Students on the move pose problem for Clark County schools

This is the second installment in a series, Year in the Life, which follows one at-risk Clark County School District senior as he works toward graduation — highlighting districtwide issues along the way.

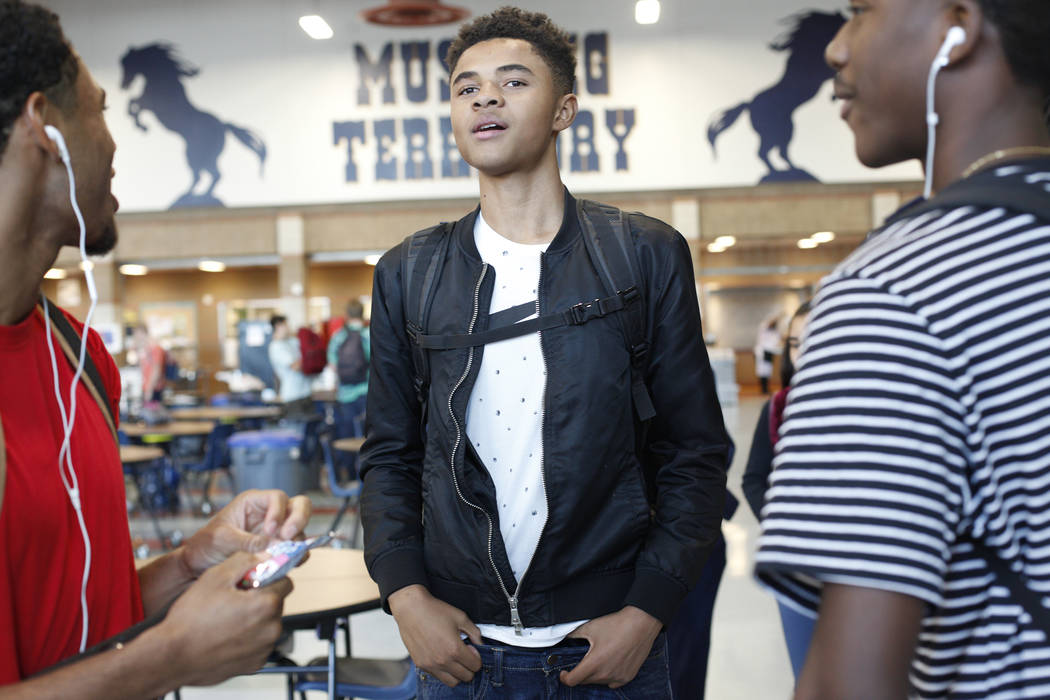

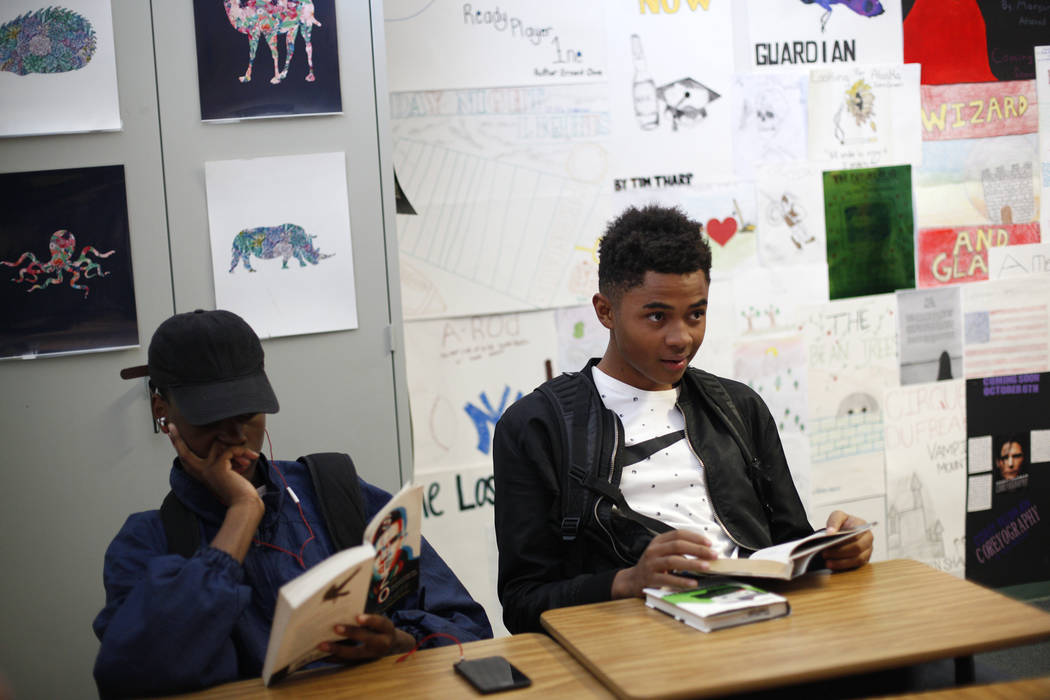

Six schools since sixth grade.

That’s the meandering educational route that D’Andre Burnett has traveled to get where he is today: a senior at Shadow Ridge High School who is racing to catch up so he can graduate with his classmates in about three months.

Before this year, Burnett was in danger of not getting his degree. But he got back on the right track and has been working to pass the classes he needs to graduate while still catching up on one he missed.

“I feel good about my chances to graduate now,” he said sitting in his counselor’s office last month. “I was scared at first. I was nervous.”

Burnett’s history of jumping from school to school made it harder for him to find his footing academically. It’s a story that many other students in the district share.

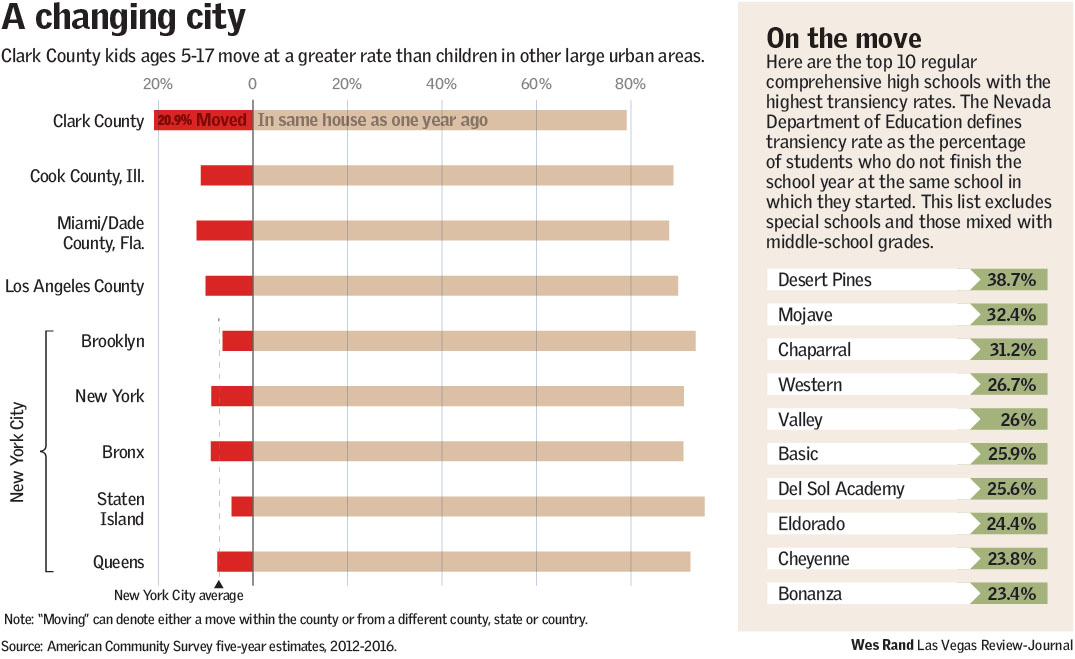

Given Las Vegas’ transitory population, it’s perhaps not surprising that the Clark County School District struggles with student mobility, or its transiency rate, which is defined as the number of students who finish the year in a different school than the one in which they started.

But the extent of the problem is eye-opening: Students here are about twice as likely to move during a given school year than their counterparts in Chicago, Miami, New York City or Los Angeles.

That mobility can have a significant effect on academic achievement, experts say.

“There’s these holes that develop in the students’ learning, where they may fall behind in mathematics or reading,” said Chief Academic Officer Mike Barton. “Once they start losing skills or not being taught certain concepts, those holes just start getting deeper as far as not understanding material.”

Transiency also has an adverse impact on high school graduation rates, a key component in the state’s school ranking system, forcing administrators to try to track down students who have suddenly disappeared from school.

But with the problem outside the district’s control, administrators can only try to assimilate newly arrived students while simultaneously playing detective to track down those who have suddenly left.

Moving around

Burnett’s middle school years went relatively smoothly. He spent sixth grade at Swainston Middle School in North Las Vegas and seventh and eighth grades at Cadwallader Middle School in Las Vegas.

His high school years were more turbulent. After a fight with his stepfather and mother when he was in ninth grade, he moved to live with his father in Rialto, California, leaving Arbor View High School behind.

He found himself ahead of his classmates at his new school, where he finished ninth grade and began 10th. But he eventually longed for home.

“I just missed my sisters a lot,” he said. “Going from a household with siblings to a household by yourself, it was a very drastic change for me.”

Burnett returned to Arbor View during his sophomore year, but his life wasn’t so stable. By 11th grade, he had gotten into a fight and was sent to behavioral school.

Through the district’s “unreturn” policy, Burnett wasn’t allowed back at Arbor View, so he moved to Shadow Ridge, where he is now working toward what he hopes will be a May graduation.

Burnett is barely getting by. He has a 1.46 grade-point average, and he’s not proud of that.

“That was low, but at the same time I’m grateful because I could’ve failed one of those classes,” he said. “I’m just glad to still be on the right track to graduate.”

He now has an appreciation for what school stability would have meant to his younger self. He compares his school counselor, Natascha Carroll, to a coach for academics.

If he’d had her as a counselor all four years of high school, Burnett said, “it would be a whole different story.”

A districtwide problem

That lack of consistency affects many other students in Clark County.

The district’s transiency rate of 25.4 percent is slightly higher than the statewide average of 23.9, according to 2016-17 state data. That means more than one-quarter of all students changed schools by the end of the school year.

That’s not good for student achievement. A 2012 study by the American Sociological Association concluded that changing schools can mean losing roughly two weeks of instruction.

“We know academically that mobility is bad for kids. The research shows that,” said Stephani Wrabel, an associate policy researcher at the Rand Corp. who specializes in student mobility.

There are different types of mobility — moving after a school year ends or moving schools at the conclusion of elementary school, for instance — and a midyear move is most disruptive, Wrabel said.

“There are a number of other sort of community factors that come into play here, but it is highly correlated that kids who are from low-income families are more likely to move than their peers who are not,” she said. “When schools serve more of those kids, they’re going to experience more of that turnover each year.”

That’s the case at the high-poverty Desert Pines High School, which has the highest transiency rate among regular comprehensive high schools in the district.

That hampers student achievement, but it also hurts Desert Pines’ graduation rate.

When students move, schools must verify that they’ve enrolled or moved elsewhere, in accordance with federal law. If administrators can’t find the student, he or she is considered an unsuccessful transfer — and becomes part of the school’s dropout rate.

A blow to graduation rate

Finding students can be tough, though, particularly if they move out of the country or to another state without informing the school.

Last year, Desert Pines had 91 unsuccessful transfers. Principal Isaac Stein said that for every six to seven of those students, the school’s graduation rate drops by 1 percent.

“So before we even get started, those 91 students impact our graduation rate significantly compared to other schools that do not have as high of a transiency rate or unsuccessful transfers,” he said.

The turnover also can hurt teacher morale, Stein said.

“It really affects our teachers and our retention of teachers, that our teachers invest quite a bit of time building really effective relationships, getting students to college and getting students graduated,” he said.

Students who enter the school midyear also pose a challenge, as they may be behind on credits.

That’s what the school’s Teaching and Learning Center aims to address. The credit-retrieval program allows students to make up for lost time through online classes.

A block schedule, in which students take four 88-minute classes a day, also makes it easier for students to catch up on back credits, Stein said.

“That’s really been kind of my vision for the school, is make sure that if a student walks in the door, we have a pathway towards graduation for that student, whether they’re credit-deficient or whether they’re an AP student,” he said.

No clear solution

Wrabel, who co-authored a book on student mobility, said there are things schools can do to help make it easier for students in transition. That includes having an updated website and providing helpful information for new families.

On the flip side, schools can help other schools by preparing students who are leaving, she said.

“If you know a student is going to be departing and moving, helping them, making sure they know where do we get a complete student record, maybe taking photocopies of the textbooks,” she said by way of example. “Communicating what that student has just recently learned so that they have an easier time pacing them or catching a student up.”

Barton, who has seen the transient nature of the valley during his decades in the district, said schools also need to get creative in figuring out solutions.

“All of our educators are very aware that this is an issue,” he said. “But how we try to solve the issue of transiency … it’s a tough one, because it’s sort of outside of our purview.”

Though his journey was tough, Burnett’s history of hopping schools may soon have a happy ending.

“I feel — not really proud,” he said, reflecting on his possible future graduation. “I just feel like it’s like a weight is coming off my shoulder. Now it’s to the next step to, like, a new chapter.”

Contact Amelia Pak-Harvey at apak-harvey@reviewjournal.comor 702-383-4630. Follow @AmeliaPakHarvey on Twitter.

First part of Year in the Life series

One student's story highlights Clark County schools' struggle with violence