For some Clark County valedictorians, it’s crowded at the top

Olivia Yamamoto graduated at the top of her class at Coronado High School in Henderson.

So did 29 of her other classmates.

Yamamoto is one of many valedictorians sharing the honor with multiple other students this graduation season. Numerous Clark County School District high schools, particularly those that are academically competitive, are featuring more than one No. 1 as they bid farewell to the classes of 2019.

Preliminary numbers from early May indicated that Palo Verde High School in Las Vegas would graduate 16 valedictorians, for example. Foothill High School in Henderson was expected to have 18.

The dilution of the honorable title, traditionally reserved for the single student who has the highest grades in his or her graduating class, is the result of a district policy on the books for years. It sets a GPA cap of 4.8 — the highest grade you can achieve with bonus points for taking advanced courses.

The Class of 2019, however, will be among the last to see large valedictorian pools following a change that eliminates the GPA cap starting with the Class of 2021. It’s part of an effort to bring uniformity to the way that schools calculate valedictorian and salutatorian status, while also allowing students who repeat courses to be eligible for the honor.

The change will likely make the title more exclusive — but current and former valedictorians note it will also make an already competitive academic environment even more cutthroat.

“There being no cap means that kids are going to start taking (Advanced Placement) classes in middle school and are going to overload their schedule with way too many AP classes,” Yamamoto said. “And that level of stress and abundance of homework, it’s most likely going to be a negative on their mental health.”

Reaching the current GPA cap of 4.8 already requires taking a medley of challenging courses.

Honors courses carry a bonus weight of 0.025 per semester. Advanced Placement or International Baccalaureate courses bring an additional 0.05 weight. There is a limit, however, to the number of such courses that can count toward the GPA cap.

The setup means that valedictorians can come from a variety of different backgrounds — some, like Yamamoto, may have taken 12 AP classes. Others may have only taken the number necessary to reach the maximum GPA.

But Yamamoto said she doesn’t feel that being one of many valedictorians detracts from the recognition.

“I honestly think it’s a good thing that so many of us can succeed like this, because I’ve known most of these people since elementary school,” she said.

Karen Bolano, one of several valedictorians in Las Vegas High School’s Class of 2017, said she still felt honored despite sharing the valedictorian title.

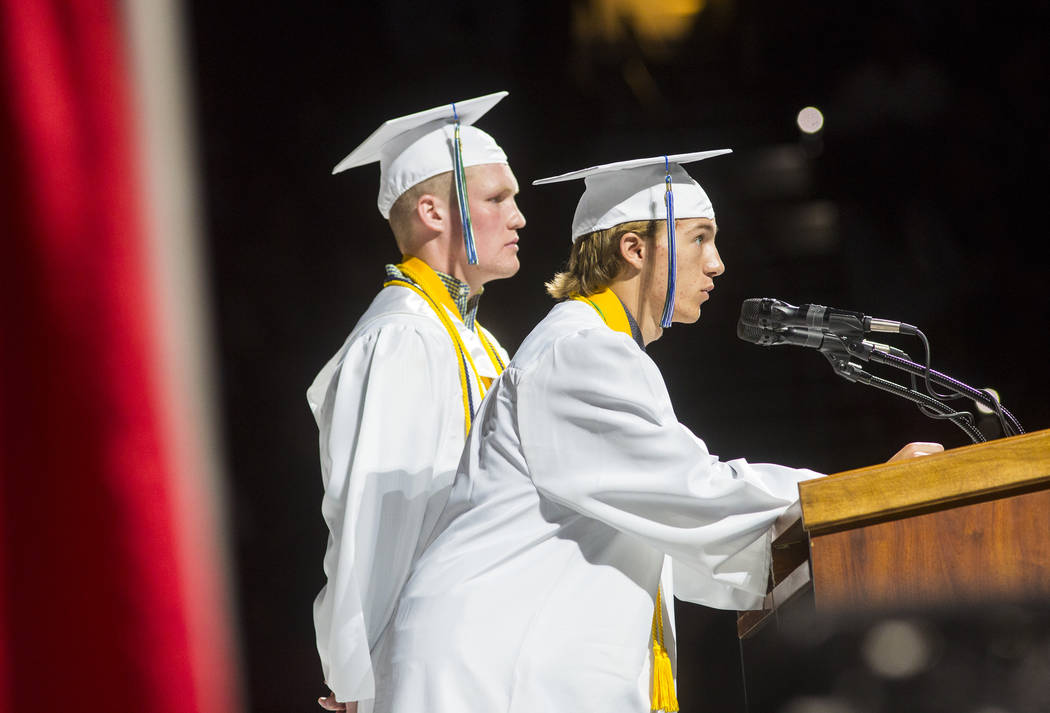

Nor was she worried about sharing her graduation speech with them. Each student got a few minutes to speak, she said.

“I didn’t feel like the environment was super duper competitive,” she said. “We just all wanted to be good and do good.”

But the elimination of the cap will definitely make things more competitive, she said, noting that she and her classmates would’ve done anything to get the highest GPA.

“A lot of us were planning from freshman year, middle school, ‘OK, we’re going to be at that number one spot and we’re going to work hard throughout high school to be there,’” said Bolano, now a UNLV student. “So (under the new system) we would’ve been way more stressed than we already were.”

Louis Shulman, who graduated from Coronado in 2017 as one of roughly 30 valedictorians, said he took it easier during his senior year while still earning the 4.8.

“I know that all I had to do was hit the cap and then (I) just kind of coasted,” said Shulman, who took nine AP courses. “Just made sure I got As.”

But without the cap, he said, he also would’ve pushed himself to do whatever necessary to get the top spot.

“I think I could’ve handled it,” he said of pushing himself. “I don’t know if that would’ve been necessary, but I probably would’ve been tempted to do it. And I know other kids would’ve been tempted to do it.”

Different schools, different rules

The push to change the policy sprang, in part, from the experience of one 2017 Coronado graduate.

Destiny Farley was about to graduate as valedictorian when she was informed she was disqualified from the title.

She had repeated two courses, geometry and Algebra I, in an attempt to get higher grades. She got an A the second time around in both, replacing a lower grade earned the first time. She later found that repeating the classes disqualified her for valedictorian status under a rule in place at Coronado.

She was absolutely demoralized.

“I carried that experience with me for (a while) and I still do, in some way,” said Farley, also a UNLV student. “I’ve never been a person who’s been good at handling failure because I don’t fail a lot — so that was like my first major blow.”

That rule, however, varies from school to school.

Farley would’ve been valedictorian at Sierra Vista and Spring Valley High Schools, for example, where they allow valedictorians to have repeated courses.

The new policy eliminates discrepancy, allowing students who repeat courses to be eligible for valedictorian or salutatorian status.

“This was our way of trying to ensure that students who have that will and aggressiveness to repeat a class, they should also be eligible for that standing,” said Mike Barton, the school district’s chief college, career and equity officer.

Does it matter?

Despite a competitive push to get to the top, college experts say being valedictorian does not guarantee college admission — if it’s even a consideration.

Lisa Sohmer, an independent college admissions counselor and former board member of the National Association for College Admission Counseling, says colleges still look at individual student accomplishments, examining whether a student has taken all of the advanced courses available to them and performed well.

“If there’s a cap, you’re going to hit it and if there’s not a cap, you’re still going to be in the very highest GPA(s) reported by the school,” she said.

Steve Maples, director of admissions for the University of Nevada Reno, said the school doesn’t take valedictorian status into consideration.

The school does its own GPA calculation, he said, and looks at whether students challenged themselves in high school.

Students like Yamamoto, after all, are more than a number. She was active in the Nevada Youth Legislature and the district’s Student Advisory Committee. Now she’s headed to Georgetown University in Washington.

Farley, meanwhile, said she’s trying to manage her competitive personality. She’s still shooting for summa cum laude in college — but to future high-school graduates, she says this: Don’t let the pursuit of honors consume you.

“That’s not all there is to you,” she said. “You being a valedictorian says nothing about who you are as a person, and it really doesn’t say much about what you’re going to contribute to the world.”

Contact Amelia Pak-Harvey at apak-harvey@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-4630. Follow @AmeliaPakHarvey on Twitter.