PART 3: Colorado River’s decline poses long-term risks for Southern Nevada

t supplies water and power to 40 million people from Wyoming to Mexico and irrigates billions of dollars in cropland used to feed millions more.

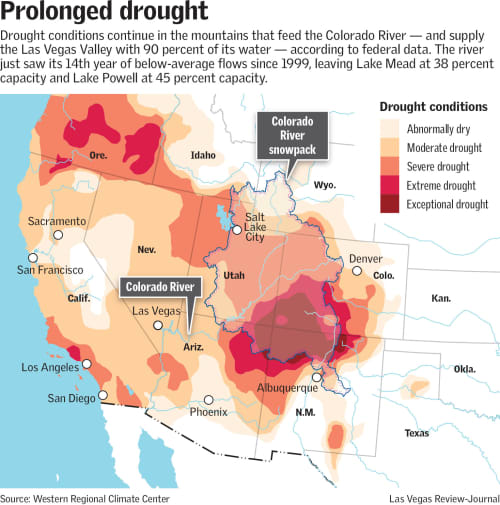

No wonder so many people are worried about the Colorado River. Punishing drought has ravaged the system for almost 20 years, shrinking its two largest reservoirs to a record low 40 percent of combined capacity.

A bleached bathtub ring 130 feet tall marks the decline of Lake Mead, which supplies 90 percent of the water used by nearly three-quarters of Nevada residents. That white stripe on the cliffs surrounding the nation’s largest reservoir is expected to grow another 30 feet over the next two years as farms and cities downstream continue to divert more water than the Colorado can reliably provide.

The "bathtub ring" is seen on the rocks in the background as people visit the Hoover Dam at Lake Mead National Recreation Area in October 2018. (Richard Brian/Las Vegas Review-Journal)

The current dry spell has gone on so long in the mountains that feed the river that researchers have begun to describe it with words like “megadrought” or worse. Some argue we could be witnessing the river’s “new normal” in a warming world.

The seven Western states that draw water from the river face a federal deadline of March 19 to submit plans to voluntarily trim their use ahead of a federal shortage declaration expected this year, which would force deeper cuts designed to keep Lake Mead from crashing.

Brad Udall, a senior water and climate scientist at Colorado State University, has written extensively about the impacts of climate change on the river. A 2017 study he coauthored with climate researcher Jonathan Overpeck charts a 20 percent decline in the Colorado’s flow since 2000, with at least a third of those losses directly tied to rising temperatures and increased evaporation.

“That’s the link to climate change, and it’s pretty apparent,” Udall said. “Losses like that year in and year out is what leads to the edge of the cliff we’re standing on.”

Doomsday preppers

Water officials in Las Vegas insist they are ready for whatever the drought dishes out at Lake Mead — or they soon will be.

Workers pump concrete for the third water intake structure near Saddle Island at Lake Mead in November 2010. (Review-Journal File)

All it took was $1.47 billion in construction bonds, which water customers and taxpayers will be paying off for decades through service charges, connection fees and a quarter-cent sales tax.

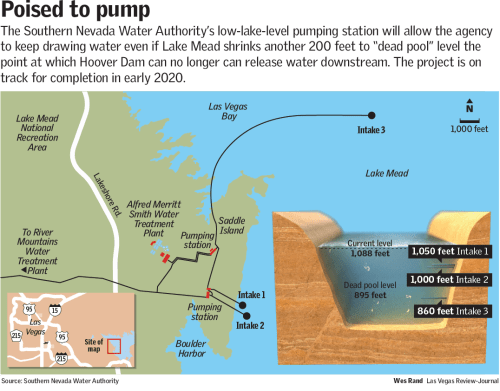

In 2008, the Southern Nevada Water Authority started construction on a third straw at Lake Mead, one designed to keep water flowing to the Las Vegas Valley should the lake drop low enough to shut down the community’s two older intakes.

A worker is raised from the tunnel system for the third intake at Lake Mead in June 2013. (Review-Journal File)

The 3-mile, $817 million tunnel to the deepest part of the reservoir was finished in 2015 and will soon be paired with a low-lake-level pumping station on track for completion in April 2020. That $650 million project will allow the authority to continue delivering Nevada’s full allocation of Colorado River water even if Lake Mead shrinks another 190 feet to “dead pool” level, the point at which water can no longer be released downstream through Hoover Dam.

Authority General Manager John Entsminger said those two infrastructure investments essentially make the community “immune from the drought cycle.”

“We did that before anybody else was really talking about how bad the conditions in the lake could get. And because we moved fast, we’re now … in a great position to weather some of the more dire predictions that are coming out about the Colorado River,” he said. “I think the worst-case scenario is that we continue to see declines in inflow into Lake Mead, and the basin states and Mexico don’t do anything about it. Fortunately, the worst-case scenario for us still has us able to take our water out of the lake.”

Getting shorted

If access to water won’t be an issue for Southern Nevada, the total amount available eventually might be.

The continued decline of Lake Mead will trigger a series of cuts by Nevada, Arizona and California, the first of which is on track to hit Jan. 1 with the expected first-ever federal shortage declaration.

Though the community has reduced water use enough over the past 15 years to absorb any cuts expected in the near term, years of sustained shortages would make it increasingly difficult for Southern Nevada to find the water it needs for future growth.

“Our state is on the brink of a water crisis and, as our communities in Southern Nevada continue to grow and thrive, this crisis will only worsen,” Gov. Steve Sisolak said in a written response to questions from the Review-Journal. “There’s no question that we need a 21st-century solution to Southern Nevada’s water supply issues in order to keep up with the exciting growth that region has seen over the last several years.”

Structural deficit

The drought has exacerbated a fundamental problem on the Colorado: In the 1920s, when representatives from seven Western states met to decide how much water everyone would get, the river was in the midst of one of its wettest periods in the past 1,200 years. As a result, the states ended up with rights to significantly more water than the river actually provides.

“The 20th century gave us about 15 million acre-feet a year,” Entsminger said. “Under climate change scenarios, I think we need to be prepared for … only getting an average of 11 or 12” million acre-feet.

A bird perches on the remnants of some boating equipment near Lake Mead Marina at Lake Mead National Recreation Area in October 2018. (Richard Brian/Las Vegas Review-Journal)

This is why many water managers see little point in tearing up the almost-century-old compact that controls who gets what and reapportioning the river to better reflect where the greatest needs are today.

Pat Mulroy, former general manager of the water authority, said no one is likely to benefit from renegotiating the so-called law of the river. Everyone would get less, Mulroy said, assuming a new deal could even be reached without a protracted legal fight.

“It takes seven legislatures to approve it, seven governors to sign it, Congress to ratify it and the president to sign it,” she said. “How long’s your life? I mean, what state is going to give up their birthright?”

Mulroy believes the only way forward is for the states to keep doing what they’re doing: work together within the river’s regulatory framework and keep themselves out of court.

Water historian Christian Harrison is less optimistic.

“I think collegiality is working for now,” he said, but what happens as the Colorado continues to shrink and demand outstrips supply in parts of the basin that have grown dramatically since the river was parceled out in the 1920s?

“I’m not a fan of the approach where we do it sector by sector ... My constituents take showers in Las Vegas, but they eat hamburgers that are fed by alfalfa grown in the Imperial Valley, and they like the idea … of maybe taking a rafting trip down the Grand Canyon at some point.

John Entsminger, Southern Nevada Water Authority General Manager

Take Wyoming, for example: It is now the nation’s least populous state, with about one-fifth the population of Nevada, but its annual share of the Colorado is three times larger than the Silver State’s.

“How can anyone justify that?” Harrison asks.

Down on the farm

Farmers have the most to fear from a diminished river, Udall said. Since roughly 80 percent of the water diverted from the Colorado is used to grow crops, he said, the “real crisis” and biggest opportunity for change lies with the agriculture sector.

A buoy marks the restricted area to the Hoover Dam intake towers along the Colorado River's Black Canyon at Lake Mead National Recreation Area in October 2018. (Richard Brian/Las Vegas Review-Journal)

But Entsminger believes no one group of water users should be made to shoulder all the pain.

“My constituents take showers in Las Vegas, but they eat hamburgers that are fed by alfalfa grown in the Imperial Valley, and they like the idea … of maybe taking a rafting trip down the Grand Canyon at some point. So those are false distinctions in my mind,” he said. “I think we have to look at this river as a whole, realize that everyone in every sector has to use less water, and figure out partnerships between those different entities.”

Entsminger sees opportunities for cities and farms to work together on exchanges and efficiency improvements that will benefit everyone by freeing enough water to keep the river healthy while allowing continued — if sensible — development across the basin.

Udall fears the climate might have other ideas.

“This 19-year drought is starting to look like some of the megadroughts we’ve seen in past centuries,” he said. “The challenge facing the Colorado is far greater than at any other time in its development.”

(Wes Rand/Las Vegas Review-Journal)

Entsminger harbors no illusions about what lies ahead.

“I think the future of the Colorado River is everybody who uses the river using less of it,” he said. “I think there are absolutely going to be years when there are shortages on the river, and everybody is going to have to come together to figure out how to deal with those.”

What gives him hope is what he has seen so far: an unprecedented level of interstate and international cooperation on the river and a commitment by valley residents to conserving water and investing in infrastructure.

“I think the tools are there to handle this,” Entsminger said. “I don’t think this has to be a crisis.”

Contact Henry Brean at hbrean@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0350. Follow @RefriedBrean on Twitter.