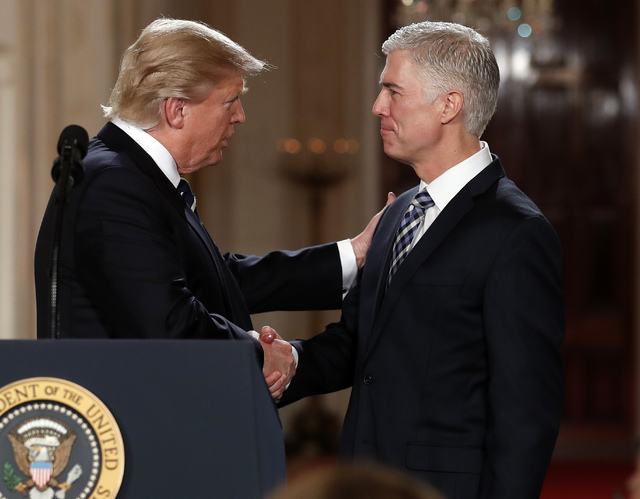

Neil Gorsuch nomination to Supreme Court offers peril for both Republicans and Democrats

Of all the phrases associated with modern politics, none may be as bitter as “elections have consequences.”

A taunt from the winner, a bitter pill for the loser, it conveys a sense of entitlement for a victor’s agenda, regardless of how narrow the margin.

As the Senate prepares to take up President Donald Trump’s nomination to the U.S. Supreme Court of Judge Neil Gorsuch, Democrats will hear that phrase often.

It shouldn’t come as a surprise; on the campaign trail, Democrat Hillary Clinton repeatedly invoked Supreme Court appointments as an argument for her candidacy.

Democrats will undoubtedly feel bitterness, especially given the vacancy that gave rise to Gorsuch’s nomination occurred under President Barack Obama, whose eminently qualified nominee to the court was ignored by Republicans in an unprecedented rebuke. Already, the idea that Gorsuch has been nominated to a “stolen seat” is gaining currency.

A bit of unsolicited advice for Republicans, especially Nevada’s senior senator, Dean Heller: Be cautious about following Trump’s advice to eliminate the 60-vote filibuster for Supreme Court nominees. It may seem awfully convenient now, but at some future time, when your party is in the minority, you will regret it, just as Democrats no doubt regret their loosening of the rule on Cabinet and lower-court appointees. A consensus nominee should get at least 60 votes.

Another piece of unsolicited advice for Democrats, especially Nevada’s Sen. Catherine Cortez Masto: Remember the Senate’s “advice and consent” function is about whether the nominee is qualified for the job.

That’s a far different question than, “Does the nominee agree with us on the issues?” or, “Will the nominee rule the way we think he should?” It’s different than questions from Democrats about whether the nominee is “mainstream.” (Translated: Is he a liberal?)

Gorsuch is many things, most quite impressive. He’s a Harvard Law School graduate. He holds a doctorate from Oxford. He won unanimous Senate confirmation to the 10th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. He’s said to be principled (in the same originalist philosophy as the justice he’s meant to replace, Antonin Scalia) but less combative. His style is more of a conversation, in which he listens to those with whom he disagrees.

He’s not, however, a liberal. This should also come as no surprise, since Trump repeatedly promised to nominate justices in the mold of Scalia.

There are plenty of things in Gorsuch’s record with which Democrats will disagree. His ruling in the Hobby Lobby v. Sebelius case, in which he found a corporation enjoys the First Amendment right to free religious practice, is one. But that’s hardly Gorsuch’s fault. He was simply applying a pernicious bit of 1990s triangulation ironically known as the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, the handiwork of the late Ted Kennedy and then-Rep. Charles Schumer, signed into law by Bill Clinton.

But Gorsuch’s record also shows a penchant for independence, including a case in which he rejects the notion that federal government agencies are due deference in how they interpret the law. Gorsuch believes, as the Madison v. Marbury court did, that it is the province and duty of the judicial department to say what the law is.

Given his qualifications, and absent a disqualifying revelation during hearings, it will be difficult for Democrats to reject Gorsuch, at least on defensible grounds. Revenge for past GOP slights and differences over interpretation of the laws are not among them. For the good of the Republic, Democrats should endeavor to be dissimilar from the Republicans who scuttled Obama’s nomination.

Why? Elections do have consequences. The proper way for Democrats to correct the nation’s course comes in four years, at the ballot box.

Steve Sebelius is a Review-Journal political columnist. Follow him on Twitter (@SteveSebelius) or reach him at 702-387-5276 or SSebelius@reviewjournal.com.