State’s best-funded schools are in poorest neighborhoods

If lawmakers are serious about equity in education funding, they‘ll increase school spending in Nevada’s richest neighborhoods.

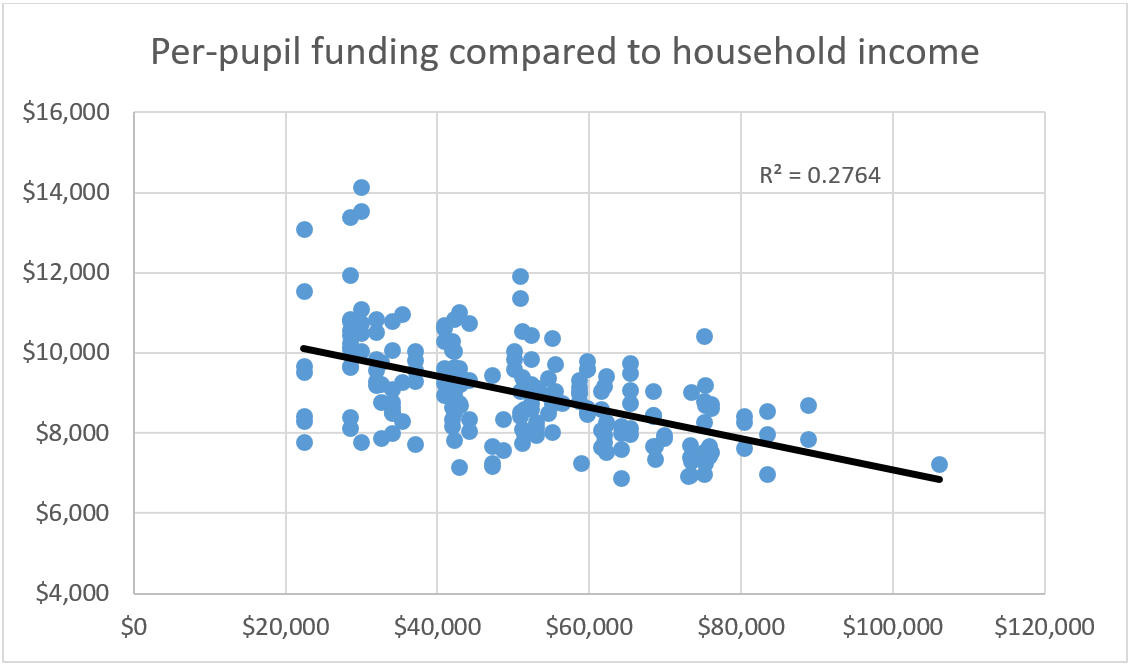

The highest-income neighborhoods in Clark County receive far less school funding than poorer areas. An analysis of spending at the Clark County School District’s more than 200 elementary schools reveals an inverse relationship between household income based on ZIP code and the funds schools receive.

Put simply: As parents earn more and pay more taxes, the schools their children attend get less.

At Stuckey Elementary in Southern Highlands, where the median household income is $83,470, the school gets $6,986 per student. At Fitzgerald Elementary in downtown North Las Vegas, where the median household income is $28,486, the school receives $13,391 a student.

Listening to legislative leaders discuss equity gives you the opposite impression. Senate Majority Leader Aaron Ford and Assembly Speaker Jason Frierson penned an op-ed recently calling for “equitable access” to public schools.

In his State of the State response, Ford elaborated: “We know we have more challenges within our public school system to ensure we give our kids the resources and the opportunities they deserve, regardless of the neighborhood they grew up in or the size of their parents’ paycheck.”

Equity has become the latest buzzword in the education establishment’s never-ending quest for more of your money. In most states, schools in rich neighborhoods do receive more funding.

Nevada isn’t most states. We have the fewest school districts, 17, of any state in the lower 48. Most states have hundreds. For instance, there are 639 school districts in New Jersey, which is just 10 percent bigger by land area than the Clark County School District.

In those states, property taxes from wealthy neighborhoods stay in a local school district and go back to schools in those neighborhoods. The rich get richer, while the poor get poorer, as families desperately try to get into affluent school districts, driving property values and property tax collections even higher.

In Nevada, property tax revenues are centralized at CCSD’s marble palace on Sahara Avenue, and money from wealthier areas goes to poorer areas.

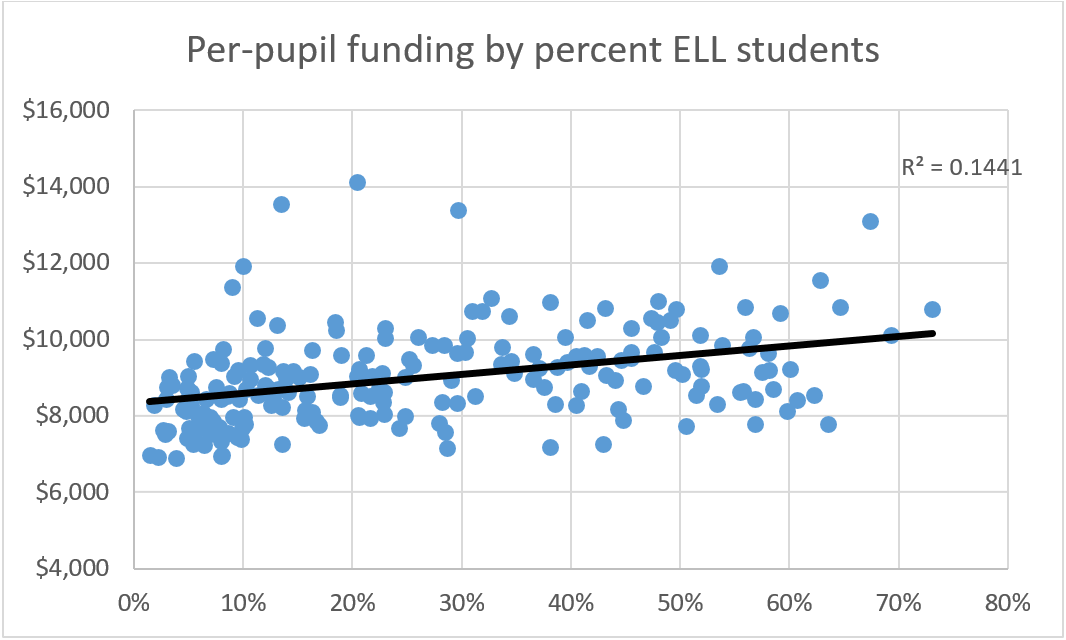

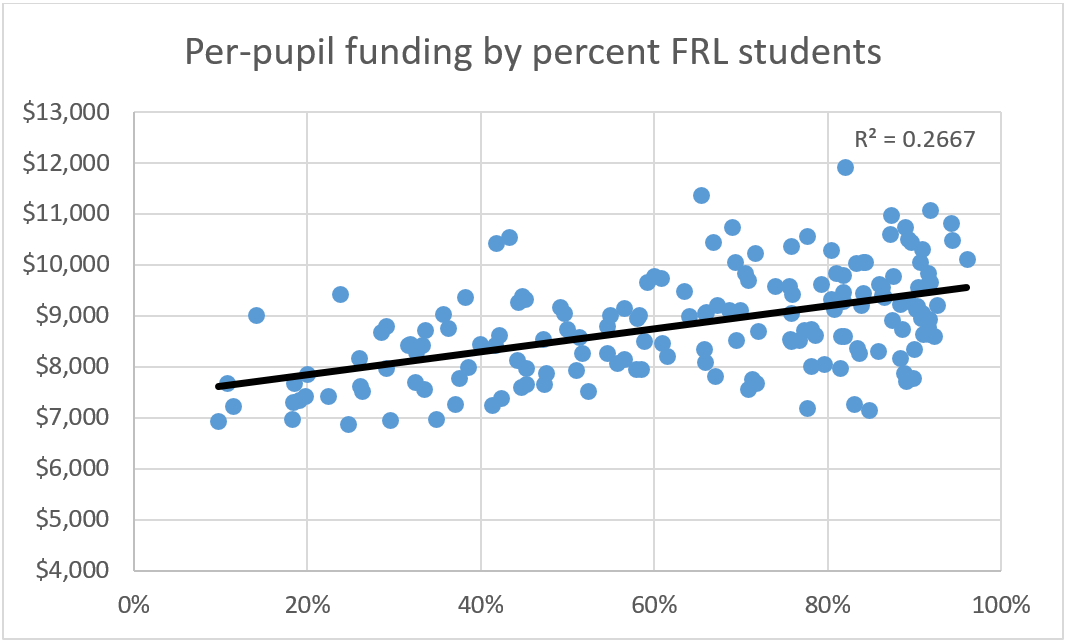

This happens in part, because the district spends more at schools with large populations of students eligible for Free and Reduced Lunch, a 26 percent positive correlation with higher spending, and ELL students, a 14 percent positive correlation with more funds.

The school district doesn’t need $600 million more to create the weighted funding formula that’s needed for its reorganization plan. It already distributes funds unequally.

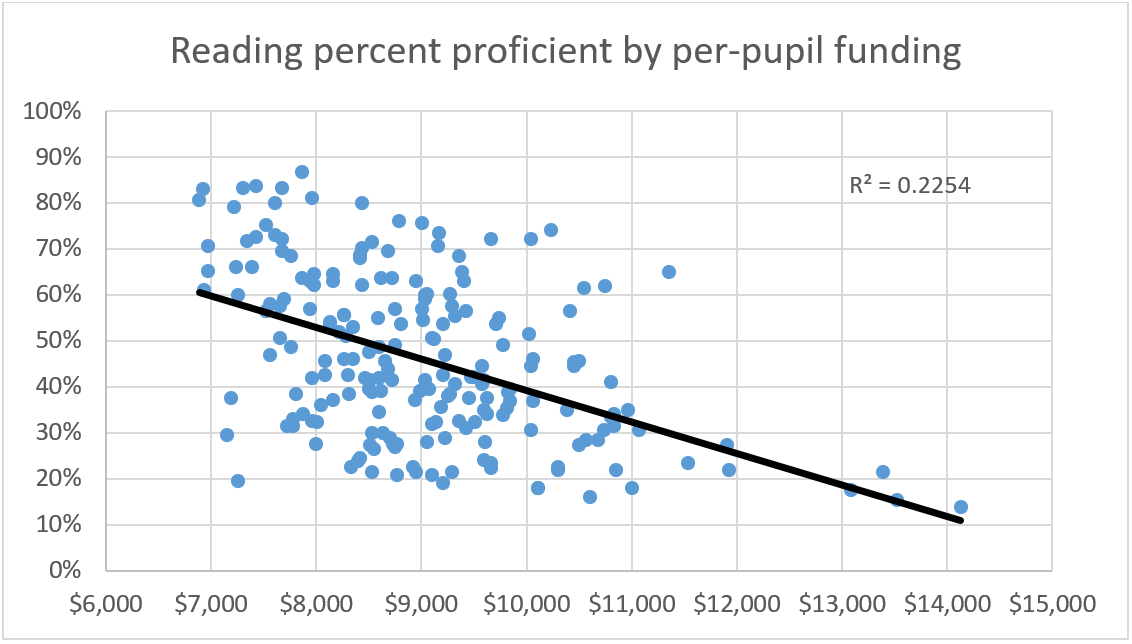

Don’t expect funding discussions to increase student achievement, however. As a Review-Journal column revealed in 2012, our best-funded schools are the worst performing, and that trend continues today.

All data come from the District Accountability Report and NevadaReportCard.com. The usual caveats about “correlation not equaling causation” apply, but these facts should give lawmakers pause.

Before a politician trots out the “equitable funding” talking point again, he or she should understand what equity would actually entail.

Victor Joecks’ column appears in the Nevada section each Monday, Wednesday and Friday. Contact him at vjoecks@reviewjournal.com. Follow @victorjoecks on Twitter.