Out amid the sage and mesquite on the outskirts of the small ranching town of Overton lays a long, low pueblo replica, the likes of which were inhabited by an ancient people. A small oasis at the confluence of two rivers, the Muddy and Virgin, provided a haven for prehistoric peoples and ranchers alike. The Lost City Museum is a fascinating family destination with two local prehistoric archaeological sites that overlook the flood plains created by Lake Mead. The history behind this nearly 100-year-old museum is almost as interesting as the wealth of historical artifacts it houses.

“What sets Lost City Museum apart from other Nevada museums is that it was built specifically to interpret these ancient habitation sites,” said Museum Director Mary Beth Timm. “Its existence demonstrates how engaged individuals can positively impact future generations.”

Before Mormon settlers traveled down from St. George, Utah, to farm cotton, prehistoric peoples survived on small gardens containing corn and squash, gathered amaranth, mesquite, and pinyon seeds, and hunted deer, sheep, tortoise and hare. There was enough food and water, a precious desert resource, to support small family groups and villages.

As plans for the construction of the Boulder Dam were being finalized in the mid-1920s, local brothers Fay and John Perkins learned that the perfectly preserved sites that peppered the playa would eventually be consumed by the dammed waters of Lake Mead. Realizing the significance of the potential loss of these Ancestral Puebloan sites, the brothers brought the plight of the sites to the attention of Nevada Gov. James Scrugham, who put a plan in action to save the ancient pit houses and artifacts.

The Nevada governor hired noted archaeologist M.R. Harrington to direct the excavation of the sites to preserve this ancient and native way of life for future generations. Harrington had a deep understanding and respect for native sites and was associated with the Museum of the American Indian at the time.

In 1924, Harrington began this near 15-year project. The sites were rich in preserved artifacts such as baskets and tools, corn cobs, burnt squash seeds and grinding stones. They were a snapshot of how families lived, worked and survived in the harsh desert climate.

Houses and larders were typically left empty with few artifacts and food supplies. Sometimes, the houses were burnt to the ground as the people moved on. Harrington understood the significance of these many sites and labeled them the largest concentration Pueblo Grande de Nevada.

The detailed excavation work and wealth of artifacts that Harrington’s teams pulled from the desert floor were lauded by the press, which gave the area its unofficial name of “The Lost City.”

The Boulder Dam Park Museum was completed in 1935 by workers of the Civilian Conservation Corps to house much of what Harrington and his teams uncovered.

In the 1950s, the National Park Service turned operations of the museum and its replica pueblo and pit house over to the state of Nevada. The name of the museum was changed to the more enchanting Lost City Museum. It is listed on the National Register of Historic Places for its Depression-era buildings as well as its preservation of a people and time that has long disappeared from the sweeping desert foothills of Southern Nevada.

Since its inception, Lost City Museum has grown to include three exhibition galleries filled with original artifacts as well as pristine baskets from the Joseph F. and Kathryn A. Perkins impressive collection.

The largest exhibition hall is the Fay Perkins Gallery, which contains an actual archaeological site that was initially excavated during CCC’s excavation in 1934. Half of the exhibit shows the excavation that uncovered forgotten bits of pottery and a foundation that lay undisturbed for hundreds of years under layers of silt and sand. The other half shows how ancient peoples plastered their rooms, hearths and storage areas, evoking a prehistoric living room and pantry.

The museum shows two 20-minute videos that delve into the history of the people and the museum’s evolution and subsequent expansion. The Lost City Museum has created moving displays for guests to experience what life was like for the men, women, and children who lived along the Muddy and Virgin River banks more than 600 years ago.

The valley has long been home to other residents as well. Other “Lost Cities,” such as abandoned mining communities, the foundations of the city of St. Thomas, tools and the trades of the Civilian Conservation Corps and early ranching equipment show a sense of continued occupation as these two rivers continued to support a small ranching community.

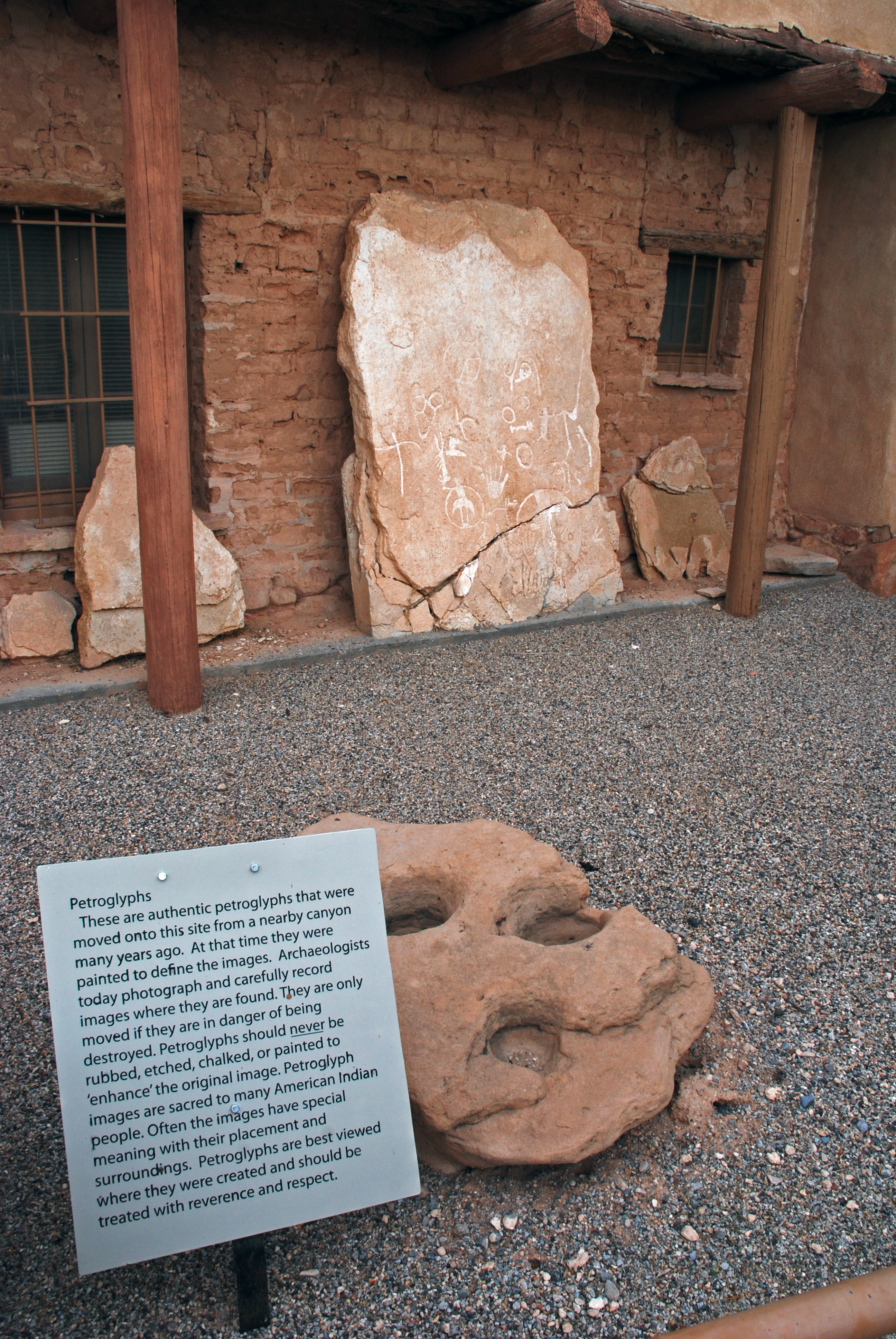

Outdoor exhibits include the pioneer garden, which features old ranching equipment and local pollinator plants to attract bees and butterflies.

As guests wind down their stay, the museum store offers authentic Indian jewelry and crafts as a reminder of their experience at the treasure-filled Lost City Museum.

Members of the editorial and news staff of the Las Vegas Review-Journal were not involved in the creation of this content.