Gatherer of the Iconoclasts

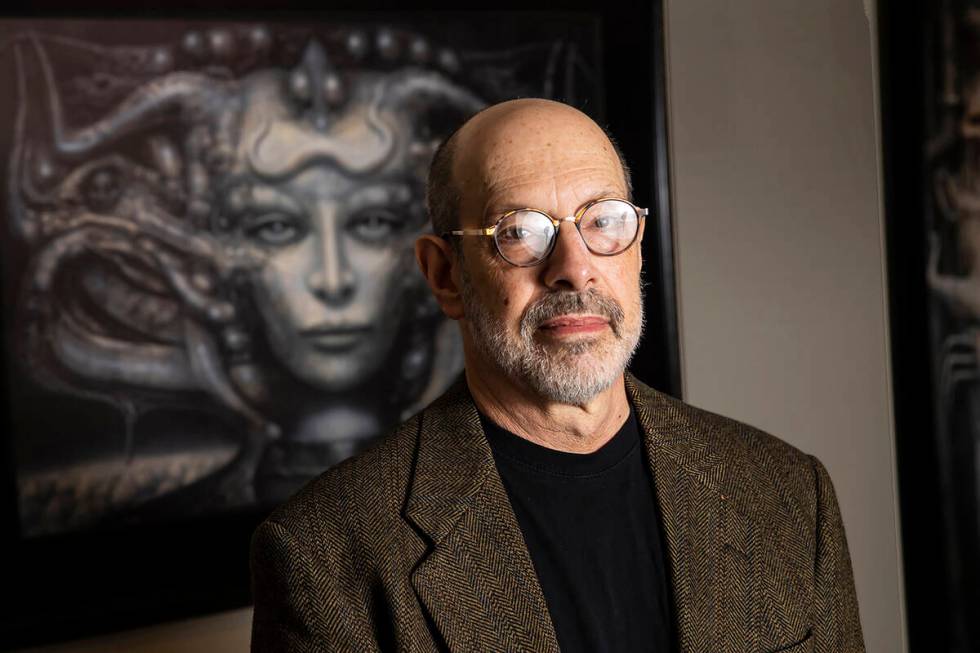

In the late 1980s, James Cowan put the equivalent of an average house on his credit cards for a venture he knew next to nothing about. At the time, Cowan, now a 20-year Las Vegas resident, was living in Los Angeles. He’d spent a decade trying to break into the movie industry, coming enticingly close to getting scripts produced before the projects were derailed.

Cowan, a long-time science fiction buff, had recently become obsessed with Ridley Scott’s Alien franchise. The dark sets, special effects and creatures in the movies were created by the Swiss surrealist painter Hans Ruedi (H.R.) Giger. Giger’s erotic, sometimes satanic, airbrush canvases pioneered a biomechanical style that incorporates machinery into human forms. Giger won an Oscar in 1980 for special effects on the first Alien film, but he was virtually unknown in the United States.

On a whim, Cowan, then in his mid-30s, called up Giger’s Swiss agent and asked how he could help. The agent told Cowan that if he could print Giger’s art books for distribution in the United States, he could sell the artist’s posters and prints in America. Cowan had no formal art education and no experience in book publishing or distribution. But he jumped in with both feet, loading $85,000 on his credit cards.

Learning as he went, Cowan secured a printer in Hong Kong, a U.S. distributor and brought Giger’s work to the attention of American audiences. The U.S. edition of Giger’s Alien was released in 1989 and sold out its printing of 10,000 copies within a year. Giger would remain an obscure artist despite rock musicians ranging from Blondie’s Debbie Harry to the Dead Kennedys using his work for their albums — sometimes to their detriment.

Cowan built on Alien to publish dozens of other books and calendars both with Giger’s art but also a growing stable of cutting-edge painters from around the world, including Zdzisław Beksiński, De Es Schwertberger, Alexander Mikhalchuk and Dariusz Zawadzki. He became the go-to person in the U.S. for modern surrealism and fantasy art, but he still remembers the terror of going heavily into credit card debt with a real chance of failure.

“I knew that was a major crossroads for me, and an opportunity to do something that I was actually passionate about,” he says. “So, I took the plunge.”

H.R. Giger and his fellow modern surrealists expose what they see as the irony and superficiality of the modern world. Their work often raises questions about the role of technology, which was supposed to create a panacea but instead has jeopardized privacy, autonomy and even democracy. Smartphones, social media and coming artificial intelligence may have put humans on a path to the dystopian world portrayed in Giger’s paintings. It’s notable that in Giger’s work, such as “Biomechanoiden” (1969), nonorganic materials take on semihuman qualities, and not always the best ones. Technology may seem inert, he seems to say, but it’s very much alive. The art also has a dreamlike quality that, despite some dark subject matter, finds beauty and imagination in visuals depicting things that cannot exist but appear surprisingly real.

Las Vegas, with its freewheeling reputation, libertarian ideals and over-the-top neon landscape, is the perfect place for Cowan to market the art that portends an uncertain future. “There’s a sense of acceptance and freedom in Nevada that I felt was leaking out of California,” Cowan says.

I’ve known Cowan for nearly a decade. We met when I was looking to add to my own Giger collection and having trouble finding anything available. Then I learned that Giger’s only U.S. publisher worked out of Las Vegas. I wrote to Cowan and soon began buying art from him. I even asked him to commission an original oil painting by Polish artist Dariusz Zawadzki. Later, when I realized that the Zawadzki piece had tripled in value, I asked Cowan to sell it for me for a commission. It remains on his website, unsold. For armchair collectors like me, the idea of selling art often sounds more profitable than the reality.

But Cowan is no armchair collector. He knows every brushstroke and contour — and he knows their worth. This knowledge, like all the best kinds of knowledge, has been hard earned through a history of bruised ego and blind alleys and, ultimately, discovery.

A streak of adventure and reinvention runs in Cowan’s family. His Brooklyn-born father completed his military service in Texas and then, rather than heading back east, took up rodeo and ranching. Before Cowan was born in Kansas City in 1951, his father was working as a cowboy, running herds of cattle for area ranchers. When Cowan was in his early teens, the family moved to Milwaukee.

Tall, fit and appearing a decade younger than his age, Cowan describes himself as a nerd before nerds became masters of the universe. An only child, he immersed himself in science fiction books, making models of airplanes and ships and watching old movies. He studied Russian history at the University of Wisconsin and was drawn to the country’s strange civil war filled with anarchists, Bolsheviks and Cossacks. “The Russian Civil War,” Cowan says, “is actually a surreal event.”

Between classes, Cowan started a literary magazine dedicated to science fiction, interviewing Carl Sagan, Harlan Ellison and Ray Bradbury. After graduating, he drove his four-cylinder Toyota from Wisconsin to Los Angeles. He knew no one in Hollywood but was thrilled to find an affordable apartment in the heart of the movie industry — until the first night.

“About three or four in the morning all of the hookers came (home),” he says. “It was basically a hooker place. It was really noisy and I lost my security deposit and moved and found another place that was a little quieter.”

Cowan stumbled upon a Salvador Dali lithograph at a local gallery and decided to buy it before even securing a job. “I bought it and put it on layaway,” he says of the print that still hangs in his office today, “which was profoundly irresponsible.”

Cowan soon found a sales job in Southern California and enrolled at Southwestern Law School. He hated it. At the end of his first year, he was at a film festival where he met a man wearing a University of Southern California cinema school shirt. Not realizing there was a film school, he asked the man about it and was soon enrolled at USC.

But again, he didn’t last long. A year in, Cowan was offered a job to work as an assistant to the head writer for a new sci-fi series on NBC, so he quit film school. Unfortunately, the network soon decided to replace all the science fiction aficionados with old TV hands. “So there I left school,” he says, “and that was my introduction to Hollywood: no job.”

To make ends meet, Cowan landed a job managing a staffing agency. Outside work, he practically lived at movie theaters, seeing, he estimates, 200 films a year. He was also writing screenplays and hoping a sale would get him back into entertainment.

Then he saw Alien. Banking that Giger’s popularity would increase with the success of the film franchise, Cowan decided to go deep in debt to finance the first U.S. printing of Giger’s Alien.

Giger’s work was controversial. One of his famous pictures, called “Satan 1,” ended up on the cover of Zurich thrash metal band Celtic Frost. It shows Satan using Jesus on the cross as a slingshot with snakes and demons around a landscape of dead bodies. When the Dead Kennedys included a poster of Giger’s painting called “Penis Landscape” with one of their records, the resulting obscenity trial nearly bankrupted the punk band’s record label.

For one of Cowan’s next books, Necronomicon, the distributor was concerned about the explicit sexual content on the cover, so Cowan placed stickers on the shrink wrap to cover the offending portions. The stickers served double duty, satisfying the distributors while touting Giger’s connection to the Alien movies.

Cowan isn’t sure whether the dark subject matter, Giger’s European home base or just Americans’ preoccupation with trivial art kept Giger from widespread fame. “You have to be a little bit more suspicious and leery of the people that are painting puppies and flowers and butterflies than the ones that are doing the dark, disturbing imagery,” he says.

“I think they kind of get all that angst out of their system through their artwork.”

Along with his art business, Cowan found writing partners for his screenplay ambitions. One such project was an adaptation of The Jungle, Upton Sinclair’s unflinching 1906 depiction of the meatpacking industry, but no production deal materialized.

In the late ’90s, Cowan had a couple of screenplays in development with Fox and a Saturday morning kids’ series for the Fox Kids network that he says had a $2 million toy deal attached. But Fox Kids was sold and the movie division closed down. Cowan lost his agent. “Everything blew up and it blew up not in a good way,” he says. “I had been trying to break into the Hollywood scene as a writer for 20 years, so it’s 20 years of work, you know, up in smoke.”

For Cowan, promoting obscure art was proving to be more profitable than writing for Hollywood. He started researching other artists — mostly overseas surrealists with no platform in the United States. Cowan dismisses modern blockbuster artists like Jean-Michel Basquiat, whose work garners megamillions at auction. Blockbuster status, he says, is often more about the promotion than the art. Hollywood has taught him well.

“The art world is a very fickle place,” he says. “It’s not a merit-based system. It’s a marketing-based system and an influence-based system. … There’s a certain amount of manipulation going on.”

Cowan looks for specific talents and skills in the artists he represents. “A lot of people can paint technically well but they don’t have any ideas,” he says. “And a lot of people may have some ideas, but they don’t know how to paint. So to find someone who is elite in both of those capacities is a rare thing.”

In 1995, he opened a gallery in Beverly Hills, but people often showed up more to drink the free wine than to buy art. He found most of his business was being done online so there was no reason to have a physical location.

In 2003, when Cowan moved to Las Vegas for its more affordable housing, he decided to focus on his artists. While continuing to run his website for Giger and similar artists, he started placing works in galleries around the Strip such as Jack Galleries and Art Encounter. He also hosted pop-up events and showed his artists at conventions. Soon he was making enough of a name in the surrealist community that artists were seeking him out. He helped foster the careers of such unique talents as Jota Leal, a Venezuelan painter who paints surrealist pictures of famous actors and movie characters from the 1950s to the 1990s, and Geoffrey Gersten, who paints robots and video game and cartoon characters in incongruous settings, like on a basketball court or battlefield.

Gersten says that a chance meeting with Cowan at a World of Art Showcase at the Wynn in 2012 led to him making his living as an artist. As Gersten was unpacking and setting up for the show, Leal pointed out Gersten’s work to Cowan, who put his glasses on and got within inches of the canvas, inspecting every detail.

“I didn’t know anything about art (at the time), but I knew how it made me feel,” says Gersten, whose studio is in Scottsdale, Arizona. “He made the work available to the public on his platform.”

For Cowan, the collection and promotion of unique, challenging, even disturbing art has provided a living and a place in the world. It’s an irony that these dark and sublime abstractions brought solidity to Cowan’s working life. Today, he considers himself semiretired but has more projects going than the average Type A in midcareer. He still sells art from his website, MorpheusGallery.com. He is producing a line of wristwatches. And despite his Hollywood woes, he continues to write scripts with an old buddy he met while running his Beverly Hills gallery.

In about 2001, Cowan and his writing partner, Aaron Mason, finished a script about a German tank crew stuck behind enemy lines — a project that united Cowan’s love of Russian history, supernatural monsters and surreal environments. So far, there have been close calls, but no production deal.

“We never dropped (the idea),” Mason says. “We kept the flame burning. It’s changed, and there’s been a long gestation period, but … it’s very much alive.” ◆