Las Vegas police officer describes how ‘world crashed down’ on Oct. 1

“Where do you start?”

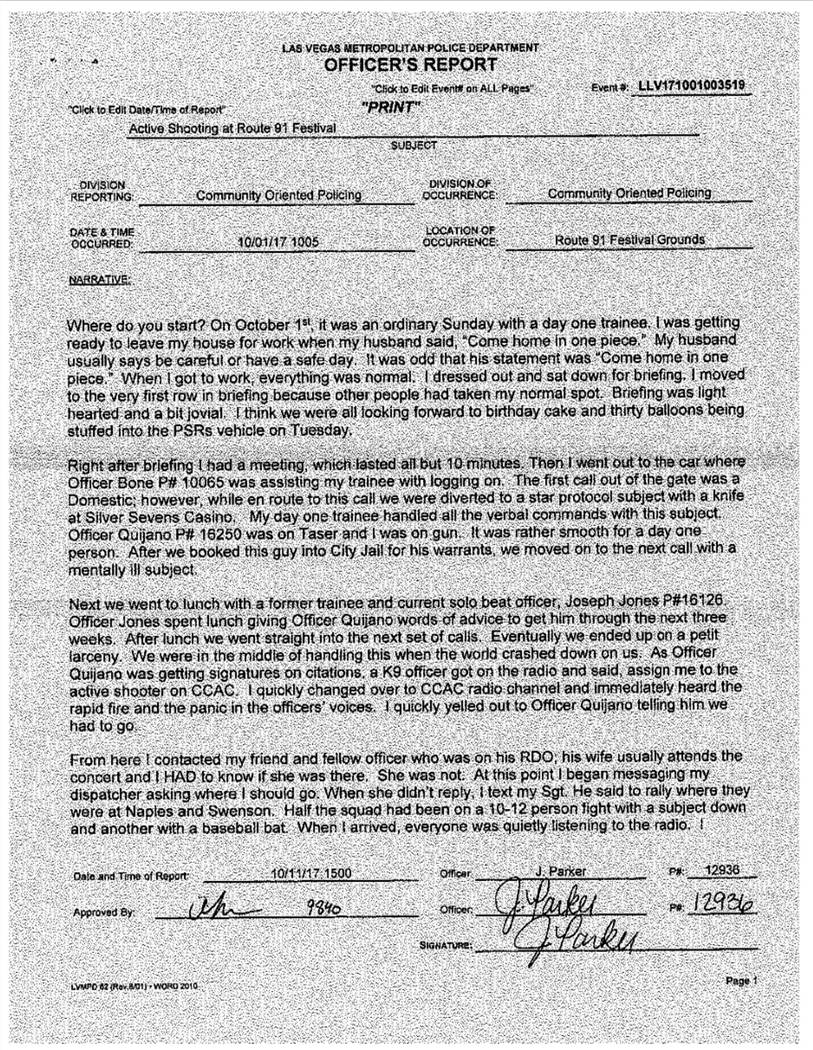

That’s how officer Jennifer Parker began her five-page report about the events of Oct. 1. The report is dated Oct. 11.

“On October 1st it was an ordinary Sunday with a day one trainee,” she wrote. “I was getting ready to leave my house for work when my husband said, ‘Come home in one piece.’ ”

That’s odd, Parker thought. Usually he told her to be careful or to be safe.

Parker’s report was one of hundreds released under court order this week by the Metropolitan Police Department, but it stands out because of its extraordinary detail and insight into what it was like to be an officer on duty that night, when a gunman killed 58 people and injured hundreds of others.

Her shift began normally. She dressed out and sat down for a briefing.

She sat in the front row because someone had taken her normal spot. Everyone was “jovial,” she wrote.

Parker went to another short meeting and then went out to her car to help her trainee log on.

Their first call together was a domestic disturbance, but Parker and the trainee, officer Samuelito Quijano, soon were called to the Silver Sevens, where a suspect had a knife.

“After we booked this guy into City Jail for his warrants, we moved on to the next call with a mentally ill subject.”

Next was lunch with a former trainee of Parker’s, who gave Quijano words of advice.

“Eventually we moved on to a petit larceny. We were in the middle of handling this when the world crashed down around us.”

Like hundreds of other officers that night, Parker switched over her radio to the Convention Center Area Command channel. She recognized the rapid gunfire immediately.

“I quickly yelled out to Officer Quijano telling him we had to go.”

To the rally point

After contacting her sergeant, Parker and her trainee went to a rally point at East Naples Drive and Swenson Road.

“When I arrived, everyone was quietly listening to the radio. I requested that I be given something to do.”

Her sergeant brought her back to her own training: They had to consider that there might be a secondary attack and therefore should not converge all resources on the initial event.

“As this was happening, someone drove up to us asking where the nearest hospital was because they had a gunshot victim in the back of the car.”

In the vehicle, Parker and another officer found a man with a gunshot wound to his back. Another trainee helped load the victim into a patrol vehicle.

“Sgt. Johnson yelled out, take two patrol vehicles. I screamed, I’ll go.”

On their way to the hospital, Parker made Quijano call someone in his family to report he was OK.

“This job takes a toll on all of us including our families. I didn’t want his wife wondering if he was okay.”

At the hospital

When they arrived at Sunrise Hospital and Medical Center, it was ready.

“Everyone that could come out of the hospital was outside with a bed or chair waiting in the area that the ambulances usually park.”

Parker thought, “How did they know?”

She found out four days later that an officer was at the hospital for an unrelated incident when he heard the radio traffic about the shooting and was able to prepare staff for “what was coming.”

“It comforted me to see them standing at the ready when I arrived.”

Then time stopped for her.

She texted her sergeant, who said she could stay, as long as she remembered to “keep her head on a swivel.”

“At this point it was like a floodgate had broken and the flood of injured poured over us,” Parker wrote.

Ambulances, Ubers, cars and trucks brought victims in by the dozens. People were screaming out the location of their injuries: back, chest, leg.

“I grabbed one lady out of a vehicle that had two tourniquets — one on each leg. I asked her to sit up and scoot toward me. I helped her on a gurney and they wheeled her away.”

At one point a four-door truck drove up. It had three bodies inside, and only one person was alive. Barely.

Then more victims arrived.

“I took one man who was holding pressure on his own chest wound.”

Parker escorted him back to the hospital’s trauma center and then returned to the front entrance, where she began directing traffic.

“It was like a revolving door, the ambulances would arrive with lights and sirens on and leave just as quickly with lights and sirens on.”

It was 10:39 p.m., 34 minutes after the shooting began, when Parker finally called her own family to tell them she was OK.

“I must have sounded not ok though.”

Blood was everywhere.

”The floors were covered with blood, the wheelchairs were covered with blood, and the gurneys were covered with blood.”

There was no time to clean. Parker fielded questions from anyone and everyone at the packed hospital.

A shirtless man wanted to know if she had a shirt.

A Japanese tourist and his daughter wanted to know if they could go back to their hotel.

A woman approached, carrying a little boy separated from his mother and aunt at the concert. She said he was lost.

Parker was afraid the boy might be going into shock and quickly walked him over to pediatric nurses. She gave him her card, and told him that if he gave it to any officer, they would find her. Parker had the mother’s name and knew she had rainbow-colored hair.

“I walked around the emergency room looking at every person to see if anyone had rainbow colored hair. I couldn’t find anyone.”

More victims poured in. Officers had to separate family from traumatized victims, because those without injuries weren’t allowed in the emergency room.

A vehicle arrived with an injured woman who was “passed out and limp.”

“A citizen ran over and helped me pull her from the car. As the woman was rushed into the hospital a passenger of the vehicle ran up, yelling that’s my wife. The man was still clutching onto his 24 ounce can of Bud Light.”

At some point, officer Quijano had assumed the task of identifying all the injured.

“Outside at the emergency room entrance you could hear the screams of family members who were finding out that their loved ones did not survive. Strangers began consoling these individuals as best they could.”

A makeshift morgue was set up. Officer Charles Hartfield was the 12th person to be declared dead at the hospital, according to Parker’s report.

“I was able to see him in the makeshift morgue,” Parker wrote. “He had on these amazing cowboy boots that had the American flag on them.”

At 4 a.m., cleanup finally began. “The hospital went from smelling like blood and death to smelling of bleach.”

Near the end of the night, Parker asked her trainee if he was coming back to work the next day. Without hesitation, he said yes.

“There was so much raw emotion everywhere — agony, fear, panic, determination, strength, love, and even calmness.”

Back at ground zero

Returning to the scene on Oct. 3 filled Parker with emotion.

“I began putting the victims and the scene together. There were dirty footprints everywhere fleeing from gate 5 and going down the sidewalk and toward the Catholic Church. It sucked to walk through there knowing and remembering that the victims at Sunrise hospital had dirty feet.”

Parker concluded her report by noting that she became part of a diverse team that had a common goal on Oct. 1 — “providing assistance and security at a traumatic and chaotic time.”

“No one was wrapped up in their title, their rank, their position, or their responsibilities,” she wrote. “If there was a need someone filled it that night.”

Contact Madelyn Reese at 702-383-0497 or mreese@reviewjournal.com. Follow @MadelynGReese on Twitter.

Related

Reports says Las Vegas gunman's girlfriend often stayed at Cosmopolitan

Woman's good deed after Las Vegas shooting nearly went bad

Officers' accounts detail heroic acts at Las Vegas shooting