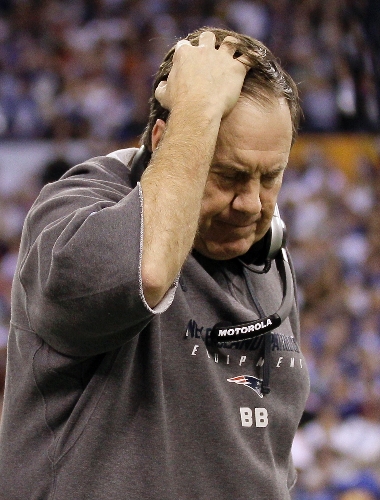

Belichick’s tactic passes strategic muster

INDIANAPOLIS — Bill Belichick gave clear instructions to his defensive unit: Let the runner score.

Playing the odds and inviting critics, the calculating coach of the New England Patriots told his players to get out of the way, open a wide path for Ahmad Bradshaw and give Tom Brady a chance to win the Super Bowl in the final 57 seconds.

Unusual? Certainly.

Crazy? Not at all.

The strategy failed, and the New York Giants won 21-17 on Sunday. But Belichick was certain it gave the Patriots their best opportunity.

They led 17-15 with 1:04 left but had only one timeout as New York faced a second down 6 yards from the goal line.

If the Patriots tackled Bradshaw, the clock would keep running if they didn’t use the timeout. If they did use it, the Giants could let the clock run after the next play, leaving precious few seconds with Lawrence Tynes setting up for a chip-shot field goal.

A field goal, Belichick said Monday, that had a “well over 90 percent success rate” from that distance.

And that strategy was used, although it also failed, in the 1998 Super Bowl by Green Bay Packers coach Mike Holmgren against the Denver Broncos.

Still, it went against the competitive nature of defensive players, whose job it is to keep opponents out of the end zone, and runners, whose goal it is to get there.

“It killed me,” said linebacker Brandon Spikes, a hard-hitting linebacker who simply stepped aside. “When the call came in to let them score, I was kind of like, ‘What? I’m here to do my job and it’s my job to play defense and let them score?’ It definitely was tough.”

Bradshaw also had to fight off his instincts. As he approached the goal line, he tried to stop, like someone trying to avoid losing his balance. But his momentum carried him across the goal line, falling backward, even as quarterback Eli Manning yelled at him to go down.

“I tried,” Bradshaw said, “but I couldn’t do it.”

So it was 21-17, and Brady had those 57 seconds to score a touchdown. He had done it many times before.

Starting at his 20-yard line, he threw two incompletions and then was sacked. But on fourth down, he connected with Deion Branch for 19 yards and a first down at the 33. Then he hooked up with Aaron Hernandez for 11 yards to the 44 before spiking the ball. The Giants then drew a 5-yard penalty, moving the ball to the Patriots 49.

Still a chance, however slim.

With nine seconds left, Brady threw an incompletion to Branch.

With five seconds left, there was only one option — a desperation pass into a crowd in the end zone. It got there but, with tight ends Hernandez and Rob Gronkowski nearby, it dropped to the ground, and the Patriots’ championship chances — and the clock — fell to zero.

Belichick’s strategy, sound though it might have been, didn’t work out.

“He made a good decision,” Brady said. “We left ourselves with a little bit of time.”

Belichick’s clear-the-way order was similar to Holmgren’s decision in the 1998 Super Bowl. The score was tied at 24 when he let Terrell Davis score on a 1-yard run with 1:45 left rather than allow the Broncos to run down the clock for a short field-goal attempt.

Brett Favre then led the Packers from their 30 to the Broncos 31. But after three straight incompletions, Denver regained possession with 28 seconds remaining, and John Elway kneeled down to end the game.

On Sunday, at least one person with a rooting interest, Giants running back Brandon Jacobs, knew Belichick’s gambit wouldn’t work.

“I respect Tom Brady and the New England Patriots,” Jacobs said. “He does a great job with the guys he has. But if that was Drew Brees or Aaron Rodgers on the other side, with those big-play outfits, 57 seconds would have been plenty enough time for those guys.”

The Patriots’ passes, he said, are much shorter.

“They needed a helluva lot more than 57 seconds to be able to win the football game,” Jacobs said. “So I wasn’t worried at all.”