After 34 years, UNLV professors still digging Maya ruin in Belize

The ancient Central American city of Caracol was abandoned by the Maya almost a thousand years ago, but Arlen and Diane Chase can’t seem to stay away from the place.

Since 1985, the husband-and-wife team of UNLV anthropologists has spent several months a year at the remote site in the jungles of Belize, excavating ruins and uncovering secrets from the region’s once-dominant civilization.

The Chases just finished their 35th consecutive research season at Caracol.

“Which I think is a record,” Arlen said. “I don’t think that there’s another Maya project that’s been running continuously for this long.”

“With the same people,” Diane added.

The Chase-led Caracol Archaeological Project has excavated more than 400 buildings ranging in size from small residential groups to a central complex that is 14 stories high with a square base large enough to cover two football fields.

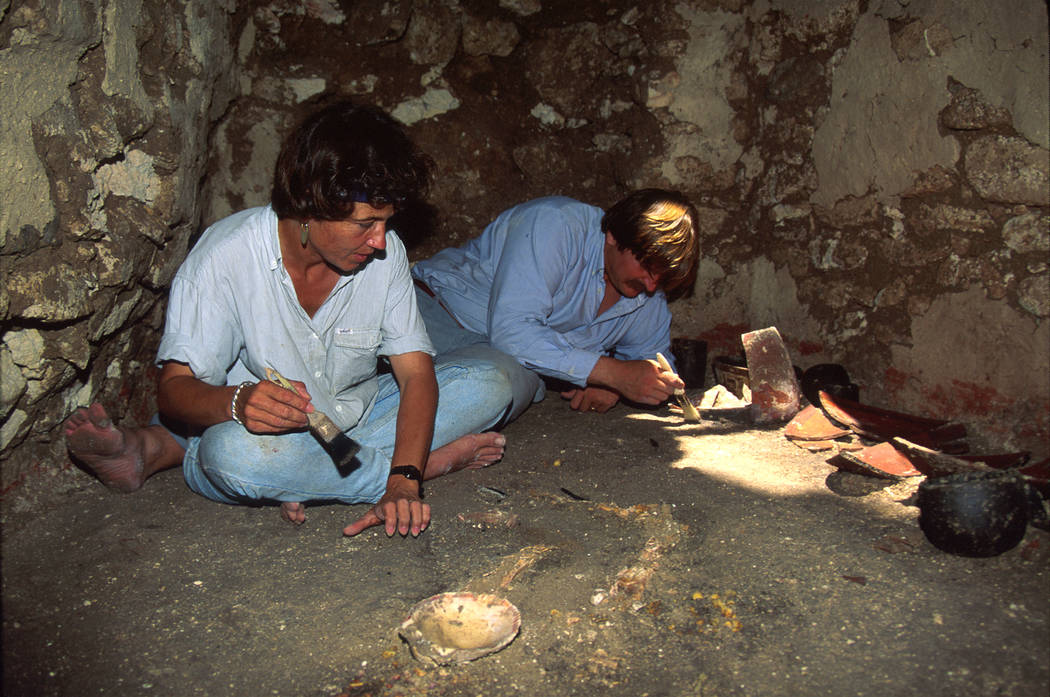

They have also unearthed hundreds of thousands of artifacts, including whole pottery vessels, tool-making debris and the bones of almost 800 people.

Along the way, the couple raised three children, who got to skip school and travel with their parents during field work season but still had to do their homework.

Their eldest son, Adrian, now holds degrees in anthropology and computer science from Harvard and a grant from the National Science Foundation to study Caracol alongside his mom and dad.

An ancient metropolis

The couple’s work in Belize over the past three decades has led to a new understanding of ancient Maya culture, economics and collapse.

Using hieroglyphic texts and evidence on the ground, Arlen and Diane have determined that Caracol was first settled sometime after 600 B.C. and likely peaked around A.D. 650 after its army defeated the neighboring Maya kingdom at Tikal in present-day Guatemala.

Recent study of the city’s markets suggests the end came roughly 300 years later, preceded by a societal breakdown that saw the ruling elite hoarding imported goods once widely available to many city dwellers.

“There was no trickle down,” Arlen said. “What you have is a real 1 percent.”

Once thought to be a small place, Caracol actually ranked as one of the largest cities in the Maya world, with a population that likely exceeded 140,000 people and a footprint larger than Henderson.

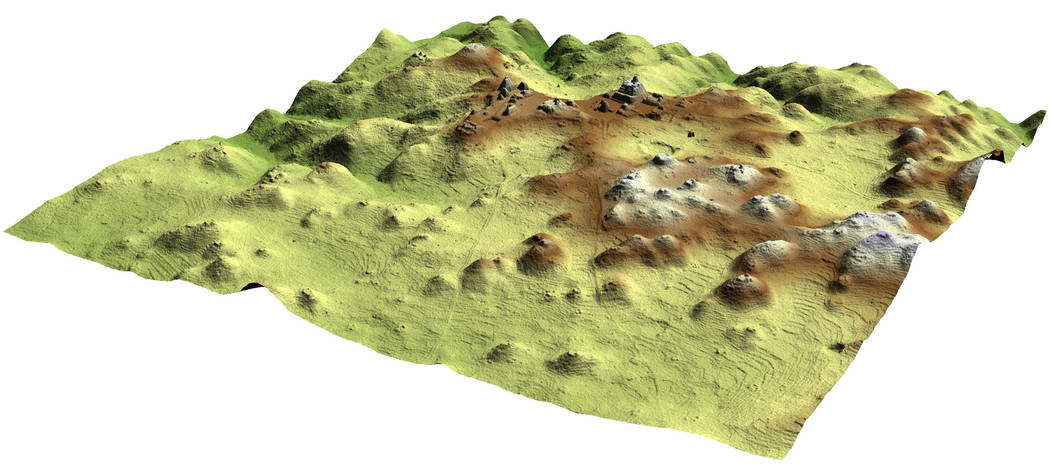

Arlen said it included roughly 125 square miles of terraced agricultural fields, residences, market plazas and other structures connected by a network of roads known as causeways.

“No one had any idea that it was as large as it is,” Diane said.

Early on, the Chases and their team painstakingly mapped the site on foot. Then in 2009, they pioneered the use of a laser mapping technology known as LIDAR to capture detailed images of the terrain beneath the thick tree canopy.

Arlen said it took them five tries to secure funding for the LIDAR flights because no one thought it would work in a jungle setting. They finally persuaded NASA to give them $417,000 from a grant program dedicated to space archaeology.

“For a year, all we did was look at these photographs,” he said.

“It turned out to be absolutely revolutionary,” she added.

Persistence pays off

The Chases fall into a rhythm as they discuss their work, taking turns offering corrections or building on a point the other was making.

Even their specialties seem to complement each other — his in the study of ceramics, hers in bones and graves.

“As you can see, we are fond of completing each others sentences,” Diane said after a while.

But they also come at things from different angles and frequently challenge each other’s conclusions.

“She’s a good editor,” he offered.

“We don’t think exactly the same,” she said.

Diane grew up in Long Island, New York. Arlen was a military brat who was born in Germany and bounced around before settling in California.

The two met at the University of Pennsylvania, where they each enrolled to study anthropology and ended up in the same dormitory building.

“I helped move her in on the first day,” Arlen recalled. “Then she wouldn’t talk to me for a year.”

Diane said Arlen tried to win her over by inviting her down to his dorm to see his small collection of books on the Maya. He also caught the train to Long Island once and showed up uninvited to a Sunday dinner with her family.

“I was persistent,” he said with a smile.

Lost city in the jungle

Arlen and Diane got married after they graduated in 1975 and spent their first field season together in Guatemala in 1977.

They made their first trip to Caracol in 1983.

The only way to get there then was a slow, teeth-rattling drive along 55 miles of old logging roads. “You couldn’t count on getting into the site or getting out in a single day,” Diane said.

The ruins were hidden by mounds of sediment beneath a dense, old-growth forest. “We couldn’t see what it was we were supposed to be doing,” Arlen said, but Belizean officials persuaded them to commit to a 10-year exploration of the site.

When they began their first field season in 1985, their drinking water had to be flown in by a British military helicopter. Diane said the only way they could call for help was to climb to the top of a pyramid with a radio tuned to a frequency used by the U.S. Embassy in Belmopan, Belize, more than 60 miles away.

Artifact thieves had set up camp all around the site. One of the looters left a warning tacked to tree along a main path to the ruins. On a flattened cigarette carton, someone had written in Spanish: “We are the archaeologists here.”

But the Chases said they’ve never had any real trouble at Caracol, probably because they are rarely there by themselves. Each year, they are joined by a team of about two dozen college students and local workers, some of whom have been employed by the project for decades.

More to be learned

These days, the site is protected by resident caretakers, security guards and the Belizean military, which conducts regular patrols in the jungle between the ruins and the Guatemalan border, Arlen said.

As more of the ancient city has been unearthed and stabilized, it has become an important tourist attraction for the New Jersey-sized nation. Arlen said it is certain to become a World Heritage site some day.

But it still isn’t easy to get to, especially during the rainy season.

That’s why the Chases limit their field work to the driest months of the year to avoid flooded dig sites and washed-out roads. Also frogs, “thousands and thousands of frogs,” Arlen said.

“We thought it was cool. Once,” Diane added.

The Chases joined the faculty at UNLV in 2016 after 30 years with the University of Central Florida. Both are professors in the Anthropology Department, but Diane carries an additional title: executive vice president and provost.

Her duties as UNLV’s chief academic officer have cut into her time in Caracol in recent years, but she still makes it to the dig site, usually at the beginning and the end of the field season.

“I need her to come down and do the bones at the end of the season,” Arlen said.

Diane said they already have plans to return to Caracol next year, and they will keep going back as long as there are interesting things to find and interesting questions to answer.

“The site has helped us learn all sorts of things about the Maya. We know about city planning. We know about economics. We know about agricultural systems. We know about rise and fall and warfare,” she said. “It has been a great place not only to learn about the Maya but to learn lessons about today.”

Contact Henry Brean at hbrean@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0350. Follow @RefriedBrean on Twitter.

More to discover

Detailed information about the Caracol Archaeological Project on its website, www.caracol.org.

If you find yourself in Salt Lake City, "Maya: Hidden Worlds Revealed," an exhibit featuring Arlen and Diane Chase's work in Belize, will be on display at the Natural History Museum of Utah through May 27.