The neon lights of Reno’s casinos beckoned Bea Aikens, and the thrill its blackjack tables and slot machines nearly ruined her financially before she got help and broke her gambling addiction.

Aikens, who now lives in the Las Vegas Valley, vividly remembers being a 28-year-old real estate broker in San Francisco unable to resist the siren call of Nevada’s gambling emporiums. Her finances were in shambles; so was her marriage. She couldn’t think straight.

But winning back her losses wasn’t what kept her coming back. It was the adrenaline rush from each win or jackpot.

“Money is not the drug,” Aikens, now 60 and 23 years into her recovery, said of those years. “It’s the delivery system to play.”

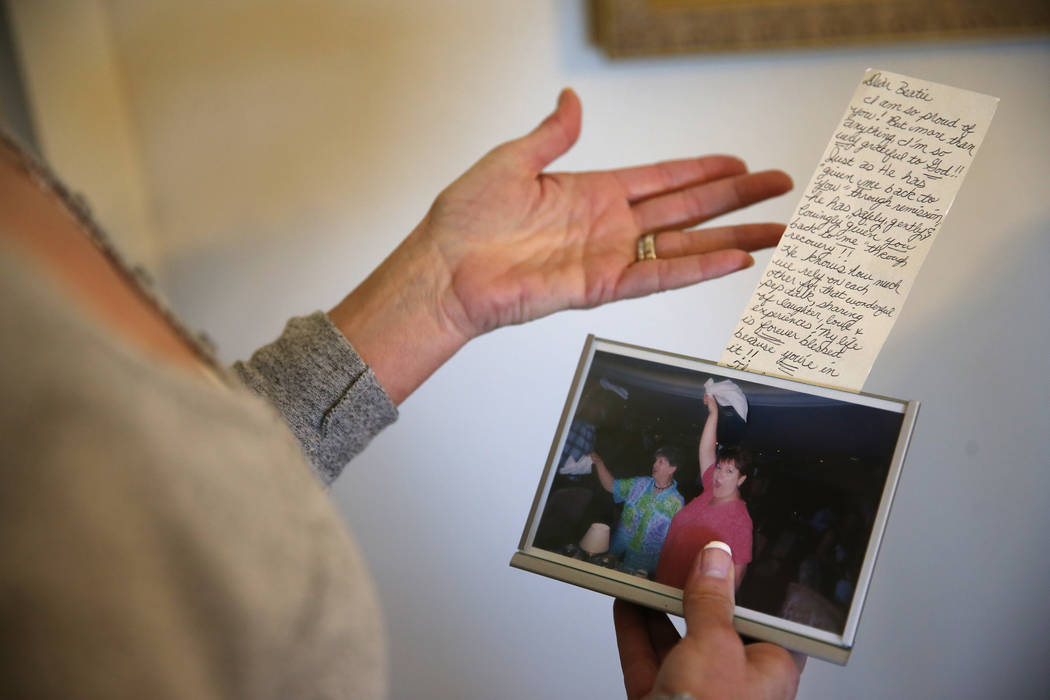

Aikens got help in January 1996, enrolling in a 12-step program followed with three months of therapy, and kicked her addiction. Later she founded a nonprofit that helps those in recovery from problem gambling.

The group is named Lanie’s Hope, after her sister, Lanie Shaffer, who died by suicide in 2008 after recovering from a gambling addiction only to relapse. She was 52.

Aikens didn’t know her sister had slid back into the throes of her addiction. She realized it when she discovered a plastic grocery bag overflowing with gambling receipts shortly after her death.

“She survived cancer, and she was killed by a disease you can’t see or diagnose in blood,” Aikens said.

Access increases risk

The National Center for Responsible Gaming, which uses contributions from casino companies to fund gambling research, says most studies estimate that roughly 1 percent of the U.S. adult population meets diagnostic criteria for the most severe form of gambling disorder. The National Council on Problem Gambling, meanwhile, says about one-in-five problem gamblers consider ending their lives at some point.

It’s not clear how many follow through on their destructive impulses, said Carol O’Hare, executive director of the state chapter of the latter group. Compiling such a figure would be nearly impossible, she added.

But there is evidence that proximity increases the risk of developing the disorder, according to Mary Drexler, program director for the Maryland Center of Excellence on Problem Gambling.

A state report in the early 2000s estimated that Nevada has a rate of problem gambling two or three times higher than other states around the country.

Since then, however, legal gambling has steadily grown and entered new U.S. markets. That extends beyond brick-and-mortar casinos to activities like sports betting, which 10 states have legalized so far.

And in Nevada and some other states, bettors who set up accounts with a local sports book or advance deposit wagering operators can wager online from the comfort of their couches.

“The more we expand into internet gambling, we will probably see an increase in problem gambling,” Drexler said.

The ‘hidden addiction’

Problem gambling is a disorder of the brain, and many people who aren’t familiar with it — including gamblers — mistakenly believe the bettor should be able to quit whenever they truly decide to do so, experts say.

The stigma surrounding problem gambling and the shame many feel for losing their savings or rent money also can prevent them from asking for help.

As a result, “gambling is much more a hidden addiction,” Drexler said.

When suicide and problem gambling intersect, it’s often because the gambling leads to other risk factors for suicide, like financial and relationship problems.

“If you continue to add these risk factors into the mix, the potential for suicide, logically, is getting higher,” O’Hare said.

As the longtime bastion of legal gambling in the U.S., Nevada has many resources for problem gamblers. In Las Vegas alone, there are up to 120 Gamblers Anonymous meetings weekly, or more than 17 a day, according to Aikens.

Nevada’s casinos also train employees to recognize signs of problem gambling and encourage them to steer customers exhibiting the indicators to available resources or encourage them to at least step away from the table for a period of time, said Alan Feldman, who develops responsible gaming policy for MGM Resorts International.

“All Nevada (casinos) must have a responsible gaming program, and that can be as straightforward as signage by all ATM machines,” Feldman said.

Still, that’s not enough. Feldman said he would like to see the state contribute more to prevention and research.

O’Hare agrees.

“While we’re treating the person today who has a problem, we need to be using that information to find better ways,” she said. “You have to say, ‘How do we do better?’”