How Nevada deals with end-of-life spending

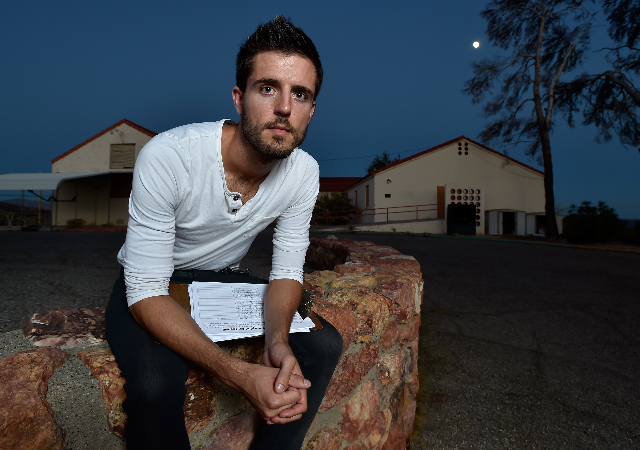

Richard Fields admits he didn’t make the best choice for his dad.

In mid-2013, Fields’ father was living in a Las Vegas nursing home. The widower was 87 and had dementia. Yet when his father began his inevitable slide toward death, Fields stepped in to stop it.

Fields flew in from San Antonio and had his father admitted to a local hospital. After a week — about half of it in intensive care — Fields’ dad was returned to his nursing home, where he died four days later.

“It was an ill-advised action on my part. It was just his time,” Fields said. “I was kidding myself, really. I was grasping at straws. He didn’t have the best quality of life, but he was my father, and I loved him and I wanted to keep him around as long as I could.”

Federal statistics show legions of Nevadans — and Americans — go all-out in the last few months of life, taking desperate medical measures even though death is unavoidable. In the process, patients, their families, their providers and even the medical system suffer immense financial and emotional costs. From hospital invoices that run in the six figures to guilt that can last a lifetime, the final bill is in every way the costliest of all.

Nevada, and Las Vegas in particular, have end-of-life spending issues. The medical industry wants to cure some of those problems, but patients ultimately control the cost left to their families.

Huge costs

About 30 percent of Medicare money is spent on care for patients in their last six months of life, according to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. That comes out to nearly $180 billion on total benefit payments of $597 billion in 2014.

“We’re a death-denying society. We have become so removed from understanding the natural trajectory of conditions that we don’t want to think about something that ends in death, no matter what,” said Miriam Volpin, an assistant professor at the University of Nevada, Reno’s Orvis School of Nursing. Her research focuses on end-of-life care. “We’re a ‘supersize’ country — we think bigger is better than better.”

But if the nation does end-of-life-care wrong, then Nevada gets it even wronger.

In Nevada, 19.6 percent of residents spent seven or more days in intensive or cardiac care in the last six months of life in 2012, well above the national rate of 14.7 percent, according to the Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care.

And local hospitals receive well-above-average Medicare reimbursements for those patients. At the low end, Centennial Hills Hospital Medical Center’s average reimbursement of $47,265 was 17 percent above the U.S. norm of $40,428. At the highest end, North Vista Hospital’s $141,551 average was 83 percent higher.

A multitude of challenges might be driving up end-of-life costs.

Start with health care’s business model here, said Dr. Mitchell Forman, dean of Touro University Nevada, a medical school in Henderson.

The state ranks near the bottom in provider-to-patient ratios, particularly in family medicine and geriatrics, Forman said. Where you have fewer generalists to treat and monitor chronic conditions, you have disjointed care. That can mean tests get repeated unnecessarily, or preventable complications aren’t caught early.

Southern Nevada also attracts swarms of retirees, resulting in a sicker population, Forman said.

Then there’s Nevada’s overall high rate of in-migration, which means fewer people have local family, said Kim Boyer, a certified elder law attorney with Durham Jones & Pinegar in Las Vegas.

“We do see a high number of people without family, and when someone doesn’t have that advocate to state what their wishes are, the law requires that hospitals provide life-sustaining treatment, because life is what we value,” Boyer said.

Pile onto those Nevada-specific factors the broader realities of health care economics and human nature.

“The economics are that the hospital has a new gamma knife, and they have to pay for it. Sending people home is not paying for it,” Volpin said. “So there’s an incentive among organizations because they make more to do more.”

For individual doctors, it’s more about winning the fight.

“It can feel like failure for a provider to say, ‘We could try a third or fourth line of chemo, but it’s not really going to make them better,’ ” Volpin said. “It feels like they’re giving up. We’re a species (that) lives on hope.”

That’s even more the case for family members — even for doctors who understand the odds.

Forman’s mother was diagnosed with terminal cancer 35 years ago at age 71, and developed septic shock after complications from the treatments ruptured her colon. Her physicians gave her a 2 percent chance of surviving, but Forman insisted they do what they could to save her. She languished in intensive care for 10 days before she died.

“Who wants to take that 2 percent chance away from their mother?” Forman said.

Fields echoed that on his decision to try to save his dad against the advice of doctors: “My thought was, if I can get him into the hospital, maybe they can get him back to where he was before the decline started three or four days earlier. And maybe he’ll stay around.”

For families, overseeing the care of a terminally ill relative is both a physical and a psychological weight, Volpin said. The guilt and the second-guessing may never end.

And end-of-life dilemmas “cause incredible moral distress among providers who know what they’re doing is not helpful,” Volpin said.

Some pressures on end-of-life costs won’t subside. Retirees are going to keep moving here, for example.

But other issues could soon see fixes.

Better care coming

Two new medical schools — one run by the University of Nevada, one by Roseman University of Health Sciences — are scheduled to open in 2017 with initial classes of 60 students each. The schools could add to the number of primary-care providers, including geriatricians, who can provide coherent, holistic care, Forman said.

But it’s important that the new schools and existing programs boost training of care for the terminally ill.

“We need to let them know early on about the ethical principles surrounding end-of-life care,” Forman said. “What’s a good death? What’s a bad death? What are we doing by putting them in tubes and in expensive ICUs? Are we going to keep them alive, or improve their quality of life? They have to learn to ask themselves if what they’re doing is medically and ethically justifiable.”

It will help when Medicare next year begins to reimburse doctors for discussing end-of-life care with patients, giving more incentive to have those talks before an illness.

“I think it will help, because it will monetize it,” Volpin said. “To be told, ‘Yes, we will give you money to have this 15-minute conversation,’ that can help. Doctors aren’t going to do it for the money, but at least they will feel like they’re not throwing money away in the process.”

But in the end, the responsibility for that final bill falls mostly to patients and their families.

“The team of health care providers needs to know what the patient’s wishes are,” Forman said. “When they don’t know, they become very aggressive.”

That’s why Boyer urges all clients to have health care directives stating their preferences in the event of a terminal illness or incapacitation. They should also designate a durable power of attorney for health matters, and make their choices clear.

“Not very many people say they want heroic measures at the end of life,” she said. “They want to minimize suffering when there’s no hope.”

Boyer said she sees more families writing into their medical directives hospice and palliative care, which focus on managing discomfort at the end.

That’s a good thing, Forman said.

“If you’re not going to change the eventuality, the patient may just want to focus on pain management,” he said. “They may want to control symptoms so they won’t be nauseated or short of breath. Or they may want to have their depression and anxiety managed.”

It’s not always enough to simply have a health care directive, though. Loved ones need to know — or remember in a crisis — that it exists.

Both Fields’ mom, who died in 2005, and his dad had prepared living wills with medical directives through Boyer’s offices. But in the mental and emotional fog that hovers over the death of a close family member, he forgot about those instructions.

“I wasn’t thinking clearly then. I was so upset. But I hauled (the living will) out later, and it said he didn’t want to be kept alive artificially, and that’s exactly what I did.”

Fields said what happened to him “probably goes on more frequently than it should.”

“People should have that conversation. It’s difficult for sure, but it’s something they need to do.”

Contact Jennifer Robison at jrobison@reviewjournal.com. Follow @_JRobison on Twitter.