Fanning the flames: Raiders, Steelers renew storied rivalry

The animus between the Raiders and Pittsburgh Steelers actually began on the eve of Dec. 23, 1972.

Outside Oakland’s team hotel the night before the teams played in the AFC divisional playoffs at Pittsburgh’s Three Rivers Stadium, a frothy, rabid crowd comprised of Steelers fans awaited Raiders players as they departed their team bus — eager to jeer and taunt their adversaries.

The crowd was so unruly that the Raiders needed a police escort from the bus to the lobby.

“They were supposedly keeping the fans away from us. And the fans are jumping in and talking smack,” said former Raiders tight end Raymond Chester. “In some kind of way, some fans breached our lines.” His backup, Bob Moore, was engulfed by the chaos.

One of the police officers tasked with protecting the Raiders mistook Moore for a fan and bashed him atop the head with his nightstick, opening a gash that would require stitches and limit his availability for the game the following afternoon.

“It was horrible. (Coach John) Madden was furious. Al Davis was furious,” said Chester, a four-time Pro Bowl honoree. “It literally transformed the game into a bloodbath. We were furious about it.”

And even more furious after the Immaculate Reception.

The encounter outside the hotel that night set the tone for a rivalry that would come to define the decade, featuring some of the game’s greatest players — along with brutal, savage playoff matchups in five consecutive seasons and one of the most memorable moments in NFL history.

The tenor of the rivalry has changed with the times and the rules, no longer featuring the gratuitous violence that once largely defined the NFL. But the legendary franchises will renew it on Sunday at Heinz Field, having not forgotten about the shared history between them.

“It’s really cool when you’re out there and you see the Steeler uniform, the Raider uniform,” Raiders coach Jon Gruden said. “It brings back some of the greatest games I could remember as a kid.”

‘Immaculate Deception?’

The crowd at Three Rivers Stadium was even more ravenous that Saturday afternoon, making every attempt to intimidate the Raiders — and the referees. Chester said he heard fans threaten officials. A typical occurrence at some stadiums, he surmised, but certainly not something that Oakland had experienced to that point.

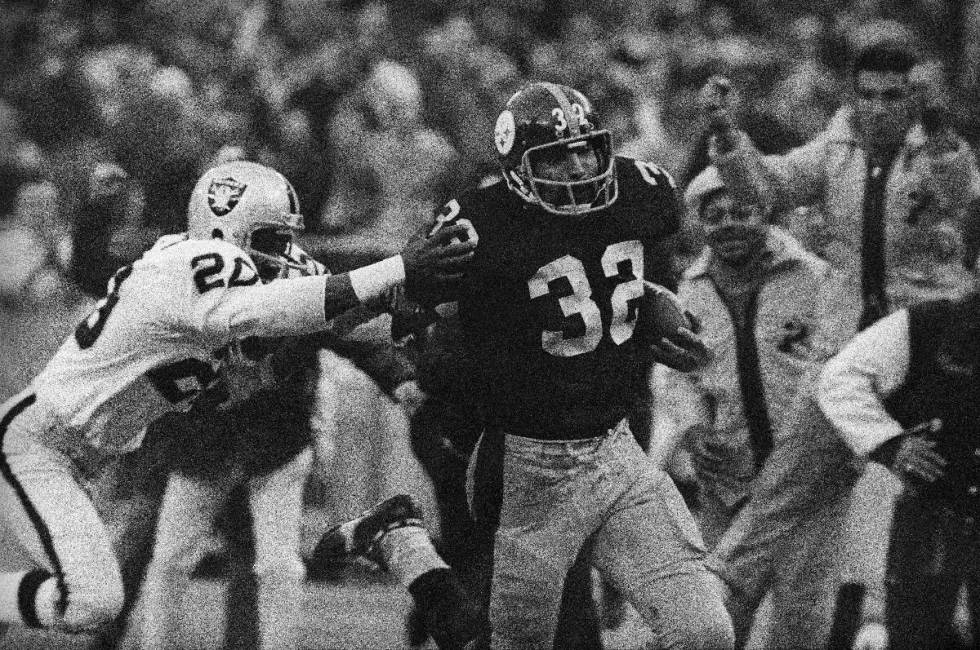

A defensive struggle ensued. With the Raiders leading 7-6, on the game’s final play, what the NFL Network deemed in 2019 as the No. 1 moment in NFL history occurred.

Steelers quarterback Terry Bradshaw dropped back to survey the field, eluding a pair of Oakland pass rushers as he rolled to his right. He fired a desperation throw downfield to running back John “Frenchy” Fuqua, who was leveled by Raiders safety Jack Tatum the moment the ball arrived.

It caromed into the air and into Harris’ outstretched arms before it hit the grass. He sprinted down the left sideline for what appeared to be the game-winning touchdown as time expired.

Fans rushed the field in jubilation while the Raiders waited for the officials to rule on the play.

“The crazy thing is, most of us didn’t even know what was going on,” said former Raiders linebacker Phil Villapiano, who was covering Harris on that play. “We’re not so sure if he caught it or not. No instant replay in those days. … John Madden is going crazy on the sidelines. And we’re like ‘What’s he going crazy about?’ ”

Well, at that time, the rules forbade offensive players from catching and advancing passes deflected by their teammates. The primitive replay systems in place didn’t provide the detailed review that modern replay allows, leaving the onus on the officials to make the proper call.

All the while, spectators surrounded the playing surface ready to react one way or another.

“You had the feeling that they were waiting to just attack,” Chester said. “The crowd was so violent and so pro Pittsburgh that I can honestly say the officials were terrified. I think they made the call that was in the best interest of their health.”

Touchdown.

The Raiders vacated the field, returning to what Chester described as a “horrible” atmosphere in the locker room. Tom Flores was in his first year on Madden’s staff as the wide receivers and tight ends coach and offered a similar recollection.

“It was quiet. It was almost silence like somebody had passed away,” Flores said. “(Madden) was visibly upset. He was pretty demonstrative for most of the time. There wasn’t anything he could do. It was a long trip home.”

Before the Raiders departed, Fuqua stopped by their locker room to speak to Chester, his teammate in college at Morgan State.

“He leans over and says, ‘The ball hit me. I hit the ball,’ ” said Chester, who jokingly referred to the play as the Immaculate Deception. “Obviously, he’s never told anybody else that. He may have said it in jest, or something like that, but that’s exactly what he told me when we were leaving the game.”

Fuel for the fire

The Immaculate Reception served to motivate the Raiders if nothing else. They knew they’d have to go through the almighty Steelers to reach their ultimate goal.

They played Pittsburgh five straight years in the postseason, still an NFL record.

They lost 17-9 to the Steelers during the 1973 regular season but exacted their revenge in the postseason with a 33-14 home victory in the divisional round.

“Every game we played against them, the rivalry would get more intense,” said Villapiano, also a four-time Pro Bowler. “All we wanted to do was beat those guys up. … It was never a normal game.”

The rules permitted for more physical play, and both teams would take full advantage, armed with Pro Football Hall of Fame talent.

Villapiano said other games were easy compared to those against the Steelers. Bradshaw claimed that nothing “gathered my attention for a full week” like a home game versus Oakland.

“On the road, I didn’t sleep because they were so dominant. What an awesome, complete football team,” Bradshaw said. “They were pretty much just like the Steelers.You knew it was going to be a hard game to win.”

The Raiders scored a 17-0 road victory over Pittsburgh early in the 1974 season, only to fall 24-13 at home in the AFC Championship to the Steelers, who went on to win their first Super Bowl. They didn’t play Pittsburgh during the 1975 regular season, but fell again in the AFC Championship as the Steelers rolled to their second straight Super Bowl.

“They were the team to beat,” Flores said.

And finally in 1976, they were the team the Raiders did beat.

Oakland stacked victories that year, clinching the AFC West before a showdown with the Cincinnati Bengals in the penultimate game of the regular season. Had the Raiders laid down, the Bengals would have won the AFC Central, thereby preventing the Steelers from qualifying for the postseason.

But Madden wouldn’t allow it, telling the team that “I’ve been hearing a lot of BS this week about us laying down. We don’t lay down. We come in the front door. We’re going to take these boys down tonight.”

They rolled to a 35-20 victory that ultimately allowed the Steelers to win the division and qualify for the playoffs. In the playoffs, the Raiders cruised to a 24-7 victory over their rivals en route to the first Super Bowl victory in franchise history.

That made it even sweeter in 1976 when the Raiders cruised to a 24-7 victory over the Steelers en route to the first Super Bowl victory in franchise history.

“I don’t think it would have been the same had we not beaten them on the way to the Super Bowl,” Villapiano said. “When you got the Raiders and Steelers, it was going to be a war. There was no prettiness. There was no faking. That was the mentality of the NFL.”

Remembering the rivalry

In hindsight, the rivalry between the Raiders and Steelers was rooted in respect as much as anything else. Sure, those games were more physical than usual, even by the standards of that era.

But that was simply a byproduct of the stakes of those games and the talent on the field.

”It was a battle for the baddest guys in the neighborhood. Who was the toughest,” Chester said. “It was the epitome of challenge and anticipation and war. And we loved it. … We fully intended to play as hard and as rough and tough as we were capable of doing, but I don’t think anybody had anything in their heart where they wanted to see anybody seriously injured or hurt.”

Chester remains friends with former Pittsburgh star defenders Joe Greene and Mel Blount. Villapiano said he’s attending the game Sunday with Harris.

The rivalry fizzled amid roster and personnel changes, with the two teams falling in and out of contention at various points in the last 45 years. Their last postseason clash followed the 1983 season, a 38-10 Raiders’ win in the divisional round that preceded the franchise’s last Super Bowl victory.

They’re 3-3 against Pittsburgh in the postseason and hold a 16-13 edge overall.

Gruden was in no mood to bask in the the nostalgia on Friday, though he did briefly pay homage to the Immaculate Reception and the droves of players now enshrined in the Pro Football Hall of Fame that participated in the rivalry when it was at its peak.

Raiders quarterback Derek Carr had a little more to say.

“We’ve had our fair share of battles in my career, too,” Carr said, including a 24-21 victory during the 2018 season in the most recent meeting between the storied franchises.

“As a football fan, I’m honored that I get to even step on the field at Heinz Field and get to play against these guys,” Carr said. “It’s cool for me as a fan, but as a competitor you want to … win the game.”

Contact reporter Sam Gordon at sgordon@reviewjournal.com. Follow @BySamGordon on Twitter.