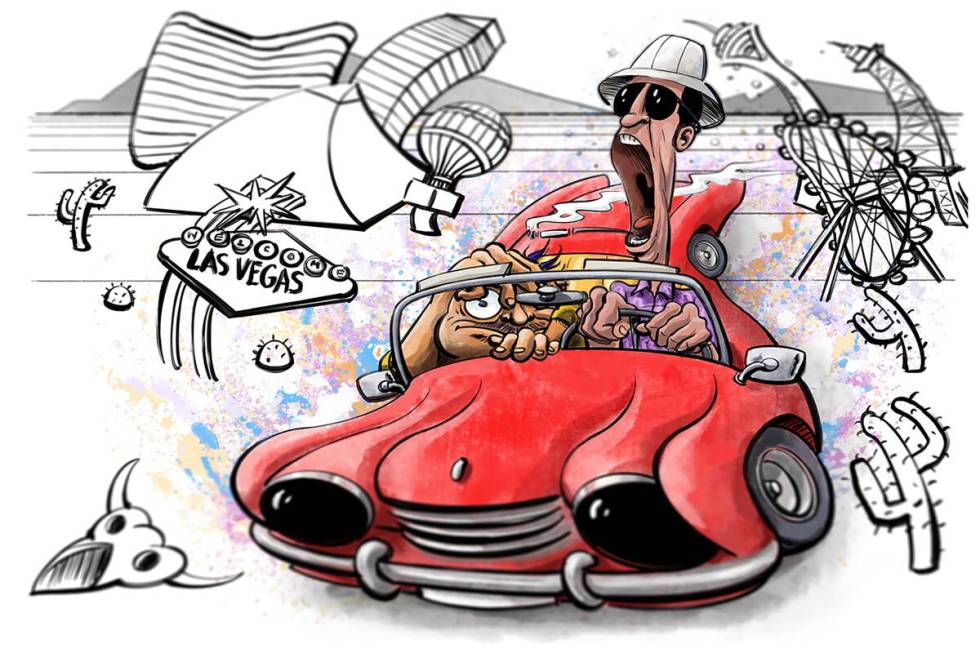

‘Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas’ turns 50. Cue the reptile people.

The lizard people have left Las Vegas. The blood they spilled on the carpet of the Desert Inn is long gone — along with the hotel itself. The merry-go-round, though, is still here — even if it goes round no more, idling on the casino floor of Circus Circus, filled with Jumping Jalapeno penny slot machines in place of painted horses. The trapeze artists also remain — an aerialist in a bedazzled blue get-up tucks her heels behind her ears on a Thursday evening, pretzeling her body above the poker tables below.

Fifty years ago, this place, these scenes, were immortalized by an ether-addled journalist and his sidekick, a Samoan lawyer who wasn’t really Samoan, in a pair of Rolling Stone magazine articles that became a fever dream of a book: “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas.”

In 200 acid-enhanced pages, an era, a generation and a city were encapsulated, satirized and embalmed in a timeless sign of the times, Vegas the lurid landscape upon which it all takes place.

“We came out here to find the American dream …” Thompson wrote, frying on mescaline and scaring the staff at Circus Circus. “You must realize that we’ve found the main nerve.”

Thompson touched that nerve — tap-danced on it, really — while turning Las Vegas into both a symbol and a caricature of said dream.

“Thompson depicted Las Vegas as the pit of hell, a gambler’s Disneyland, a place of extreme, hallucinatory fantasy without limits — so it became a legendary symbol (displacing Chicago, Miami and New York City),” explains Kevin T. McEneaney, author of “Hunter S. Thompson: Fear and Loathing and the Birth of Gonzo.” “Politicians know that bad publicity is better than no publicity. Thompson put Las Vegas on the map of domestic and international tourism!”

And he did so in a manner that endures to this day — for better and, as is often the case in “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas,” for far, far worse.

It’s a wild trip, man, stock up on the antacids.

“Buy the ticket, take the ride,” Thompson advises in the book, “and if it occasionally gets a little heavier than what you had in mind, well … maybe chalk it up to forced consciousness expansion.”

Tune in, freak out, read on …

‘Horatio Alger gone mad on drugs in Las Vegas’

The American dream had become a nightmare.

At least for Hunter S. Thompson.

In the wake of the success of his 1967 book “Hell’s Angels: The Strange and Terrible Saga of the Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs,” where Thompson embedded himself in said gang, he inked a deal with Random House for a series of follow-up books.

“One of them was supposed to be a nonfiction book about the American dream, and he couldn’t finish it,” says Peter Richardson, author of the forthcoming book “Savage Journey: Hunter S. Thompson and the Weird Road to Gonzo.” “He was three years overdue. It wasn’t coming together; he had still yet to invent gonzo. He was really struggling with it.

“He wrote a long letter to his editor,” he continues, “saying that his manuscript — he had hundreds of pages — was ‘a heap of useless (expletive).’ So, he didn’t really combine that idea of the American dream topic with Vegas until he got to Vegas.”

Thompson didn’t come here to write a book, initially

Instead, he was hired by Sports Illustrated to pen a 250-word caption to accompany photos of the Mint 400 off-road motorcycle race.

Thompson turned in 2,500 words; Sports Illustrated turned him down.

“He was irate,” Richardson says. “Instead of dropping it, he decided to double down and expand that piece and sell it to Rolling Stone. He still had this nonfiction book on the American dream that he needed to write, and he was so angry about the Sports Illustrated rejection that he decided to just keep going with it and make it even longer and crazier and more like a novel, really.”

Written in two parts, the book uses both the Mint 400 and a convention of drug enforcement officers as jumping-off points to explore the ongoing ramifications, the fallout from a jarring generational shift: the end of the flower-power optimism of the ’60s — amputated clean by the Manson murders and the Altamont festival disaster in 1969 — and the cloud-covered onset of the ’70s with Richard Nixon in office, the Vietnam War cleaving the nation into warring factions and Watergate further darkening the horizon.

Thompson blurs the line between fiction and nonfiction as he uses “Fear and Loathing” as a billy club against what he perceives to be the failures of the counterculture to sustain its utopian ideals, the tide of change receding into a sea of stasis.

“You can go up on a steep hill in Las Vegas and look West, and with the right kind of eyes you can almost see the high-water mark—that place where the wave finally broke and rolled back,” he writes of the counterculture’s recession.

Las Vegas, then, is the place where the American dream gets turned on its head, an ugly scene populated by ugly, drug-induced characters — cue the reptile people!

“This whole idea that if you work hard you will be successful, this Horatio Alger dream or myth that he describes in the book, plays out perfectly well in Las Vegas in an upside-down sort of way,” says Gregory Borchard, a UNLV journalism professor who’s taught classes on the works of Thompson. “The people who come here aren’t planning on working hard, they’re planning on having a good time and they’re still, at the same time, planning on being successful, because if they get lucky on the slot machines, they put in a dollar and you can make a million dollars. It’s the opposite of this classic American dream idea.”

Vegas, then, not only embodies this idea, but also its decay, the rot beneath the neon.

“It’s the perfect irony that’s woven into the text, with the baby boomers specifically in mind, I think,” Borchard elaborates. “The baby boomers had this tremendous idealism in the early ’60s, all the way up until the late ’60s, where they thought they could change the world, and it all came to this crashing halt and they got really, terribly cynical and disillusioned and burned out.

“It was that loss of idealism that, for Thompson, represented the death of the American dream,” he continues. “And what better place to describe all that happening than good ol’ Las Vegas?”

‘How long can the brain and body tolerate this doom-struck craziness?’

He was skeptical of everything, his own line of work, even.

“Journalism is not a profession or trade,” Thompson writes in “Fear and Loathing.” “It is a cheap catch-all for (screw-ups) and misfits.”

One of the most prevalent themes of the book is a deep distrust of institutions and authority figures of every stripe, from elected officials to the police to organized religion to some of the very news outlets that Thompson worked for upon occasion.

Fifty years later, this deep suspicion of some of the bedrock components of American society remains more palpable than ever in the minds of some, from the questioning of presidential election results to doubts over FDA-approved vaccines to armed insurrections at the nation’s capital.

Times change — unless they don’t.

“Everything in ‘Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas’ is still relevant today, except the cars we drive,” McEneaney argues. “That is why it is a great classic of American literature. The debacle of the Afghan war repeats the horror of the Vietnam War. Aggressive police brutality retains durability. Ignorance remains as prominent as ever. Phoniness in journalism and some media platforms perpetuates paranoia. Just as the American public was ignorant and paranoid about drugs at that time, they are ignorant about vaccines and ignorant of how elections have been safeguarded.”

“Fear,” then, remains a relevant read — sometimes disturbingly so.

It also lives on as the apotheosis of gonzo journalism.

Thompson had written in this highly immersive, first-person style before, most notably in “The Kentucky Derby Is Decadent and Depraved,” his dive into the titular sporting event published in 1970 in the short-lived Scanlan’s Monthly.

But at that time, Thompson was still balancing his early forays into the gonzo style with more straightforward writing and reporting.

“He doesn’t want to publish the Las Vegas stuff with his straight journalism because he thinks it will hurt his credibility; he still hasn’t realized that the gonzo thing is his most valuable literary asset,” Richardson says of the birth of “Fear and Loathing.” “It just starts as a kind of an accident, and then it turns into a kind of improvisation, and then it turns into this wild comic novel and maybe the most gonzo thing that he ever published.

“Then, only after that, does he realize that gonzo is his meal ticket,” he continues, “that he shouldn’t be distancing himself from it, he should be embracing it.”

‘In Las Vegas, they kill the weak and the deranged’

Las Vegas can be an acquired taste — like bourbon, or battery acid.

For Thompson, the city bore the latter flavor.

“A little bit of this town goes a very long way,” Thompson wrote. “After five days in Vegas you feel like you’ve been here five years. Some people say they like it — but then some people like Nixon, too.”

Thompson often took his ire out on Las Vegans themselves, from terrorizing hotel maids to pulling knives on waitresses to continuously characterizing the people who live here in the most degrading, do-anything-for-a-buck terms.

“The only bedrock rule is Don’t Burn the Locals,” he writes of the city — and then proceeds to immolate them with words ablaze with condescension and contempt.

Plenty of “Fear and Loathing” holds up over the years; that aspect of the book most certainly doesn’t.

“The one thing that really started to grind on me after years of doing this book for class — and the students, too — was how he described and depicted the locals in Las Vegas, the workers on the Strip,” Borchard says. “He had the most disparaging descriptions of these people.”

It’s ironic, in a way: The town that Thompson lampooned so viciously at times ended up becoming central to his career.

“I think Las Vegas is a super important site for him,” Richardson says. “I think he comes into it thinking of it as kind of the antithesis of the stuff that he thinks is exciting and promising. You see that when he talks about the cresting wave of the counterculture that it sort of peaks; it’s already in decline during the age of Nixon. It’s kind of a freewheeling epitaph for the 1960s, really.”

There’s a scene near the conclusion of the book where Thompson’s at a bar, trying to buy an ape — because, really, how else would this story end?

“You found the American dream?” the ape’s would-be seller asks him incredulously. “In this town?”

Of course he did; it had to be in Vegas. It had to be in a 24-hour city where possibility never sleeps, where the roulette never stops spinning, where that next big win is always around the corner — tantalizingly out of view, but most assuredly there, right?

OK, maybe we’re being a tad hyperbolic, a bit over the top.

But perhaps Thompson wrote it best, after his attorney tells him that he threatened to rip the lungs out of a taxi cab wrangler at McCarran.

“You can’t be subtle in this town.”

Contact Jason Bracelin at jbracelin@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0476. Follow @jbracelin76 on Instagram