DEBRA J. SAUNDERS: Epstein case still used to smear Acosta

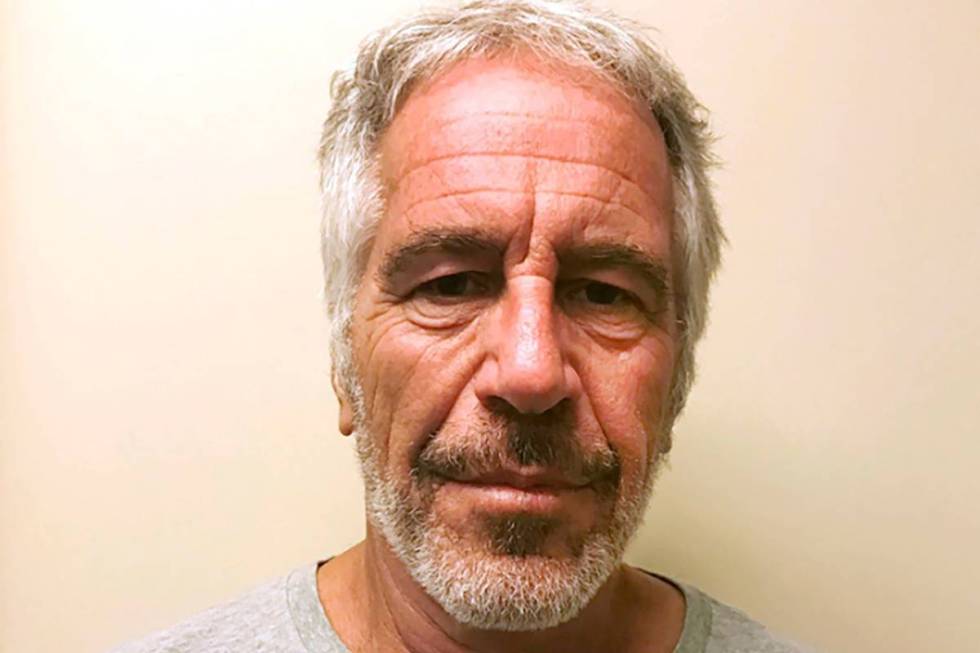

WASHINGTON — Before he was found dead in a New York jail cell in what a coroner described as a suicide, Jeffrey Epstein was a super-rich serial sex abuser with impeccable political connections and a ruthless streak. A year after his death, Epstein haunts a criminal justice system that failed his many victims.

In 2005, the parents of a 14-year-old girl complained to the Palm Beach Police Department in Florida that Epstein had paid their daughter for a massage. The investigation led to the discovery that Epstein used personal assistants to recruit girls to provide massages for him and the massages often led to sexual abuse.

After the state attorney’s office presented its case, a grand jury indicted Epstein for a felony count of solicitation of prostitution. In search of a tougher, more appropriate sentence, local law enforcement reached out to the FBI in the hope that the feds could come up with charges that better reflected Epstein’s crimes.

In 2007, the U.S. attorney for the Southern District of Florida, Alex Acosta, issued a 53-page indictment.

Enter Epstein’s dream team of lawyers, which included Alan Dershowitz of O.J. Simpson trial fame; Roy Black who won an acquittal on a rape charge for William Kennedy Smith, JFK’s nephew; and Ken Starr, who served as special counsel against President Bill Clinton.

As Acosta later wrote, Epstein’s lawyers investigated federal prosecutors and their families “looking for personal peccadilloes,” which they tried to use to disqualify at least two prosecutors.

The prospect of putting vulnerable teenage victims on the stand to testify before well-paid sharks waiting to shred their credibility — that made it easy to see that Epstein might be found not guilty.

So Acosta worked on a non-prosecution agreement that required Epstein to plead guilty to felony solicitation of prostitution and procurement of minors for prostitution in state court. Most important, the deal required that Epstein register as sex offender, agree to a minimum of two years behind bars, later reduced to 18 months, and pay restitution.

It was not the harsh sentence Epstein deserved, but it beat acquittal. At least, as Acosta later argued, the arrangement “put the world on notice” that Epstein, a friend of sorts to powerful men such as Prince Andrew, Clinton and real estate developer Donald Trump, “is a sexual predator.”

After pleading guilty in 2008, Epstein gamed local law enforcement. He applied for the Palm Beach County sheriff’s work-release program. For no good reason, his application was approved — which meant Epstein spent 12 hours a day, six days a week at his private office. No wonder critics called it a sweetheart deal.

After his time was served, Epstein returned to his lifestyle of the rich and famous. Yes, he was a registered sex offender. Still, he lived large and largely avoided the interest of the press.

Prosecutors elsewhere, such as in New York, where Epstein owned a home, were not bound by the Acosta deal, but none charged him.

Then in 2017, Trump, now president, picked Acosta to be his Labor secretary. Only then did the Miami Herald take a long look at the Epstein saga and produce the 2018 series “Perversion of Justice.”

Only after the story was hot news in 2019 did New York U.S. Attorney Geoffrey Berman indict Epstein for sexual exploitation with minors — between 2002 and 2005.

Cable news applauded Berman for taking action, more than a decade late. Acosta, the only prosecutor to put Epstein behind bars, was hounded from his job. For his troubles, Acosta got a bonus: a federal investigation into his handling of the case.

Guess what: The department found no prosecutorial misconduct, although it did say the plea deal constituted “poor judgment.” Considering what followed with the Palm Beach Sheriff’s Office, who can argue?

“Of course, had Secretary Acosta known then what he knows now, he certainly would have directed a different path,” Acosta reacted in a statement. Back in 2008, his office did not know about “allegations of foreign travel, physical force or violence; “rather, victims went to Epstein’s home, were victimized and returned to their own homes, all in Palm Beach County. The Epstein case understood today is vastly more sweeping than what was understood in 2008.”

It is an outrage that Epstein was able to prey on vulnerable teens for a decade after his guilty plea. But there’s something wrong with targeting the only prosecutor to put Epstein away, especially when so many in power looked the other way for a decade.

Contact Debra J. Saunders at dsaunders@reviewjournal.com or 202-662-7391. Follow @DebraJSaunders on Twitter.