UNLV at forefront of bid to replace traditional remedial classes

After UNLV sophomore Vince Briones failed his remedial math class for the third time, he faced a choice: Try once again in the fall or spend the summer in an intensive math course known as Math Bridge.

For him, enrolling in the latter was a no-brainer. “It’s my only way to get into the math class I want to get into,” Briones said.

The course runs for three hours per day, five days a week for five weeks and offers students who score below the UNLV cutoff for ACT math scores a chance to catch up and get into a math class that will count toward graduation. Now six years old, Math Bridge is part of an ongoing push to do away with traditional remedial classes.

Another new option, known as corequisite classes, will begin to roll out this year to help meet the goal of completely replacing traditional stand-alone remedial classes at the Nevada System of Higher Education by 2021. UNLV will be the first school to test the option.

The number of students unprepared for college-level math and English continues to grow at some NSHE institutions, while the graduation rates for students in remedial classes lag well behind those of their peers who start in college-level classes.

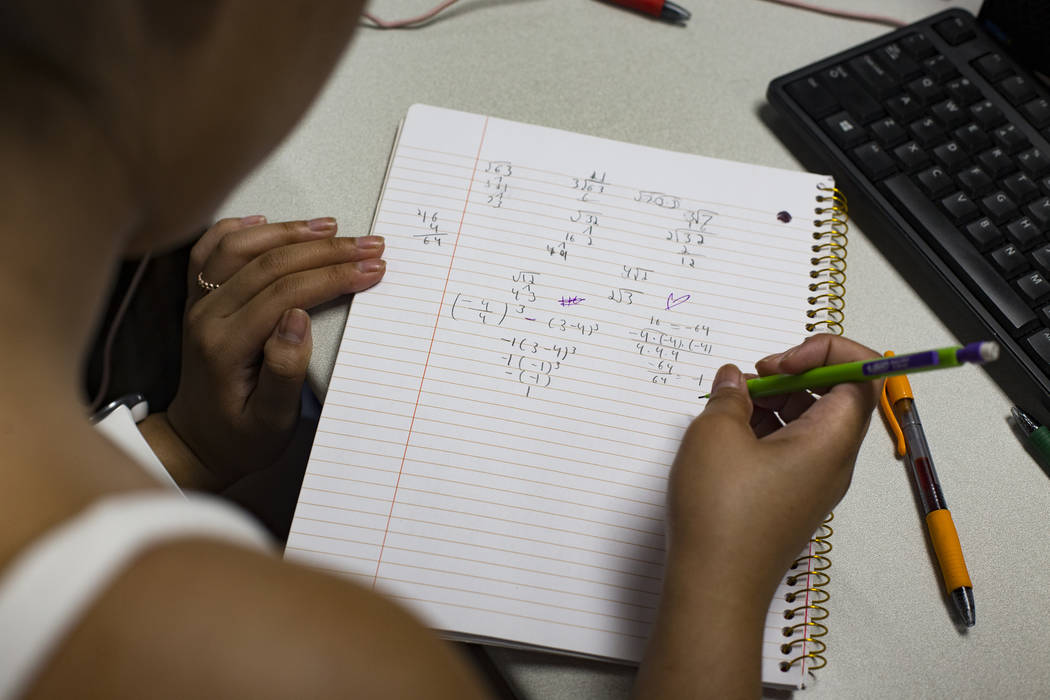

Through Math Bridge, Briones said he saw his scores improve dramatically in the first few weeks. He attributes that progress in part to a teaching model that emphasizes review and allows students to see where they struggle via an assessment system known as ALEKS.

Over 70 percent of the 300 to 400 students who enroll in Math Bridge each summer improve their scores enough to enroll in a college-level math class in the fall, according to learning programs coordinator Kayla Wright.

Graduation rates tell the tale

Students who take traditional remedial classes graduate at much lower rates than their peers who take only college-level courses, in part due to the extra semesters and costs that remedial classes tack on.

“It racks up when you fail a class and have to retake it,” Briones said.

At UNLV, 49 percent of students who never took a remedial class graduated in 2017, compared with 32 percent of students who did. At the College of Southern Nevada, just 9.5 percent of students who took remedial classes graduated within 150 percent of the expected time.

“It’s been an utter failure,” NSHE Chancellor Thom Reilly said of the remedial classes that students must pass before they are allowed to enroll in a credit-bearing class.

Reilly said the NSHE wants to move remedial education back to the high school level, by having seniors take such classes before they start college. Another priority is to share NSHE data showing remediation rates for the state’s high schools with educators in those schools.

“We need to find out where’s the disconnect between their curriculum and what we need,” Reilly said.

One disparity is evident in ACT scores. Last year, the state Board of Education approved a plan to lower the standard for proficiency below national standards, creating a class of students who are considered proficient by high school standards but not by those of NSHE institutions.

NSHE data show over one-third of all Nevada high school graduates in UNLV’s class of 2016 were placed in remedial classes, while the rate has risen to 79 percent at Nevada State College since 2013. Among Clark County high schools, Desert Pines High School had one of the highest rates of remediation, with 89 percent of students from the 2017 class requiring at least one remedial class at NSHE schools. Countywide the average was 53 percent.

Low-income students, students from low-performing high schools and black and Hispanic students are disproportionately represented in remedial education. Among Nevada’s 2017 graduates, 72 percent of African-American students were placed into remediation, compared with 43 percent of their white peers.

Corequisite classes

The goal is to do away with all remedial education, Reilly said, so that students enroll in a college-level course right away.

At UNLV, the first corequisite math classes will roll out in the fall, according to vice provost of undergraduate education Laurel Pritchard. Students who otherwise would have been in a remedial math class can opt for college-level algebra or precalculus instead, paired with a 2-credit corequisite section that will focus on reinforcing concepts, review and support.

“Students who start in remedial math progress very slowly,” Pritchard said. “It’s really unlikely that they will make it through all of the math they need.”

Pritchard said that while corequisite classes and Math Bridge share similar goals, they might appeal to different types of students. Fine Arts students, whose schedules are often jam-packed with travel or individual music lessons in the fall, may prefer a summer course, while other students could benefit from the extra help offered in a corequisite section during the regular school year, Pritchard said.

In other parts of the country corequisite classes have been shown to triple pass rates, according to Vanessa Keadle, senior strategy director of Complete College America, an organization working in Southern Nevada to improve degree attainment. That’s partly due to the demoralization students may feel in a remedial class.

“We are inviting students into our institutions, then telling them they don’t belong, that they aren’t prepared. It greatly affects students’ confidence, motivation and overall mindset,” Keadle said.

Math is the focus of the corequisite model because UNLV and other campuses have another approach to English that divides English 101 into a two-semester class known as a stretch course. At UNLV, students enrolled in so-called stretch English actually complete a college-level English course at higher rates than their peers who take a traditional single-semester English class.

B’anca Gibson, an incoming freshman enrolled in Math Bridge, said she knew she would be placed into a remedial course after she received her math scores via the ALEKS assessment in high school. She said she wasn’t too bad at math, but needed to work harder at it, and wished her teachers had spent more time teaching concepts.

She said she sees the benefit to a corequisite class.

“It’s not about how long it takes you to struggle, but what you learn in the struggle,” Gibson said. “Just because someone gets it faster than you, doesn’t mean you won’t get it.”

Contact Aleksandra Appleton at 702-383-0218 or aappleton@reviewjournal.com. Follow @aleksappleton on Twitter.