COMMENTARY: How did Latin America’s wealthiest country fall so far?

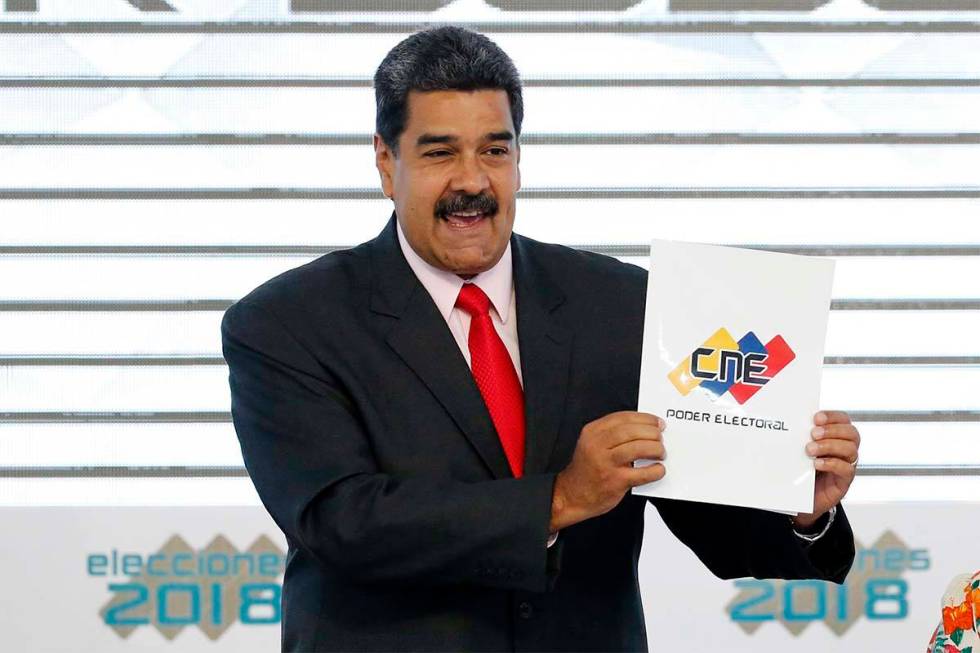

In 1970, Venezuelans were the wealthiest people in Latin America. With annual incomes comparable to those of the Finns and the Japanese, they earned two-and-a-half times what the typical Latin American earned. Their wealth bought them a longer life, lower infant mortality and some measure of safety. Today, as the United Socialist Party’s Nicolás Maduro tries to steal another term as president, it is a different story.

The typical Venezuelan earns one-third of what the typical Latin American earns and one-seventh of what the Japanese and the Finns make. According to the United Nations, 90 percent of Venezuelan households are impoverished, and 7.7 million people have fled the country.

The annual inflation rate is 160 percent, which sounds terrible until you hear it reached 130,000 percent a few years ago.

What happened?

Venezuela’s past prosperity was a product of good luck and decent policy. On the side of luck, the Earth’s largest known oil reserves were discovered in northwestern Venezuela in 1914. The gush of oil fueled a post-World War II boom, and Venezuela’s private sector thrived.

As for decent policy, the Venezuelan government of the mid-20th century knew enough not to kill the goose that laid the golden (black) egg. Its spending was restrained, and its taxes were low. It allowed most industries to remain in private hands. The Central Bank of Venezuela kept inflation below its 2 percent to 3 percent target for half a century. With some of the lowest tariffs and barriers to trade, Venezuelans were free to buy from whomever they wished, importing fancy cars and other luxuries while exporting about a million barrels of oil to the rest of the world daily.

It wasn’t perfect. The regulatory burden made it difficult for Venezuelans to start and run businesses, and the legal system didn’t always protect people and their property. But overall, Venezuelans could make most of their own economic choices without interference from others. According to the Fraser Institute’s Economic Freedom of the World report, theirs was the 14th-freest economy in the world in 1970.

The seeds of today’s disaster were already being sown. In 1976, the Venezuelan government nationalized the oil industry, creating the state-owned company Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA). For decades, PDVSA was allowed to operate as if it were a private business, relatively free of state interference. However, when public and private interests are combined, the temptation for corruption is enormous, and this fateful decision eventually turned Venezuela into a petrostate.

In the meantime, the government increasingly curtailed the economic freedom of ordinary Venezuelans. By 2000, the country had slipped to 107 out of 127 countries in Fraser’s economic freedom ranking. Venezuelans were earning less than they had in the 1970s.

Then came Hugo Chávez. At first, the populist offered more of the same. With time, he grew more radical. Under the banner of “Socialism of the 21st Century,” he promised a new and better society by doubling down on the policies that had already begun to impoverish his people.

He tightened the government’s grip on PDVSA, inviting rampant corruption. He nationalized other industries, including iron, steel, cement, mining, farming, food distribution, grocery chains, banking, hotels and telecommunications. He increased spending and borrowing and turned to the printing press to finance growing deficits. Then, as inflation heated up, he attempted to mask it through price controls.

As the country plummeted to the bottom of the economic freedom rankings, more than a few Western intellectuals were taken in by the brash dictator and his radical policies. Oil prices were booming, so the country’s economy gave the appearance of muddling through. However, the results are bleak when economists compare Venezuela’s performance under Chávez with that of similar countries.

Ever the showman, Chávez exited the scene just before things came undone. He died in March 2013, and within months, price controls had yielded predictable shortages of household necessities. His successor, Nicolás Maduro, presided over the aftermath: hyperinflation, collapsing incomes, skyrocketing poverty, a refugee crisis, and today, a stolen election.

The only hope for Venezuela is a return to decent policy.

Matthew D. Mitchell is a senior fellow with the Fraser Institute, a senior research fellow with the Knee Center at West Virginia University and an affiliated senior scholar with the Mercatus Center at George Mason University. He wrote this for InsideSources.com.