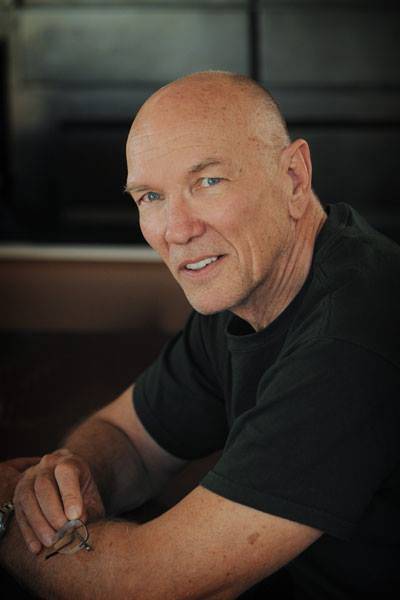

H. Lee Barnes explores melancholy themes in new book

The title of H. Lee Barnes’ latest book is not just apt, it’s kind of apropos.

“Life Is a Country Western Song.”

It’s apt because, like the best country-western songs, the short stories in the collection reflect the breadth and depth of everyday human experience. And it’s apropos because its release comes with the longtime Southern Nevada author and teacher’s move to more rural surroundings in northern Arizona.

About a year and a half ago, Barnes retired from full-time teaching at the College of Southern Nevada and moved to, as he describes it in a tone that makes you wish you were there, “the middle of the Hualapai Valley, 26 miles north of Kingman.”

“The area is great, and the Hualapai Mountains are wonderful places to hike and camp,” explains Barnes, who bought his five-acre property about five years ago.

On the other hand, it’s also just “130-something miles” from Las Vegas, so Barnes isn’t finished with Southern Nevada yet. “I’ll probably be back teaching in the fall. At least one class.

“I miss the classroom,” the plainspoken-as-ever Barnes adds. “I don’t miss the silliness.”

Teacher, mentor, author

Barnes, 74, taught for five years as an adjunct professor at CSN and then for 20 years as a full-time professor, along the way becoming a mentor to a generation of Southern Nevada writers and a must-read author among fans. Barnes was inducted into the Nevada Writers Hall of Fame in 2009 and has won multiple awards for his work, much of which explores the contemporary West and Westerners with sympathetic but wide-open eyes.

Barnes always has been a Westerner, in heart if not always geographically. Born in Idaho, he joined the U.S. Army at 19, and served as a Green Beret with Army Special Forces for three months in the Dominican Republic and a year in Vietnam.

After his service, Barnes returned to Nevada, where he built a resume heavy on law enforcement — Clark County sheriff’s deputy, state narcotics agent, private investigator — and was a dealer in Las Vegas casinos. Barnes recalls finding Las Vegas circa 1966 to be a city of “bigger-than-life characters” and small-town sensibilities.

“The general environment in Las Vegas, it was a small town, but it was a big small town, and you could develop friendships pretty easily,” he says.

“All the different people you knew might know somebody else, and one day you’re sitting at a bar to have a drink and meet somebody who knows 10 people you knew.”

Serious side of Vegas

It was while working in law enforcement that Barnes began to develop an appreciation for writing.

“One of the things you do when you’re a policeman is you write reports,” he explains. “And you have to be clear and you have to be concise because attorneys, if you’re on the witness stand, will try to use that report to undermine your story.

“I found I kind of enjoyed it. I enjoyed constructing the sentences. I learned the process of writing.”

Geoff Schumacher, senior director of content at The Mob Museum and a veteran Southern Nevada editor and writer, says Barnes is “really devoted to words and sentences in a very Hemingway sort of way. He takes words and sentences and phrases very seriously. There are not a lot of wasted words in a Lee Barnes story.”

Barnes — particularly in his 2003 novel “The Lucky” — also brought a seriousness to Las Vegas fiction, Schumacher says, making the city “not just a backdrop for a pocket book but the backdrop for a serious literary exploration.

“He is not someone who is taking potshots at Nevada or Las Vegas. That’s why we can take him seriously. He’s not doing what he does to get attention. He’s trying to understand people who live here, why they live here, what they do here and why it’s hard.”

Barnes earned a bachelor’s degree at UNLV and a master of fine arts degree at Arizona State University, where he began teaching as a graduate student. During more than two decades at CSN, Barnes was an advocate for promising students, doing “everything I could to help them get published in order to get their voices out there.”

The melancholy West

He also wrote award-winning novels, short stories and nonfiction of his own. His latest, “Life Is a Country Western Song” (Baobab Press, $16.95) is true to its title, wrapping itself around “anything that can exist in country songs,” including love, longing and loss, with characters living out personal dramas unnoticed and sometimes against the backdrop of bigger events.

Although, Barnes chuckles,” I don’t have any pickup jokes.”

“But all of these images are in there. What I wanted to do was capture the idea of the contemporary West, as I understand it, through my characters. In many ways they are searchers and, like all searchers, are looking for that happiness, but happiness isn’t necessarily there.

“In this particular collection, what I wanted to resonate was the sense of melancholy. If you listen carefully to a lot of lyrics, along with the music and voices, you get a sense of melancholy out of many country-western songs. And that’s different than sadness. It’s not depression.”

It’s about “not being able to let go of loss.”

Thanks to the decades he has spent here, he’s often referred to as a “Nevada author.” Does he ever resent that characterization as being, perhaps, too limiting?

“No,” Barnes answers with a laugh. “I don’t have that kind of ego.”

Contact John Przybys at jprzybys@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0280. Follow @JJPrzybys on Twitter.

An excerpt

From "The Day Nixon Was Impeached," a short story that appears in H. Lee Barnes' "Life Is a Country Western Song":

Eddie and Jace ran a cut-rate parts distributorship out of a storage shed in the Pettibones's backyard. Be it engine, carburetor, or transmission, J & E, as the partners called themselves, filled the order. If such a talent exists, both had perfect pitch for engines. They'd listen as a car turned a corner and by hearing it accelerate, identify the components in its power package. Eddie was the thief of the enterprise and Jace the chopper half. Pickup jockeys, airmen from Holloman, and even a few repair shop mechanics bought parts from Jace. On occasion he souped up a stolen car that Eddie would later unload in Juarez. As long as Eddie's projects left no oil stains, our parents overlooked the odd set of headers, gearbox housing, or carburetor lying in the backyard. They also seemed to have forgotten the six-month sentence he served in the state reformatory for car theft as well. After all, the state said he was reformed.

Eddie had pulled me out of more than a few scrapes, so when he called the last Tuesday in July and told me to pack clothes and be ready to stay overnight, I didn't question him, and when shortly after high noon he blew the horn of a red '70 GTO, I grabbed my overnight bag off the couch and hurried out. Eddie threw open the driver's door and stepped out.

"Nice wheels," I said.

He nodded. "Yeah, get in the back."

I tossed my bag onto the seat and slid in behind it. Gloria sat shotgun. He hadn't said anything about her coming along, but I knew better than to ask why, just as I knew better than to ask where he'd gotten the car or our destination or the purpose behind the trip. Gloria glanced back as I settled in.

The soldier's story

H. Lee Barnes' body of work includes critically lauded books and short stories that revolve around soldiers and military veterans. But he found his first military-oriented manuscript a tough sell.

"In 1977 or 1978, I wrote a book called 'Scriptures.' It explored a lot of things that I thought were important about Vietnam, not politically but simply about (soldiers') experiences," he says.

"I had an agent who loved the book, and she sent it to about six or seven publishers, and I got strange rejections. It was rejected not based on the book itself, but — of course, keep in mind this is the hangover from the antiwar movement — I got a lot of rejections based on, 'The nation isn't yet ready for a book like this about Vietnam,' which is the wrong reason to reject a book."

"So, the chance of early success with Vietnam eluded me, and I turned my writing into different directions," says Barnes, who 20 years later reworked some of the book's themes into other stories, among them those that appeared in 2000's "Gunning for Ho: Vietnam Stories."

Barnes says one of his toughest books to write was "When We Walked Above the Clouds," a memoir of his Army Special Forces experiences.

The book has received uniformly positive reactions from veterans, and Barnes hopes that it "will someday be discovered in another way and maybe looked at as not just literature but have some historical significance, because most of the people who've written about Special Forces have not been members of it. I wanted to write about the people who were there and what they experienced.

"If you've ever seen a mother cry over her dead son, you'll never forget it. She can be Vietnamese or American or Iranian, it doesn't matter. That's a mother mourning her son, and those (experiences) go deep into your heart and stay there.

"Those were the things that shaped me," Barnes says. "That's why I want that book to endure."