Those who knew him best still say Sonny Liston was done in

The milk bottles were still full, the newspapers unread. They cluttered the doorstep outside the house on Ottawa Drive, and Geraldine Liston was puzzled by the sight.

Returning to Las Vegas from St. Louis on the night of Jan. 5, 1971, after spending Christmas with her mother, Geraldine became suspicious. Her husband had been out of contact for 12 days, but his black Cadillac was in the carport. Where could he have run to? The Westside? Los Angeles?

The front door was unlocked, and several of the windows were open. But even the cool January air couldn’t mask the odor of rotting flesh.

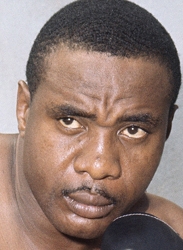

In the main bedroom, Geraldine discovered the body of her husband, former heavyweight champion Charles "Sonny" Liston. He had been dead several days.

Liston’s death four decades ago was quickly called a possible heroin overdose, although those who knew him swore he was afraid of needles and wouldn’t touch the stuff. Authorities discovered a balloon of heroin in the kitchen and a needle mark on his arm, but no syringe. The Clark County coroner found traces of morphine in his system, but not enough to conclusively determine it was the cause of death. It was decided that the death of the man who once was the most feared heavyweight in the world was probably a result of a heart attack and congestive lung failure.

His age was listed at 38, but boxing insiders say he could have been several years older. The 24th of 25 children born to an abusive Arkansas sharecropper, Liston didn’t know the exact date of his birth.

Skeptics of the police and the Vegas game suspected Liston’s old mob connections had finally caught up with him. He’d also been collecting for a local loan shark and by night was running on the Westside with a crew of heroin dealers. By day he struggled to keep his fading boxing career afloat after the vicious beating of Chuck Wepner on June 29, 1970, at the Armory in Jersey City, N.J. Known as "the Bayonne Bleeder," Wepner left the ring needing 57 stitches to close his wounds. At the time of his death, Liston was negotiating for a fight against Canadian heavyweight George Chuvalo.

Liston was running out of options when he ran out of time, but he still had some friends. Lem Banker was one.

"Sonny could be a real good guy," Banker says.

At Christmas, Banker and Liston exchanged gifts. Sonny gave Lem a personal recording of a song. Lem gave Sonny an expensive watch.

A day or so later, Liston called his pal and sparring partner Gary Bates.

"The night he died, I went over there to his house on Ottawa with a cocktail waitress from Circus Circus," the former professional boxer recalls. "Sonny had called and said Geraldine was gone for the holiday, and why don’t I come over. I knocked on the door a couple times, but nobody answered. Nobody showed up. Later I read in the paper that he’d passed away."

Liston and Bates chased women and good times together.

"I loved Sonny Liston," Bates says. "And to spar with him was terrifying. I figured every time I went down there, I was about to become a martyr. I thought it was my last day on Earth."

Like many Las Vegans, Bates heard street talk about Liston’s death, whispers that stretched into the dark heart of the town.

"There were rumors he was collecting for a shylock in town and had drawn the wrath by bringing too much attention to himself," Bates says.

Banker also suspects he was murdered: "He had some needle marks on him, but he would never take a needle as far as I know."

Banker was at the Wepner fight, for which Liston was paid just $13,000. That didn’t cover Liston’s debts and expenses. He was broke again, forced once more to earn a living with his hands outside the ring.

"Today, he’d have gotten $30 million for that fight," Banker says.

When Liston returned home, Banker received a call from Sheriff Ralph Lamb, who had a message for the former champ: Stay away from the drug dealers on the Westside. Banker says he delivered the message.

Did Liston fail to listen?

As a regular at Johnny Tocco’s Ringside Gym downtown, I became well-acquainted with Liston’s ghost. The Ringside was Liston’s last training sweatshop, and Johnny was a keeper of Sonny’s story and was his trainer for the Wepner fight.

The world loved to hate Liston, but Johnny loved the man. He often told the story of seeing the scars on Liston’s back and the fighter’s response to the trainer’s curious inquiry: "I had bad dealings with my daddy."

For years whenever Liston’s name entered the conversation down at the gym, Tocco would say with the certainty of a connected guy that despite what the local cops claimed, Sonny was done in by the mob.

Some time later, after a story about Liston quoted Tocco’s statement and made a national splash, Johnny suddenly changed his tune.

Maybe it was an accident after all, Tocco said.

At least publicly, Geraldine Liston never bought into the overdose theory.

"If he was killed, I don’t know who would do it," she told Sports Illustrated’s William Nack. "If he was doing drugs, he didn’t act like he was drugged. Sonny wasn’t on dope. He had high blood pressure, and he had been out drinking in late December. As far as I’m concerned, he had a heart attack. Case closed."

The late Harold Conrad promoted several Liston fights and knew the heavyweight well. He believed Liston was murdered, probably with a hot shot by some of his fast company.

Liston had been raised in poverty with an abusive father, had been arrested two dozen times and served multiple stints in prison, had been the mob’s fiercest fighter, but in the end was expendable. In his memoir, "Dear Muffo," Conrad wrote, "I think he died the day he was born."

That sounds about right.

Four decades later, Charles "Sonny" Liston rests in Paradise Memorial Gardens. Jets full of Las Vegas visitors fly overhead and land at nearby McCarran International Airport.

His headstone reads, "A Man."

John L. Smith’s column appears Sunday, Tuesday, Wednesday and Friday. E-mail him at Smith@reviewjournal.com or call (702) 383-0295. He also blogs at lvrj.com/blogs/smith.