The Road to Ali: In the footsteps of a legend’s legacy

City driving is an exercise in boredom, danger and anger. We stop, we go, we turn and turn again, a short stretch of speed, stop again, look at that idiot who doesn’t use a blinker and ought to have his license revoked, same with the texting jerk who just cut me off. Jack Kerouac, this is not. Driving across America, however, is a more delightful matter altogether, a paradoxical high-speed rebellion against the pace of American life — the practice of patience at 70 miles per hour. I’m not looking for some big breakthrough on the road, just the chance to see with my eyes, feel my body behind the wheel, listen to the chapters of a good book, catch the ambiguous sensation of a slow and ageless landmass and a country swiftly passing me by. As rebellions go, it’s low-cost, high-yield, and in my case, as I set off across the desert and beyond, it fits the purpose of this pilgrimage across flats and peaks, long stretches of high-grass prairie, through forests and then hilly southern Indiana and finally to the Muhammad Ali Center in Louisville, Kentucky. I’m off to commune with the hero of my youth, the avatar of flow and grace and brutality, The Greatest himself, Muhammad Ali.

I’ve got a lot of miles ahead of me, but I don’t like flying. And this legend is worth the drive, the time to think: a man who left a meaningful legacy for the ring, the world, and the city of Las Vegas. He lives on with particular vividness for those of us who lived through the clamorous ’60s, the glam and bewildered ’70s, and the ’80s, when our hero grew suddenly old in the ring and my generation’s revolutionary energy finally gave out.

Las Vegas is in my rearview now; I am heading south, taking the long, long road through Flagstaff, Arizona, then New Mexico and Texas. But the lights behind me are telling me stories about Ali near the end, when a great career ended but a desert boxing capital of the world was born.

Ali’s first fight in Las Vegas was a 10-round decision over Duke Sabedong on June 26, 1961. It was his first professional fight to take place neither in his hometown of Louisville nor his training headquarters of Miami. He’d won the Olympic gold medal in Rome in 1960 and arrived in Las Vegas a hot 6-0, with quick hands, a mouth to match, and plenty of doubters that a heavyweight could be both pretty and brutal. The next time he fought in Las Vegas, he was 21-0 and the Heavyweight Champion of the World.

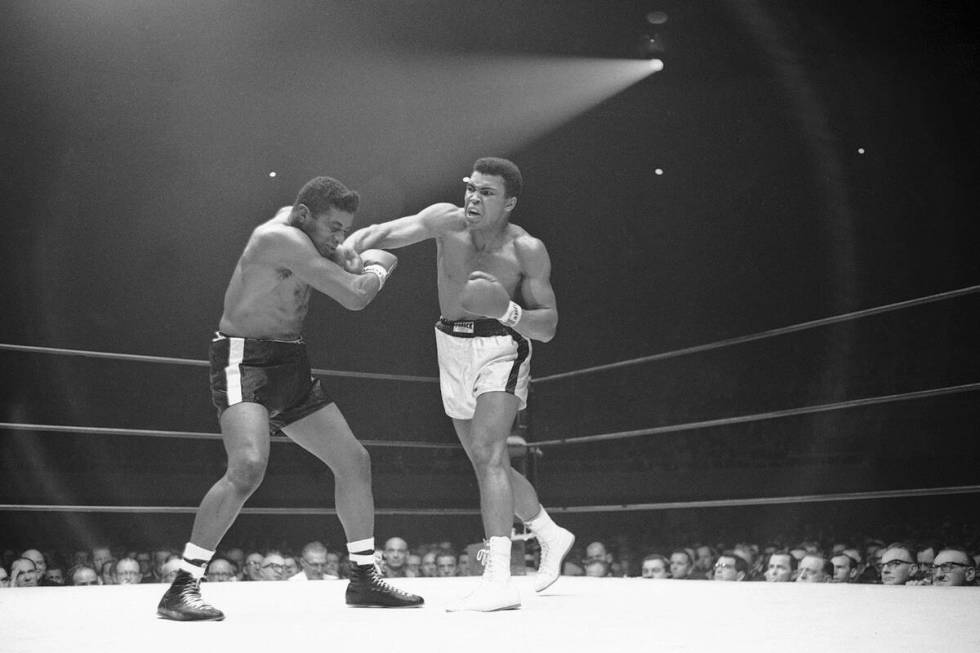

On November 22, 1965, Ali took on Floyd Patterson at the Las Vegas Convention Center. The fight was two years to the day from the assassination of John F. Kennedy; it was taking place not only in a changing city, but in a swiftly changing America, one in which a Louisville kid named Cassius Clay had 18 months earlier crushed the heavily favored Sonny Liston and taken his championship belt, then promptly announced that he’d joined the Nation of Islam and changed his name to Muhammad Ali. In a just a few moves, Clay had gone from an underrated pretty face with quick hands, quick wit, and and a gold medal from the 1960 Olympic games to a brutal fighting machine and bona fide American rebel villain. In the run-up to the fight, Patterson said Ali had been misled into joining the Nation of Islam and insisted on continuing to call him Clay. This was fuel for the young champ, who hammered and stung and dissected Patterson for 12 rounds of a technical knockout, mocking him all the while as an Uncle Tom. “Come on, white American,” Ali said to Patterson, who was Black, “Come on!” Another punch. And another.

High desert, scrubby cacti, red-tipped ocotillo. Small, odd, lonely houses sitting isolated, as if unconcerned by the amenities and securities we moderns require — hospitals, pharmacies, corner markets, payday loan shops. Who lives in these outposts, these little revolts against the logic of the urban? If one looks left or right, the landscape is captured in a flash, as if from the eyes of a swift animal scanning the surroundings in search of predators. Looking forward, the horizon opens up in the distance and the world is seen in another way, wide and slow like staring at a landscape painting from a Dutch master, but with the floor moving quickly underneath like an out-of-control treadmill. This is not urban time, but highway time and space, at once fast and slow. At last the landscape changes, and I’m deep into Interstate 40, just a few dozen miles from Flagstaff. I begin to roll alongside the BNSF Railway — formerly the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe, of Judy Garland fame — pulling mostly long lines of boxcars through eastern Arizona, out to Albuquerque, across northern Texas before taking a turn toward Chicago, almost my precise directions.

At the peak of a mountain pass I hit a fierce thunderstorm and drop from 75 down to 20 as lightning flares all around. I founder through the water wake of an 18-wheeler that moves along grudgingly, sullenly. Passing a truck like this in a bad storm is like inching through a car wash with the wall moving closer on the right, except in this instance my small station wagon is lifting off the ground. If the lightning comes close, I think, it’s going to strike that big truck with the metal sheath. These trucks and their drivers don’t give up their share of the road easily. I saw the aftermath of three encounters between a car and a big rig, with the smaller of the two always on the bad end of the deal.

Soon I am heading into eastern New Mexico. It is the kind of West that puts one in mind of the movies, but the movies, of course, had it all wrong. The great Hollywood story about the West, where Europeans were turned into Americans by access to a homestead, easy freedom, and a short, sharp, and ugly victory over native peoples — that story had been transformed by the labor of historians. The land I am driving through is a fractured geographical area, where in Colorado, Arizona and Nevada mine workers violently battled mine owners after the romance of panning for gold nuggets shifted in the “mineral west” to corporate mines with absentee owners, mining engineers, shafts, tunnels, tracks, cages 2,000 feet below ground, hoists and blasting equipment. The ground, the water on and in it, the cattle, the new towns, the politics — all of it was a dramatically contested business. The railroad business too, despite the nostalgic image one can conjure up, was hardly the refuge from industrialism.

For me, growing up in the working-class-and-federal-prison coastal California town of Lompoc, the son of a charismatic alcoholic devoted union laborer and an iron-willed former professional baseball player, Ali was part of an emerging consciousness in a world where the game was unfair but the fight for something better — we didn’t know what to call it but some nebulous variant of the much-abused word “freedom” — was deliciously enticing. My four brothers and I grew up fierce, mischievous, relentless. Our front-yard basketball hoop was the local all-comers battleground, the place where the boys of our town became the best of enemies and the most ruthless of friends. We were lovers of sport, of confrontation, of the burial of dead rules and the rise of rock ’n’ roll. Of course, if we ever got out of line, my mom, Helen Callaghan, slight and often saddened by her own confrontations with a hard life, struggled to be the toughest of us all. She was the ballplayer, by the way, a pioneer of the World War II-era All-American Girls Professional Baseball League, later made famous by the film A League of Their Own, which was based on a documentary film of the same name that my twin brother made. So, yes, we were born with some fight in us.

In April 1967, when I was 13, the United States government made Muhammad Ali my hero. Or to put in the affirmative, Ali made himself a hero by refusing to be drafted into the Army. He refused to step forward, to move, when his name was called out in the Houston examination office, a step that would have him join a fighting force carrying out nearly unprecedented violence in the bloody quagmire of Vietnam.

Ali’s title was taken from him, and for 3½ years he could not fight in the ring. He knew in his bones that this battle could not be won, but he told the country that his real enemy was here in the United States, those who attacked black people with fire hoses and dogs on the streets of Birmingham:

“Why should they ask me to put on a uniform and go 10,000 miles from home and drop bombs and bullets on brown people in Vietnam while so-called Negro people in Louisville are treated like dogs and denied simple human rights? No, I’m not going 10,000 miles from home to help murder and burn another poor nation simply to continue the domination of white slave masters of the darker people the world over. This is the day when such evils must come to an end. I have been warned that to take such a stand would cost me millions of dollars. But I have said it once and I will say it again: The real enemy of my people is here. I will not disgrace my religion, my people or myself by becoming a tool to enslave those who are fighting for their own justice, freedom and equality. … If I thought the war was going to bring freedom and equality to 22 million of my people, they wouldn’t have to draft me, I’d join tomorrow. I have nothing to lose by standing up for my beliefs. So I’ll go to jail, so what? We’ve been in jail for 400 years.”

A fighter who wouldn’t fight? Millions of white Americans hated the man. My brothers and I loved him.

Ali returned to the ring in 1970 with a three-round TKO of Jerry Quarry. A year later, he got his title shot against the new champ, Joe Frazier, in New York City but lost in a 15-round decision. Later in 1971, he captured the North American Boxing Federation heavyweight title with a win over Jimmy Ellis. On June 27, 1972, he returned to Las Vegas to defend his NABF title against Quarry. Ali was once again the King of Vegas, knocking out Quarry in seven rounds. Six months later, on Valentine’s Day 1973, Ali was again in Las Vegas, showing no love to Joe Bugner, who valiantly went the distance in defeat and inspired the creation of a character named Rocky Balboa who, as crazy as it sounds, eventually transforms himself into an Ali-like boxer. Before Ali’s next Las Vegas bout on May 16, 1975, he predicted an eighth-round knockout of Ron Lyle but had to settle for an 11-round TKO at the Convention Center. Ali’s fights during this period tended to last; there was an epic quality even to the lesser bouts. The fights gave room for stories to be told.

It was an age of giants in the heavyweight ranks — Joe Frazier, Ken Norton and George Foreman were all battling at the same time, walking the path Ali had helped clear for them to global fame and extraordinary fortune. Ali was stalking the world title, the one that had been taken away not in the ring but in the boardroom. None of Ali’s legendary fights against that trio took place in Las Vegas —Ali knocked out Foreman in Zaire in eight rounds ’74; in ’75 he TKO’d Frazier in 14 rounds in the Philippines. (The Norton fights in 1973 — first a loss for Ali, then a win — took place in less exotic Southern California.) But the fact that Ali, the giant among giants, had made Las Vegas one of his boxing homes helped put the city on the global sports map.

In many ways, Ali fused with the aesthetic of the Vegas ’70s — showmanship, excess, outlandishness, a dollop of kitsch. It was the Las Vegas of Liberace and Wayne Newton in all his crooning glory. It was, above all, for a few years before the excess became too excessive and tragedy struck, the Las Vegas of Elvis. Elvis loved Ali, and Ali loved Elvis. The singer considered Ali the Elvis of boxing, and the boxer considered Elvis the Ali of music. Both of them had reinvented their arts and built the tallest platforms in the world, dressing themselves in swagger and making themselves open targets as they bobbed and weaved and changed in ways that were not always to everyone’s liking. Elvis had been an earlier hero of mine, but had lost me by this time: Blue Hawaii and sequins had somehow overflowed the memory of Jailhouse Rock. But Ali was astute in seeing that even Vegas Elvis was an American original, a rebel, a man unwilling to compromise even when they told him he’d become a parody of himself. They met in Las Vegas in 1973. Ali gave Elvis a pair of boxing gloves on which he wrote that Elvis was the greatest. Elvis gave Ali a sequined boxing robe. Ali wore it once, and lost.

An 18-wheeler, mistaking itself for a roadster, passes me on the right. The 18-wheeler is the enemy of the casual driver just wanting to make it across the country alive. But if I am brutally honest with myself — and why shouldn’t I be, out here alone? — the 18-wheelers are the essence of the road, one of the reasons for the existence of the interstate highway system. Their job is to turn products into money by way of diesel power. When was the last time I ate something that did not, in some way, arrive by a truck? I dream that everything I need comes on my beloved trains, but that’s just a dream. None of this makes me like 18-wheelers any better as they pull out surprisingly to pass another, slower, hauler of toys, or neckties, or frozen steaks, to a warehouse in Memphis or Chicago or Philadelphia.

I am in Texas, which is followed by more Texas, which is followed by still more Texas. Why am I out here? Am I doing it for my rebel hero? How deep is my devotion, how deeply can a son of a churchless home be devoted? Very, as it turns out. In north Texas, a massive cross dwarfs a small church. Are the voices rising with the light? Do they have a prayer for the rebels of this world, the ones who did not win their fame, or maybe even their freedom? What becomes of the meek who tire of meekness? Do they become champions of the world? Or do they simply dream, a powerful thing in itself?

On February 15, 1978, Ali took on 1976 Olympic gold medal winner Leon Spinks at the Las Vegas Hilton. After 15 rounds Spinks emerged, shockingly, the winner and inheritor of Ali’s World Boxing Association heavyweight crown. That fight was a tragedy that I cannot bear to watch ever again, no matter how much YouTube suggests it to me.

The other story, if we want to put a positive spin on that bleak day, was that the spectacle of The Greatest fighting at the Hilton helped establish casino properties as not only plausible but preeminent sites for major title bouts. (Ali’s previous Las Vegas fights had been at the Convention Center.) Though the sold-out venue held only 5,300 seats, it paved the way for the megafights of the 1980s featuring such stars as Sugar Ray Leonard, Thomas Hearns, Marvin Hagler and Roberto Duran, not to mention 1990s bouts featuring the likes of Mike Tyson, Evander Holyfield, and that piece of Holyfield’s ear.

Later in 1978, Ali would avenge the loss and retake his title, wringing out Spinks in 15 rounds before more than 63,000 fans in the New Orleans Superdome. The massive crowd was a sign that Las Vegas needed bigger, grander venues. So when Ali returned to fight in Las Vegas one last time on October 2, 1980, Caesars Palace constructed a 24,800-seat temporary venue in the parking lot, an enduring strategy in the years before Las Vegas became home to massive arenas on every block. The fight was a sad epitaph to Ali’s brilliant career, as Holmes defeated a cliché, a man playing at being the fierce boxer of old, a self-parody of the nimble “dancing Ali” (“the old Ali is back,” a ringside commentator said hopefully, foolishly). With Ali, self-deception and foolish hope was easy. He knew we wanted something important from him, something to satisfy our need to escape boredom, to ally with someone with deep commitments, someone going places, a person who would sacrifice himself for our pleasure, our well-being. Ali could sometimes score points simply by presenting a younger Ali, his own heroic self-image as seen in the eyes of others. But not that night. Larry Holmes did this deeply admired man a favor by not knocking his brains around inside his skull. He could have, but he didn’t. Holmes later said, “I’m prouder of sparring with him when he was young than I am of beating him when he is old.”

Do we grow from defeat, get stronger because of it? Ali often seemed to. Losing to Frazier in their first fight, toughened him in the ring. Losing — at least on the surface — to the U.S. government toughened him in his convictions. But defeat can also just make us weak. It can even destroy us.

Ali could have died in the ring on that October night in 1980 against Holmes. Ferdie Pacheco, Ali’s physician, thought so and said so. That philosophical nostrum “that which does not destroy me makes me stronger” is nonsense. Near-destruction changes us. Ali should have known, but the king is the last to see the chinks in the armor. Maybe the payday and pageantry blinded him — and us, too. The great man, we thought, would always be great in the ways that mattered, in the ring.

Ali fought only one more time, losing to Trevor Berbick in 10 rounds in the Bahamas on December 11, 1981. Some can bear their sorrows and afflictions better than others. They have resources others don’t have. Ali was that type, born to bear afflictions. And his resources were many. His commitment to his religion, to his god, provided him solace and emotional stability long before his hands began to tremble.

Onward I roll, through the red-soil Choctaw country of southeastern Oklahoma, onward to Oklahoma City and then to Tulsa, where I pay my respects to another of my cultural heroes at the Bob Dylan Museum. Dylan, by the way, was an admirer of Ali, though he sang playfully of getting in the ring with him in his “I Shall Be Free No. 10” on the 1964 album Another Side of Bob Dylan. I checked out Dylan’s notebooks, photographed the guitar from Blood on the Tracks, reflected on Dylan’s words when Ali died in 2016: “If the measure of greatness is to gladden the heart of every human being on the face of the earth, then he truly was the greatest.” Two men, born eight months apart, both bound to challenge and confound and, to the extent the musicians and boxers can do such a thing, change the world. I get back on the road, taking my time, rolling across Missouri and Illinois, past New Harmony, Indiana, where a utopian socialist colony rose in 1825 and fell in 1827. This is the pathos of dreams. They rise, they fall. Some leave a trace; most do not. Suddenly I realize that the time will change when I reach the Kentucky border, and that I might not reach my destination before closing time. So I drive hard, and illegally. And I make it.

The Ali Center sits along the Ohio River in Louisville, not far from the baseball bat factory where another kind of slugger is made. For those familiar with similar places — Jefferson’s Monticello, the Elvis Museum in Memphis, Liberace’s defunct place in Las Vegas — a lot of what is expected is on offer. The photos and words and old boxing trunks in big plastic cases, boxing footage projected on a canvas ring, the awards, the testimonials from friends and family and opponents. There is a familiar storyline, something of a black Horatio Alger: Cassius Clay struggling against all odds, Louisville poor and understanding prejudice, overcoming it, meeting a police sergeant named Joe Martin who teaches him a thing or two about the ring. Then the bootstraps, the success, the revelation that brings transformation into a new being, from Clay to Ali. The continuing struggle against great odds and the great power of his own government, then success again, growth, enlightenment. A changing man meets a changing world and the rebel becomes an example to us all. He lights a torch. He dies loved by the world. I know the story, its ending, its message. I’m just happy to be here, to revisit and revise my understanding of the object that is Ali. I might not get another chance to pay homage to a man who taught me a thing or two about having to get up after being knocked to the ground.

Of course, his beautiful athletic physicality is on display, his impossible and dangerous measuring of the minute space between a man’s fast-moving fist and his face. Of course, his brilliant lines of attack and evasion were on display in the footage, against Cleveland “Cat” Williams, against Ernie Shavers, against Henry Cooper. But also on display, the Center’s credit, is his deep attachment until the mid-1970s to the Nation of Islam and its hard-line separatist leaders, whose ardor often bordered on gangsterism. And so too are interviews where Ali, early on, denigrates other religions, subjects women to ugly crudities and stereotypes, his refusing to let his first wife speak in front of the cameras. We get a glimpse of an Ali who was no ideological friend to liberal sensibilities of the time. Ali left the Nation of Islam in 1975 for mainstream Islam; at the end of the video, Billy Crystal appears to tell us the obvious: Ali changed over time; he became more tolerant, more open to the world and its complexities, interested in the spiritual needs of others, a man more generous in his embrace of the flawed and ugly and beautiful human tapestry around him.

So the pulverized veins, the crushed eye sockets, the blood-covered trunks, the whole ruthless business that is boxing is placed side by side with the wistful affection that nostalgia brings. First, the footage, after Ali knocked the hell out of Chuck Wepner for 15 rounds, of the vanquished opponent dragged back to his corner, as one ringside commentator put it, like a dead bull. Then images of Ali in motion, the “poetic” boxer, the only fighter whom intellectuals like Norman Mailer could love. How elegant was his calculating violent beautiful brutality! Yes, we loved it.

That’s the trick, the magic of Muhammad Ali. Even students of all things refined, prone to disdain aggression, loved Ali’s fierce and distinctive gladiatorial violence, the subtlety of it. The style and bravado brought us into Ali’s tent, where death-defying feats would be mastered, miracles performed before your very eyes. He beat the U.S. government, didn’t he? Of course he would beat George Foreman in Zaire, that rumble in Kinshasa, where he was only a 4-1 underdog — he’d been an 8-1 underdog against Sonny Liston the first time around.

When everything in the world seemed horrible — the Vietnam War, assassinations of political leaders across the globe, black Americans beaten in the streets for demanding equal rights — when a generation of young men and women considered their odds of a decent life in a decent society at 4-1, Ali was a delightful and forceful tonic, idiosyncratic, boisterous, comic, deeply serious, original in 121 ways. After the initial carnival barking routine he learned from the “professional wrestler” Gorgeous George, Muhammed Ali got down to the thing that was essential to his success: discipline. He ran the miles, skipped the rope, worked the speed bag, sparred the rounds, shaped the body and the body’s senses better and more vigorously than his challengers. Ali did not place himself counter to the culture of his time that in theory respected hard work and self-discipline. Ali admired upward mobility — his own, most importantly — and, while he was renowned for rejecting authority, he respected it when he considered it to be justifiably earned, in the ring or on social and political battlefields everywhere. Ali earned his authority. As I walk the halls of the Ali Center, pausing at exhibits, watching him on film, alive in the ring once more, I can think for a moment, absurdly, that, no, it wasn’t Johnson or Nixon or Kissinger calling the shots during the “years of hope, the days of rage” that were the 1960s and 1970s. It was Muhammad Ali. ◆