Nevada’s native son: Corbett represents tribe at Super Bowl

SCHURZ

Everett Kinerson sauntered through the Walker River Paiute Tribe’s headquarters Wednesday afternoon with a navy blue Rams cap resting comfortably atop his head.

His sister ordered it for him. Probably on the internet. He wears it with pride, knowing his loyalties still lie with the big, jovial kid who would visit from Sparks on Thanksgiving or Christmas and the NFL team he represents. He can’t recall the last time he saw Austin Corbett, but knows he’ll see him again Sunday afternoon.

On his television screen — playing in Super Bowl LVI.

“There’s a lot of pride in that. Right here. From everyone. All of Indian country,” said Kinerson, Corbett’s great uncle who has lived on the reservation since 2004. “Everybody just feels great about the whole deal. We like to watch him play. They’re glad that he’s from here and that he’s a member here.”

Corbett, 26, is the lone Nevadan in Super Bowl LVI and a proud representative of Sparks, Reed High School, UNR — and the Walker River Paiute Tribe.

As a former Wolf Pack walk-on who was traded midway through his second NFL season by the team that chose him with the No. 33 pick in the 2018 draft, his resolve mirrors that of the 900 or so who make their life on the reservation, tucked away one of Northern Nevada’s barren crannies.

Naturally, his success is a source of pride in the Reno area, in Schurz and across the country among Native Americans, who share their enthusiastic support for Corbett on Facebook and in publications that cover their respective communities.

They’ll watch at 3:30 p.m. on Sunday, knowing “he’s representing Indian country. All over the country. … Every Indian newspaper, there’s a story about Austin. He’s everywhere,” said Evelda Martinez, a lifelong Schurz resident and one of Corbett’s distant cousins.

“This is home. It’s just a small reservation town. But when there’s something like that, something good happening with somebody, one of our people — people know everybody.”

Pride of the Paiute

The Walker River Paiute Tribe’s reservation was established in 1874 and sits about 90 miles southeast of Reno. Corbett never lived on the reservation, growing up instead in Sparks alongside other brother Garrett and younger sister Krystina. But his family would occasionally visit Schurz, from which his father Theron’s family descends.

Once or twice a year, Corbett, his parents and siblings would meander from the city center though the desolate desert toward Schurz.

The town is constructed around a few central streets, and houses are spaced along either side amidst the sand, rock and rubble that define the desert. Tribal burial grounds preserve the Walker River Paiute Tribe’s rich history, forming a conduit that connects past to the present. Mountains line the horizon.

Many of Corbett’s distant relatives — like Kinerson and Martinez — still live on the reservation, forming an inherently collaborative community where points of communal interest are all within walking distance and everybody seemingly knows everybody else.

Athletes like Corbett are celebrated, but so too are the college graduates who hail from Schurz and whose portraits hang from the wall in the lobby of the tribal headquarters. Resilience defines the reservation, per Amber Torres, the tribe’s chairwoman and a longtime football fan who cheered for the Rams well before Corbett wore their jersey.

“Anything that we do, we are always community,” said Torres. “We always try to empower our own tribal citizens, as well as any relative that we have that’s out there doing big things.”

Football is popular in Schurz and so too is Corbett, who inspired Martinez to abandon her allegiance to her beloved San Francisco 49ers to support his Rams, if only for one weekend. Kinerson grew up a Raiders fan but also cheers for the Rams, having monitored Corbett’s career since it began.

Corbett was always relatively big for his age, joyful, determined and enthusiastic about a family he’ll never forget. He mailed Kinerson a Christmas card while the Rams were mired in a battle for the NFC West, reciprocating the kind of loyalty he feels from afar.

“It’s truly an unconditional love that the tribe has shown me,” Corbett said Thursday via Zoom from Los Angeles. “It’s just an honor to be a part of that and to represent our culture and our people being from the same area and taking where life has brought me here. Truly love the community and the support that I’ve gotten from every single person.”

‘Pure passion’

Other tribal members believe Corbett is the first to play in the NFL, though that required the proverbial road less traveled. He arrived in Los Angeles by way of Sparks, where he grew up idolizing his father and brother, a former offensive lineman at San Diego State.

He reaffirmed Thursday that they remain his role models.

His mother, Missy, who runs a licensed daycare, suggested Corbett and his brother play peewee football, thereby unearthing a lifelong love within both of her boys. Their father, a longtime truck driver, would coach their respective teams when he could. Though he insists his younger son’s success is a byproduct “of pure passion on his part.”

As a freshman at Reed, Corbett penned a letter to himself that detailed his goals both on and away from the football field. He vowed to succeed at everything he did and pledged to play college football at West Virginia on either line, he hoped. But injuries during his sophomore and junior seasons stymied his recruitment and compromised his pursuits.

He wrestled, too, and was forced to monitor his weight, preventing him from packing on the pounds that college coaches desperately desire. Division III programs recruited Corbett, but no Division I program would offer him a scholarship when he weighed between 230 and 240 pounds during his senior year of 2012-13.

So he emailed Ken Wilson — now the head coach at UNR, then the assistant under Chris Ault and a longtime family friend — and asked if he could help him walk on. “Could you just put in a good word? Please help me get on that team and I’ll show them what I can do,” Corbett wrote.

As a matter of fact, Wilson could.

Wilson was leaving UNR to become the linebackers coach at Washington State, but was impressed by the perseverance and confidence that Corbett displayed in the email. Ault retired at the end of the 2012 season, and Wilson recommended to incoming coach Brian Polian that he allow Corbett to walk on without a scholarship. Polian obliged.

Corbett sat out the 2013 season as a redshirt and used the year to gain as much weight as possible. Every day, he’d eat several meals and snacks comprised of nutrients that key weight gain like protein and carbohydrates. Peanut butter and jelly sandwiches were among the staples in his diet. Sometimes, he’d eat four or five in one sitting.

“The food course was just unreal,” his mother said.

By the 2014 season, he weighed 280 pounds and was big enough to start at left tackle. Good enough to earn a scholarship. He started four years at left tackle and was an All-Mountain West first-team selection during his senior season of 2017, departing the program as a hearty 306-pound NFL prospect.

“It’s tough for me to think it’s anything out of the ordinary,” Corbett said this week at the Super Bowl. “It’s only me. I’m the only one I can rely on. No ones looking at walk-ons to get the job done. … It’s on me to break through those expectations.”

Finding a home

That sentiment, Corbett learned, would still ring true when he reached the NFL. He was drafted by the Cleveland Browns with the No. 33 overall pick in 2018 and discarded after 15 offensive snaps in 18 months with the organization, steeling his resolve yet again.

He’d graduated, married former UNR volleyball star Madison Morrell and uprooted his life to move to Cleveland, where he’d start one game during his forgettable tenure with the franchise. His mother attended a Week 4 affair during his rookie season against the Raiders in Oakland and was stunned by the disappointment she saw on his face when he didn’t dress.

“He felt like he was letting Nevada down,” she said.

The Browns saw a bust, but the Rams saw value when they traded a fifth-round draft pick for Corbett on Oct. 15, 2019, and paved the path for him to play Sunday in the Super Bowl. He pondered his future on the cross-country flight and focused on maximizing his opportunity in Los Angeles, then a team in desperate need of depth along the offensive front.

Corbett supplanted Jamil Demby as the starting right guard during Week 9 of the 2019 season and has played every offensive snap for the Rams in 40 of his 41 ensuing regular-season games. He hasn’t missed a postseason snap either and ranked 27th among 82 qualified offensive guards this season, per Pro Football Focus.

He’s found a home with the franchise and within his nuclear family. His son, Ford, is 17 months and joined him on the field late last month at SoFi Stadium to celebrate the NFC championship victory over the 49ers.

“His smile was just amazing. I could just sense how much happier he actually was (in Los Angeles),” his mother said.

Corbett’s parents and siblings arrived in Los Angeles on Friday to partake in an increasingly surreal Super Bowl experience. He’s a valuable cog on the NFL’s No. 6 scoring offense, tasked with protecting quarterback Matthew Stafford and opening holes for running backs Cam Akers and Darrell Henderson.

His Rams are four-point favorites against the AFC’s Cincinnati Bengals, and a victory Sunday would secure them a place in football lore.

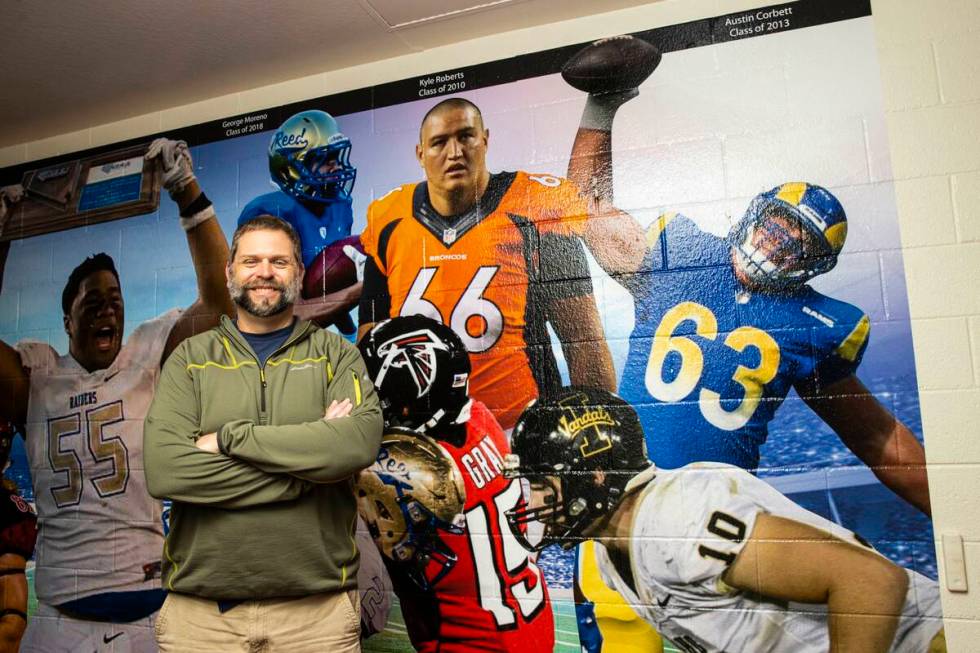

Corbett, though, is already immortalized inside the boys locker room at Reed in a mural that features the notable male athletes to star at the school. And at UNR, where his name is inscribed on a glass plaque next to other alumni that have played in the NFL.

“He remembers where he came from. He remembers his family. He remembers his roots. He’s never got too big to remember that,” Torres said. “Everbody’s going to be watching. To know that one of our tribal citizens is going to be out there playing his heart out is beyond exciting.”

Contact Sam Gordon at sgordon@reviewjournal.com. Follow @BySamGordon on Twitter.