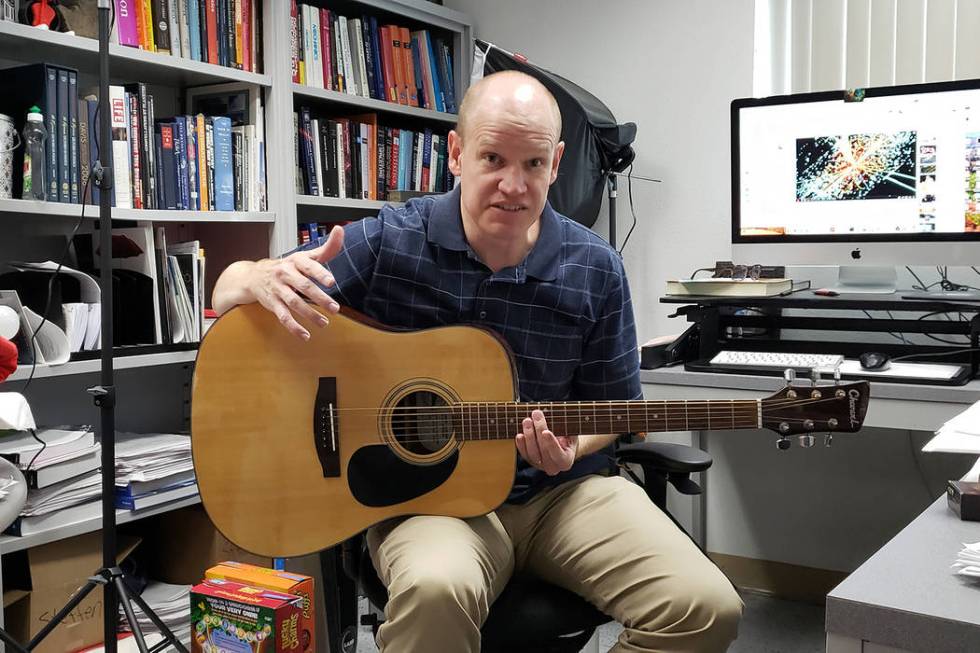

At least that’s the theory of UNLV researcher and astrophysicist Jason Steffen, who turned data on thousands of distant worlds into chord progressions that may indicate how they have changed since their births.

Of particular interest to Steffen are “exoplanets,” worlds orbiting stars outside our solar system, whose signatures produce musically pleasing sounds. He says that indicates that their orbits have been influenced by another planet and that the two are now moving together in resonance.

This can happen when planets change positions during the formation of their systems because of a phenomenon known as planetary migration, Steffen said.

“If it sounds grating, it indicates that there’s been no migration,” Steffen said. “But if it sounds nice, that could mean there was migration, and that gives us insight into the history of that particular system.”

Steffen said he was inspired by a composer who claimed that setting scientific data to music was too simplistic and would not produce any meaningful results.

“I took that as a challenge,” Steffen said.

In planetary science, he said, the relationships between planets’ orbits often take on patterns not unlike those seen in music, an idea first described by medieval philosophers and later expanded on by astronomer Johannes Kepler in 1619.

Steffen demonstrates this for his physics students by pulling out a guitar. A chord in a 2-to-1 ratio is an octave; one in a 3-2 ratio is a perfect fifth.

In our solar system, he said, Neptune and Pluto travel around the sun in a 3-2 formation, meaning Neptune travels three times around the sun each time Pluto travels twice, creating a musical fifth.

Steffen said he wanted to explore how exoplanet systems sounded in order to help parse the cacophony of data coming in from the Kepler space telescope mission, which he worked on for nine years. From the time the telescope launched in 2009 to when it was declared dead in 2018, it detected 2,300 confirmed exoplanets and over 3,000 more unconfirmed “planet candidates.”

Using that data, Steffen spent approximately a day working in the computation system Mathematica to develop a function that could translate relevant information like planet size and orbital period into music. The size of the planet sets the volume of the note, and the base tone is set by the orbital period of the largest planet in the system.

The entire process took about a day, resulting in an 8-minute-long video that sounds like an atonal piano composition.

“My students probably listen to the first minute, say ‘cool’ and then turn it off,” Steffen said.

But he said he hopes that by listening to the song, other researchers can more easily identify worlds that sound interesting, then seek out additional information related to those systems.

“No one has studied the 3,478th system,” Steffen noted. “No one has time.”

Contact Aleksandra Appleton at aappleton@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0218. Follow @aleksappleton on Twitter.